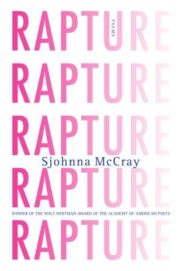

Sjohnna McCray

Sjohnna McCray

Graywolf Press ($16)

by Renoir Gaither

Sjohnna McCray’s debut collection of poems makes obvious the import of Faulkner’s famous aphorism, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Winner of the Walt Whitman Award from the Academy of American Poets, Rapture is an absorbing homage to McCray’s growing up as a biracial child of an African American father and Korean mother in the 1970s and ’80s, and it also sifts through various impressions of midlife identity as a gay man. The result is soulful, solemn soul-baring that leaves us changed by its wisdom.

In the opening poem, “Father & Son by Window,” McCray uses a second person narrative voice to paint an intimate scene of a son bathing his infirm father:

Tonight, you flip the night

as if it were a card.

You scrub his back,move briskly through the arms.

You match the constellationseach to a different longing.

So light you’re hefting nothing.

The poem ends with an unassuming yet surprising metaphor, as tight and redolent as a shuttered church:

You follow the knots, the dark scars

on a face turned away from water.

His memory flickers on—a light from a porch nearby.

McCray’s metaphors and similes create natural oases in the narrative ecosystem he renders. In the poem “Three Ways to Scat about a Leg & a Father,” these oases well up in disparate registers and sentiment:

Tonight, the fog rolls like slow music,

the moon is a monster under sheets.

The band of guardian angels

Hanging outside the window jive,

“Man, that cat is square.”

Such verbal derring-do can also shift to brutal honesty. In “Comfort Woman,” McCray reimagines his Korean mother’s experience as a sex worker during the Vietnam War. South Korea’s military established a string of comfort houses during the war to which it sent some 300,000 troops:

This is something my mother knew: to fuck

a man without a metaphor, without

even the slightest hint of a story,

is to be at the center of two deaths.

To see with her eyes is to see as

a camera lens stripped of gauze:

the unwelcome influx of light

reducing men to texture:

Here we encounter a speaker who maintains a bitter emotional distance, ringing out what’s essential and emancipating with an acute sensitivity that’s ultimately gratifying. In another example, the wickedly clever poem titled “Puberty in a Jar,” two boys catch salamanders beside a stream; the enterprise operates, of course, as a larger metaphor for desire and its all-too-often elusive objects. During a feverish attempt to capture an amphibian, the speaker’s companion submerges his jar in the water:

Glass breaks against the rocks.

Held in the sun, his hand

is dazzling covered in bits

of shards and mud. Bloodstreaks through the creek

the color of cherries,

a lustful blush

that soon disappears.

The poem summons elements of myth—shared experience, sense of belonging, and ritual—as do others in this amazing collection. McCray shepherds us through this fluid and evolving project of discovering identity with compassion and grace.