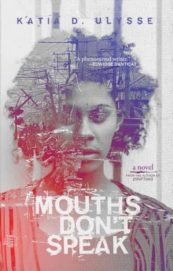

Katia D. Ulysse

Katia D. Ulysse

Akashic Books ($15.95)

by Julia Stein

Katia D. Ulysse’s powerful first novel Mouths Don’t Speak explores suffering, both physical and emotional, and one woman’s search for closure. The Haitian protagonist Jacqueline lives in Baltimore and struggles with deep psychological wounds inflicted by her mother, who still lives in Port-au-Prince. The novel challenges stereotypes of Haiti—extreme poverty, unstable communities, etc.—by capturing the lives of its wealthier residents: Jacqueline’s parents, Annette and Paul, had two luxury department stores and were friends with the President, but Annette dumped their daughter in a U.S. boarding school, abandoning her for years. In the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, however, Jacqueline is driven by guilt and grief to travel back to the country she left as a child twenty-five years prior.

The novel’s title comes from Psalm 135; 15-18: “The idols of the nations are silver and gold, made by human hands. They have mouths, but cannot speak.” Ulysse criticizes those humans who gorge on silver and gold like Annette, while managing to capture another aspect of Haitian culture: its deep religiousness. As a young woman, Jacqueline found sanctuary in regularly attending church and drew inspiration from the pastor Sister Marsha, who vowed to be the loud voice “for those who can’t or are too scared to speak for themselves. Mouths don’t speak, they say, but I refuse to keep the secrets of evildoers!”

Ulysse creates strong, believable characters—starting with the callous Annette, who thinks her estate should be a fort protecting her from “democracy seekers.” Many characters have deep wounds: Annette’s husband Paul, crippled in the 2010 earthquake, is kind but ineffectual in his protests to his wife; Jeanette, an art teacher, mother, and wife, is still angry at how she was abandoned as a child; Jeanette’s husband Kevin has PTSD from fighting in U.S. wars. In Baltimore, Jacqueline suffers when watching the 2010 earthquake destruction from afar but then decides to study Haitian Creole as a way of reconnecting with the culture. At first she is shocked that her teacher Leyla is a blue-eyed, very blonde American, but soon learns that this blonde spent twenty years in Haiti doing research and also worked helping penniless rice farmers begin other businesses, saying, “How can you make a living when the country is littered with cheap rice from the good old US of A?” In Mouths Don’t Speak, what counts are one’s actions and words.

In the second half of the novel, Ulysse describes at-length how characters struggle to heal from their traumas. After the earthquake, Jacqueline finds healing through studying Creole and learning how to dance to vodou jazz—a loud, angry, and political music—while impoverished Haitians start a new bazaar with market stalls near her parents’ house. Annette and Paul have an estate full of fruit and breadfruit trees they rarely eat, but now the hungry poor “just slipped through the holes in the wall and harvested a few.” In one sense, the hero of the novel is really Annette and Paul’s groundskeeper Pachou, who has worked for Annette for sixty years; readers will cheer as he stands his ground and demands his rights. In this fascinating novel about Haitian life, Ulysse beautifully braids together the struggle for personal redemption with the struggle for dignity and human rights.