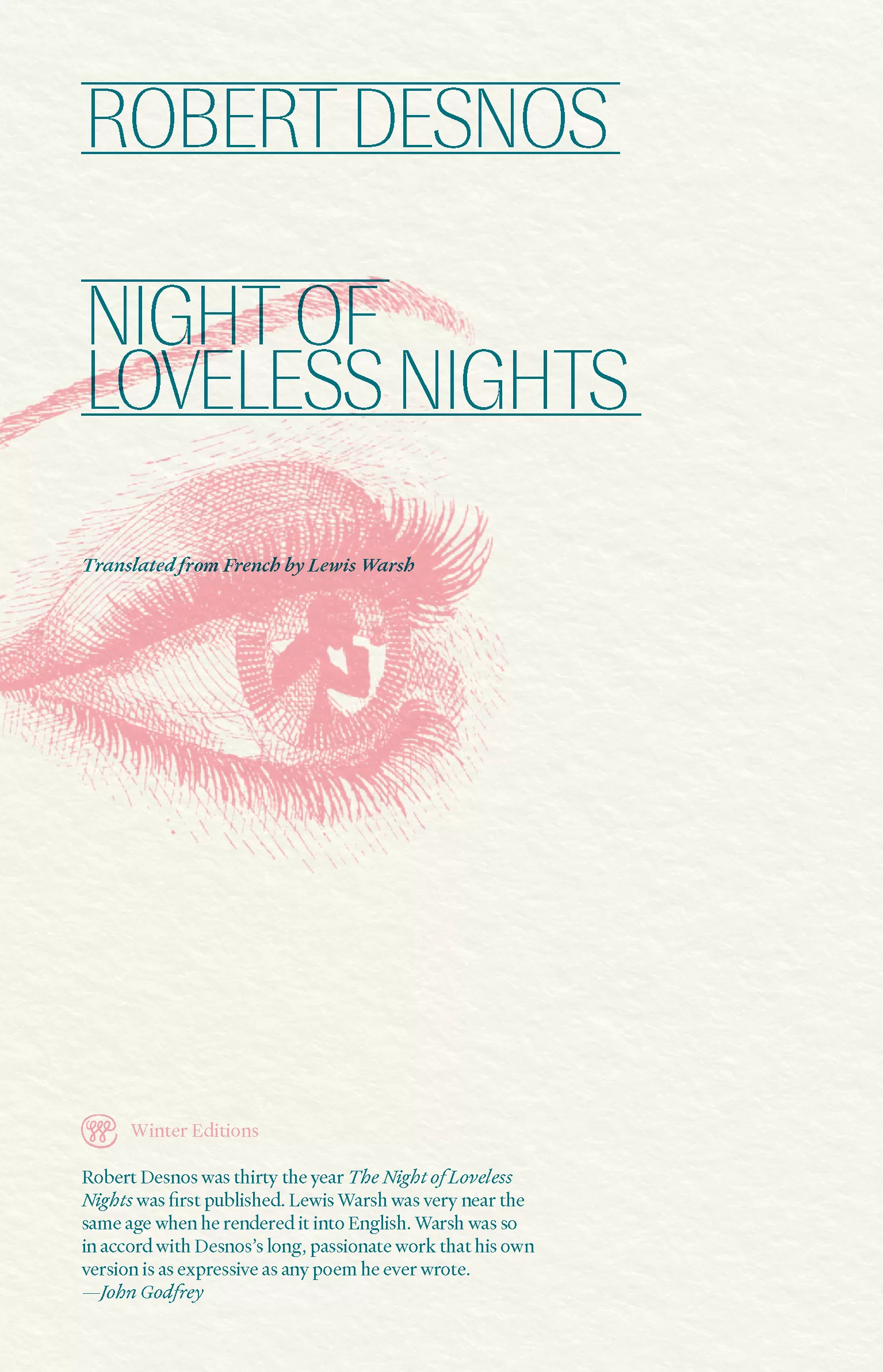

Robert Desnos

Translated by Lewis Warsh

Winter Editions ($20)

In 1922, the Surrealist prodigy Robert Desnos (1900-1945) threatened his friend and fellow poet Paul Eluard with a knife while speak-walking and sleepwalking, singing under hypnosis or in dreams. Though Surrealism’s dream kingdom has been watered down here in the U.S. to advertising, in his 1929 poem Night of Loveless Nights, Desnos imbued love, death, and jouissance, the “little death,” with that tragic magic of his signature themes. A new edition of this truant poem marks the 50th anniversary of its translation into English by New York School poet Lewis Warsh (1944-2022).

Through an epic drift of shifting moods, motifs, and styles, Desnos constrains or expands Surrealist automatism to include the alexandrine, one of the strictest self-conscious classical meters in rhyme. It’s a form close to prose, at which Desnos excelled; he notoriously composed lengthy automatic prose poems such as Liberty or Love! as well as the deftly opiated novel The Die Is Cast. In Night of Loveless Nights, Desnos splits the difference, displaying endearingly enduring twelve-beat rhyme amidst idyllic lyric while breezily tossing off kiss n’ tell bagatelles in a single languorous love song or run-on billet doux.

Unlike its appearance in the ’70s, the original French text of Night of Loveless Nights is included in this new edition, but if it reveals that some of Warsh’s version seems forced, it’s not from oversight or ineptitude, but rather from compelling the strictest of regimes to meet its own demands. Following Desnos, Warsh teaches rigorous classical verse to lilt, laugh, and utter nonsense (“utter” here being both superlative and verb). Reachy malapropisms arc from the recondite and recherché to the heteroclite and Byzantine:

Like the clouds evening parties are born without reason and

die with this tattoo on top of the left breast: Tomorrow

In its first manifesto, Surrealism stuck to avant-garde schemes without glimpsing lateral or equal dispersion strategies to come. Desnos’s reply to the position he inherited as Surrealist seer was to outdo even his fellow enragées:

One day I met the vulture and the sea hawk.

Their shadows on the sun did not surprise me.

Much later I made out the chalk on the ramparts

The carbon initial of a name I knew.

In its second manifesto, André Breton excommunicated Desnos for essaying rhyme and fairy tales; acting after that as a sleeper agent, Desnos is perhaps the more adored of the two today. His death at a Nazi concentration camp in 1945 makes it all the more important that readers revisit him today, with fascism alive and smelling rank in the age of its technical reproduction.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2024 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2024