by Leverett T. Smith, Jr.

by Leverett T. Smith, Jr.

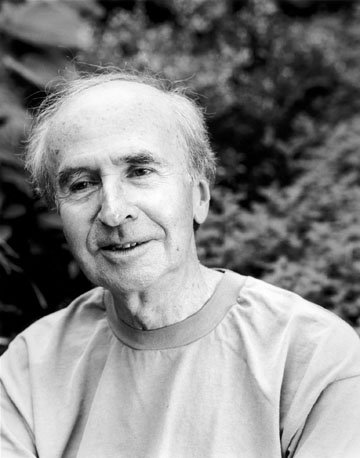

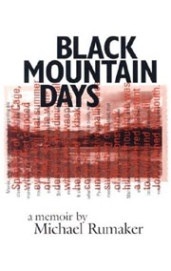

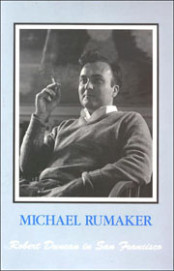

As he relates in his 2003 memoir Black Mountain Days, Michael Rumaker studied writing and much else with Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and others at the legendary Black Mountain College; the memoir amply captures the feeling of being at the experimental college in the 1950s and brings to life the various people who lived and worked there. Clearly Rumaker honed his craft and his sense of character at Black Mountain: His stories concerning drifters and other outsiders were first published in Black Mountain Review while he was still a student at the college, and were later gathered in Gringos and Other Stories, published by Grove Press in 1967; a novel about mental illness and recovery, The Butterfly, also appeared in the 1960s from Scribner. Beginning in the 1970s, Rumaker began publishing memoirs and poems as well as fiction, most often using a first-person narrator; his principal subject became gay life in the novels A Day and A Night at the Baths and My First Satyrnalia, the memoir Robert Duncan in San Francisco, and the poem “The Fairies Are Dancing All Over the World,” which is included in the 2005 release Pizza: Selected Poems. Later novels expanded the scope of his themes, such as the 1992 novel To Kill a Cardinal, a thriller in which various sexual outsiders demonstrate against the Catholic Church in New York City, and the 1999 novel Pagan Days, a well-wrought investigation into the nature of childhood narrated by an eight-year-old boy. In all his work, Rumaker demonstrates a keen ear for mellifluous language and an affinity for narrative clarity, yet at the same time he seeks to excavate what lies beneath the surface, believing that “the unconscious nests the actual,” as he puts it in his essay “The Use of the Unconscious in Writing.” In the following interview we discuss his long career in the world of letters, from his “Black Mountain Days” to today.

Leverett Smith: Politics is in the air at the moment. How does it manifest itself in your writing?

Michael Rumaker: There has always been in American writing, unlike in other cultures, the insistent argument that so-called creative or literary writing must be free of the political. How, then, to get it in? Preachy and teachy harangues quickly grow old, but the political—by which I mean real human lives not abstractions as so much politics is today—has always been a vital aspect of our daily lives. Is it possible to get the political into our words, that long and lively tongue of language through the ages, the tongue that knows that words are tasty in the mouth? I can cite several of my own works, including the poem “The Fairies Are Dancing All Over the World” (the political as humor); the novel To Kill a Cardinal (the political as satire); and another novel, A Day and a Night at the Baths (the political as open celebration of male-on-male sexuality after centuries in the shadows).

The question is, where is the common ground we need to get to, beyond ego, beyond ambition, to reach the floods of alluvial strata of eons of past lived life, animal and human, that are deposits in each of us, in the dark reaches of mind and spirit, in the unconscious at the back of our brains? Such ancient strata are in our every movement, every gesture, in the dance of hands, our first language, in the same hands that now hold a pen or tap the keyboard of a computer; strata that any writer worthy of that name digs to unearth, as poet Charles Olson did, simultaneously in living self and in the world around us, in language equally alive if we are alive.

So much human experience slips back underground, hence the importance first of knowing who we are, then of telling, of writing, getting it down, getting it right. Important to dredge up what has been buried yet remains simmering in one’s own time, the suppressions and oppressions, the brutal injustices, the silences; necessary, once that ground has been raked, to shout it out loud, to be heard through centuries of the silt of deafness and forgetfulness. Memory unearthed is our genius. But once it’s brought to the surface, once it’s heard, it becomes important then to move beyond the purely political, beyond identity politics of race and gender, of sexual orientation, to get to the core complexities and contradictions, the personal and impersonal of that ground we share, no matter where, of what it is to be human; to uncover the dynamic spirit and energy of the archetypal vertical male and horizontal female in each of us, the core, where they meet—“the vectors of force” Olson told me I needed to discover (uncover) during the summer of 1955 in my study at Black Mountain, just before my graduation. Like the dance of the hands as first language, these primal views root our conjoined perspectives for life continuing.

