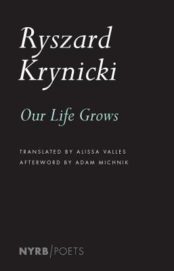

Our Life Grows

Ryszard Krynicki

Translated by Alissa Valles

New York Review Books ($14.95)

Magnetic Point: Selected Poems 1968-2014

Ryszard Krynicki

Translated by Clare Cavanagh

New Directions ($18.95)

by John Bradley

Zbigniew Herbert, Czesław Miłosz, Tadeusz Różewicz, Wisława Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski. To the list of great Polish modern poets, another name must be added: Ryszard Krynicki. Two new publications of his work firmly establish his importance.

Krynicki was born in a Nazi labor camp near Vienna in 1943. He grew up in a Poland “poisoned and paralyzed by political repression, economic corruption, censorship of the press and the arts, and state-sponsored campaigns against Jews and intellectuals,” translator Alissa Valles tells us in the introduction to Our Life Grows. As a young poet, he was one of the leaders of the “Generation of ’68” or “New Wave” of Polish poets who dared to speak out against the official lies. His work was censored and eventually banned; for a time, his name could not appear in print in Poland. Our Life Grows was published in Paris in 1977; the present New York Review Books volume also includes And We Really Didn’t Know (Early Poems).

Krynicki was born in a Nazi labor camp near Vienna in 1943. He grew up in a Poland “poisoned and paralyzed by political repression, economic corruption, censorship of the press and the arts, and state-sponsored campaigns against Jews and intellectuals,” translator Alissa Valles tells us in the introduction to Our Life Grows. As a young poet, he was one of the leaders of the “Generation of ’68” or “New Wave” of Polish poets who dared to speak out against the official lies. His work was censored and eventually banned; for a time, his name could not appear in print in Poland. Our Life Grows was published in Paris in 1977; the present New York Review Books volume also includes And We Really Didn’t Know (Early Poems).

These early poems show a fearless poet boldly confronting official propaganda, “the manifold lie, that everything could be erased, / that you could forget it all / and pretend nothing had happened.” Krynicki’s dark humor often appears even in the early poems, as can be seen in passages concerning “Nikita / Kruschchev’s posthumous / state of health,” and observations such as “the longer the speeches lasted—the longer the bread lines / got.” Yet we see a striking concision in the later poems of Our Life Grows. Take “My Daughter Learns to Read,” here in its entirety:

My little daughter, faultless until now,

is learning to read and write

and only now does she begin to errand I live my old errors of humanity

all over again.

Kyrnicki uses an oxymoron in his poem “My Beloved,” a phrase that describes his work well: “intimate distance.” This “intimate distance” allows him to feel great compassion for those manipulated by a repressive political system, and the anger to expose it: “human evil, / capable of everything, / prepared for anything, / is infinite, / and more inhuman / then we can possibly imagine.” Imagination harnessed as a tool of resistance serves as the main source of sustenance in these poems, as can be seen in “O,” a poem dealing with optimism, or at least the form offered by the government:

you speak through the O,

you spy through the O,

you listen in through the O,

you satisfy the intimate needs of the O,

falling asleep with a fat O in your mouth

Krysinski’s dark humor once again surfaces, his pessimism seen sprouting from the second letter of the word “optimism”—which generates, what else, "pessimism."

Magnetic Point, the New Directions volume, casts a wider net than Our Life Grows, as it includes poems from 1969 to 2014. In her informative introduction, translator Clare Cavanagh notes Krynicki’s “compression, mysticism, [and] wit.” To that list should be added his bittersweet empathy, as can be seen in the short poem “How to Write?”:

Magnetic Point, the New Directions volume, casts a wider net than Our Life Grows, as it includes poems from 1969 to 2014. In her informative introduction, translator Clare Cavanagh notes Krynicki’s “compression, mysticism, [and] wit.” To that list should be added his bittersweet empathy, as can be seen in the short poem “How to Write?”:

To write so that a hungry man

might think it's bread?First feed the hungry man,

then write so that his hunger

won’t go in vain.

Here, in five lines, is the author’s ars poetica. Writing has an important role, Krynicki believes, but there is a more essential priority, and once this has been satisfied, poetry may well threaten those in power. “How to Write?” clearly reveals why Polish authorities during the Cold War feared and censored this poet.

The last book from which Magnetic Point selects poems is Haiku from Last Winter (2009-2010), and it comes as no surprise to see Krynicki, always a lover of concision, embrace haiku. Like Issa, Krynicki often takes note of insects:

In today’s mailbox

alongside ads and bills:

a shrinking spider.

Because both the NYRB and New Direction volumes offer translations from Our Life Grows, the reader often has a chance to compare versions of the same poem. Here’s the opening of the title poem as translated by Alissa Valles:

Our life grows like astonishment and dread

forgotten for a moment in a lover’s arms,

our life grows like a line for bread

Here are the same opening lines, as translated by Clare Cavanagh:

Our life grows like fear and panic,

our life grows like bread lines

The compression of the Cavanagh translation aptly suits Krynicki’s style, but it does leave the reader wondering about that second line in the Valles translation. Did Cavanagh drop it? Did Valles invent it? Elsewhere in the same poem, Cavanagh’s translation proves to contain more bite; where Valles offers “our life grows like a fruit and like hunger,” Cavanagh is blunter: “our life grows like a fetus, like famine.”

While Magnetic Point provides the better overview of Krynicki’s poetry, readers are fortunate to have both volumes of this poet, who speaks to our own time. It may sound odd to say this about a Cold War survivor, but consider this excerpt from “Truth?” with its questions many Americans are now asking:

What is the truth?

Where are its headquarters?

Where is its board of directors?

Where is its legal team?

Where are its bodyguards?

Where is its PR division?

Where is its marketing?

Who are its overseers?

Who handles follow-up?

Who are its media sponsors?

Don’t be surprised if one day soon Ryszard Krynicki joins Czesław Miłosz and Wisława Szymborska in winning the Nobel Prize for Literature.