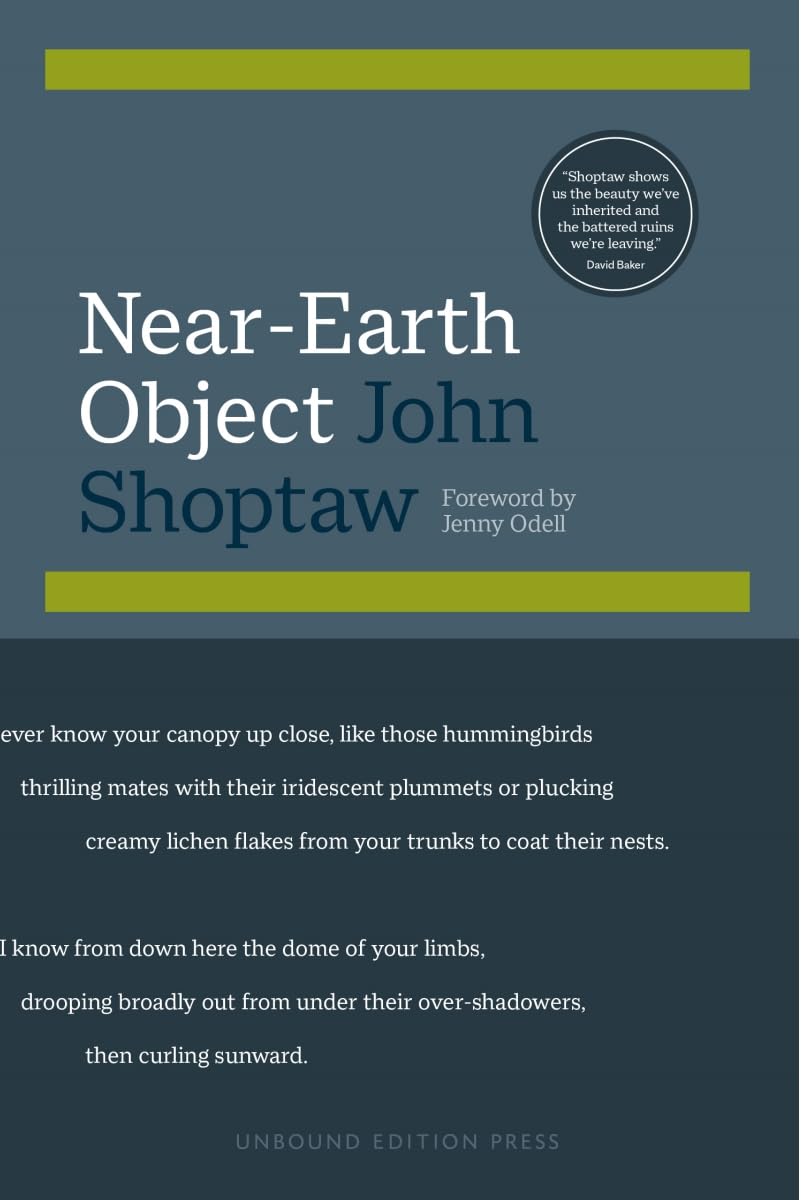

John Shoptaw

Unbound Edition Press ($25)

by Lee Rossi

Poetry can be personal, but as T. S. Eliot famously insisted, it can also be impersonal. Can it ever be both at once? In his latest collection, Near-Earth Object, John Shoptaw mixes disparate elements—formal and informal, autobiographical and traditional, and, yes, personal and impersonal—creating a work that takes various paths to express the existential crisis of our time: the effects of climate change.

From the outset, Shoptaw offers a guided tour of various disasters and disaster zones: the asteroid Chicxulub, clear-cut forests, the North Pacific Gyre, climate refugees, desertification in the Sahel. It’s not pretty. “Dry Song,” which beautifully reworks some of the basic motifs of Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” reveals the terrifying reality of salmon unable to reach (or leave) their spawning beds because streams are running dry:

But the drought has pierced to the mountain route

and shown me rock under the shrunken mantle

and sand it fed to the river mouths, barring

salmon on their redds from salmon in the sea.

“Back Here” takes the tack of using the patois of “Swampeast” (southeast Missouri), Shoptaw’s boyhood home. “We believe in everything life has given us,” the speaker says—the few good things, the many disappointments. “We believe in you,” he tells the prodigal poet, but goes on to say, “Honestly, we don’t know what to believe. / We don’t believe you do either.” Finally, though, the speaker admits: “We know. The earth is dying. We get that. / . . . / Naturally, we’ll do what we can. / Only please don’t ask us / to change our climate for yours.”

Employing skewed formalisms in many of the poems, Shoptaw emphasizes that resilience and creation are as much a part of our behavioral repertoire as violence and despoliation. He craftily leans into the little-used “Poulter’s Measure” (a popular Renaissance meter) for an antic anecdote about the fried chicken of his youth. The poem begins with memories of a visit to a boyhood chum:

We play with our trucks out back in the dirt, where plump

red hens peck for bugs but keep clear of the hackberry stump.

Then checkers on linoleum in the kitchen

where Chuck’s mom in a red housedress turns: Cornflake fried chicken?

The music is charming, but there are deeper currents. Comparing himself to his friend, the speaker notes:

I grew on the wrong side of the rails but the right

side of the river in Missouri, Chuck on the wrong side

of both.

Shoptaw also likes large canvases; the final sequence in the book, “Whoa!,” revisits the myth of Phaeton in light of the environmental woe already upon us. Throughout the work’s twelve parts, Shoptaw offers many of the traditional pleasures of the long narrative poem, among them learned lists (flowers, decaying glaciers, unrepentant polluters), elaborate similes, and inflated rhetoric. Shoptaw’s list of “wide-waking annuals and perennials,” for example, is as specific and delightful as Milton’s famed list of flowers in “Lycidas” without dispelling the somber and elegiac tone of the whole:

snowdrops, crocuses, daisies and daylilies,

rice in flower and maize in silk,

woozy jasmine and heady grapevines . . .

Of course, all these pleasures are in service to a larger design. As our modern-day Phaeton (here cleverly named “Ray”) courses recklessly, he disturbs the jet stream and sends untimely cold snaps on New England and New York, causing disaster around the globe:

Coulters

and ponderosas, yellowed and browned, engraved

with trilobite grooves by pine-bark beetles

wintering northward, had turned from trees

into tinder.

Notice how Shoptaw’s four-beat lines evoke but don’t slavishly imitate Old English accentual verse, the alliteration deployed almost casually to reinforce the drive of the narrative.

Ray, it might be noted, is clueless, but at least he has the excuse of youth and inexperience. Not so “the fossil lordlings / . . . out / sledding with their kids in Central Park”; “Where’s the heat?” they want to know, their cluelessness a testament to their motivated ignorance. Since this is a mock epic, retribution is called for, so in Shoptaw’s telling, Earth herself fires a lightning bolt at Mister High and Mighty, ejecting him from “his plump white boy’s life.”

What Shoptaw offers readers, then, is not an answer but a fantasy of reprisal, one with no more impact on social policy than the tagging of a freeway overpass has. Perhaps that’s what most writers do—scrawl texts in hopes it might shock us into saving ourselves from tragedy. Few, however, do it with the force and elegance of Shoptaw.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025