Robert Kolker

Robert Kolker

Doubleday ($25.95)

by Grace Utomo

Nine-year-old Mary Galvin wants to kill Donald so he’ll stop praying to her. It would be easy enough, especially since he thinks she’s the “sacred Virgin.” All she has to do is tie him to a tree and set him on fire. But she doesn’t. She knows if she does anything to her twenty-eight-year-old brother she’ll only prove that she’s crazy, just like him. Five decades and one name change later, Lindsay still hasn’t escaped Donald, but now something is different. Now she stays close to him by choice.

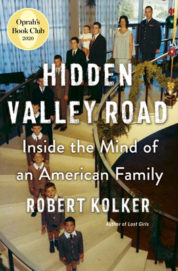

Robert Kolker's Hidden Valley Road envelops us in one of psychiatry’s least understood disorders: schizophrenia. The award-winning journalist centers his narrative on the Galvins, a family whose bizarrely high incidence of the disorder baffled scientists for decades. He begins by introducing us to Don and Mimi Galvin, optimistic newlyweds obsessed with creating the all-American family. Twelve children—ten sons followed by two daughters—seems a bit excessive by contemporary standards, but Mimi lived for motherhood and birth control was unthinkable for a Catholic couple in the 1950s.

The Galvins’ burgeoning household certainly appeared ideal to their friends in Colorado Springs. Don flourished as an instructor at the United States Air Force Academy, while Mimi excelled in local arts organizations and at home, even landing a headline in the Rocky Mountain News: SHE SERVES EXOTIC FOODS TO FAMILY OF NINE BOYS (complete with her recipe for lamb curry).

Of course, Kolker doesn’t just give us Don and Mimi’s version of their life on Hidden Valley Road; Mary/Lindsay (who changed her name to distance herself from her traumatic past) is his primary source for much of the book, and she tells a different story. Donald, the oldest Galvin, began beating up his younger brothers when he was a teenager. His perfectionist parents—intent on maintaining their public image—chalked it up to teenage angst since Donald behaved relatively well at school. As it became harder to disguise their family dysfunction when the next three boys grew violent, first at home and then in public, Mimi was determined to hide the truth about life on Hidden Valley Road, even when that precluded asking for help.

Her children were suffering from more than teenage angst. Donald experienced his first obvious psychotic break at CU Boulder, an episode that forecast his lifelong battle with schizophrenia. Kolker aptly describes the disorder as “walling oneself off from consciousness, first slowly and then all at once, until you are no longer accessing anything that others accept as real.” Five more brothers succumbed to alternative realities in the coming years: one was sexually aggressive; most were violent; all were delusional. Even the Galvins’ “healthy” children didn’t escape unscathed. Margaret and Mary/Lindsay were traumatized, not just by their brothers’ schizophrenic aggression but also by Mimi’s obsession with her sick sons.

Many journalists would pen a sensational tale of a stigmatized family and be satisfied with their work. Not Kolker. He understands that a real contribution to the schizophrenia narrative must extend beyond the shocking. First, it must humanize those society has called inhuman. Second, it must stimulate us to further dialogue.

Humanizing such an extraordinary story is a delicate business, especially when it comes to mental illness. It would be easy for the author to appear insincere—even with the best intentions—if they don’t have a prior personal connection to their topic. But Kolker circumnavigates this dilemma by letting the Galvins portray themselves. Mary/Lindsay is his primary speaker since she’s the Galvin brothers’ legal representative, but Margaret contributes diary entries, and Mimi gives an intriguing interview before her death in 2017. Lindsay’s analysis near the end of the book might startle readers the most, however:

So many people—including many of her well brothers—had stopped seeing Donald, Peter, and Matt as human beings a long time ago. . . . From her family, Lindsay could see how we all have an amazing ability to shape our own reality, regardless of the facts.

Even if we admit that many “normal” people stigmatize the mentally ill, we might not realize some of their loved ones do the same.

Kolker’s approach to depicting the Galvin family dovetails beautifully into portraying the scientific exploration of schizophrenia. From the moment Donald was diagnosed, Mimi faced the accusation that abusive mothers produced schizophrenic children. Once that theory was disproved and schizophrenia was suspected to be biological, scientists scrutinized the Galvins for a different reason. Who else could hold the key to the mysterious disorder, geneticists asked, but an entire family predisposed to the illness?

Sadly, all that research didn’t fast-track the Galvins to a cure. The brothers cycled through jails, mental facilities, and their home on Hidden Valley Road while psychiatrists pacified them with neuroleptic drugs—drugs whose side effects often grew worse than the disorder. Although Kolker narrates the history of general schizophrenia research as well as the brothers’ early treatments, he lets the Galvins’ avant-garde researchers speak for themselves. These personal interviews intensify their passion, their frustration, and their perspectives on what decades of testing the Galvin family actually accomplished.

What did their research accomplish? Kolker sprinkles his thoughts throughout the book but veils his final opinion until the final chapter, thus allowing us to draw our own conclusions. Like any good journalist, he supplies a plethora of angles: distraught parents, traumatized siblings, conflicted scientists, and even the central figures themselves (we get disjointed interviews with some of the brothers at the end of the book). Our opinions may be our own, but one thing is absolutely sure: People with schizophrenia are people, just like us.