LS: You’re describing the political as something “buried,” “forgotten, hidden away.” I’m immediately reminded of Henry Thoreau’s instructions in Walden: “Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion, and appearances, that alluvium which covers the globe, through Paris, and London, through New York and Boston and Concord, through Church and State, through poetry and philosophy and religion, till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we can call REALITY, and say, This is, and no mistake, and then begin . . .” I think, too, of your story “The Pipe,” a powerful, mysterious tale in which all sorts of stuff is dredged up. And the phrase “Memory unearthed is our genius” is quite striking. Can you elaborate?

MR: William Carlos Williams said “Genius is memory,” that we can remember backwards to rock-bottom and then begin to go forward, to start from scratch, cleansed of the accumulated detritus of the past, as Thoreau suggests. That we can do this as no other living species can is our genius.

I wasn’t familiar with Thoreau’s passage, having read the book half a century ago at Black Mountain College, and it surprised me in its similar train of thought, even similar to some of the language as my own. Thoreau’s gnarled, insightful thought sums up with beautiful succinctness what we need to do—the process of heading to the bottom. Robert Duncan said, “When in doubt, go to the bottom.” And I agree wholeheartedly. In writing, in any art, dive for the bedrock, the primal, the unencumbered origins.

LS: Beginning in the mid ’70s, your writing—poetry, fiction, and memoir—appears to change quite radically, in tone, in voice, in content. What discontinuities do you see in your writing from the ’60s?

MR: My presence. In those early stories from the 1950s, my presence was stripped from those lean narratives; the “I” was “hidden,” “buried,” as you cite, the “I” had been a hard, cold, unflinching eye, without sentiment. With the upheaval of the late 1960s and the advent of gay and lesbian liberation, and after my recovery from my struggle with booze and drugs, I felt the strong drive to speak up and speak out. I began to use the first person singular in my writing, with no more use of third person “Jims,” as in The Butterfly and “The Desert.” Looking back, that did have everything to do with “defining,” to use Toni Morrison’s fine statement regarding definition from Beloved: “Definitions belong to the definers—not the defined.”

To the old saw “Know thyself” we might add “Define thyself,” lest others do it for us, to our detriment and peril. It was time for me, and for many thousands of others then too, to stop letting others define us—in religion, in law, in education, in psychology—and begin to define ourselves, in our own words, through our own experience, our own lives; to begin to shed the choking skins of centuries of hatred and ignorance, of murder and execution, of imprisonment in both penitentiaries and mental institutions. It was time for us to free ourselves from the stereotypes, myths, and abstractions of others defining from a distance who we are in order to maintain their own power and privilege, their control, at our expense, those who “cost others at no cost to themselves.” As Elie Wiesel said to Reagan, “Evil is the inability to imagine the lives of others.” Again, “know thyself,” but also “define thyself.” I was certainly ready to begin practicing the latter, which was most evident in those memoirs-as-novels I wrote in the 1970s, My First Saytrnalia and A Day and a Night at the Baths, and in the poem “The Fairies Are Dancing All Over the World.”

To the old saw “Know thyself” we might add “Define thyself,” lest others do it for us, to our detriment and peril. It was time for me, and for many thousands of others then too, to stop letting others define us—in religion, in law, in education, in psychology—and begin to define ourselves, in our own words, through our own experience, our own lives; to begin to shed the choking skins of centuries of hatred and ignorance, of murder and execution, of imprisonment in both penitentiaries and mental institutions. It was time for us to free ourselves from the stereotypes, myths, and abstractions of others defining from a distance who we are in order to maintain their own power and privilege, their control, at our expense, those who “cost others at no cost to themselves.” As Elie Wiesel said to Reagan, “Evil is the inability to imagine the lives of others.” Again, “know thyself,” but also “define thyself.” I was certainly ready to begin practicing the latter, which was most evident in those memoirs-as-novels I wrote in the 1970s, My First Saytrnalia and A Day and a Night at the Baths, and in the poem “The Fairies Are Dancing All Over the World.”

LS: The new magazine Process will publish your play Queers soon—its first publication in English since you wrote it in 1969. What caused you to turn to drama? Has the play ever been performed? In writing it, are you still “heading to the bottom”?

MR: Though encouraged to try our hand at anything available to us at Black Mountain College, my first attempt at writing a play was a disaster. In theater instructor Wes Huss’ class, I had the idea to transpose Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor chapter in The Brothers Karamazov into a one-act drama. The total put-down for my innocence that evening, which I relate in Black Mountain Days, sure made me play-shy.

Even so, after Black Mountain, I tried again, when I decided to make my short story “The Desert” into a play, which the Actors Studio in Manhattan in the 1960s agreed to put on as a workshop production. But that, perhaps mercifully, never panned out when the director got called away on another project. The play was then taken up by an independent young director with no ties to Actors Studio, who turned out to be psychotic; he ended up tearing the manuscript of my play to bits in a furious rage, then hurling the blizzard of scraps in my face, screaming, “You’re a homosexual! You’re a homosexual!”—which in those dark, homophobic days was akin to calling someone a serial killer. By that time, I saw plainly I better stick to narrative prose.

Still, a few years later, following the explosion of the Stonewall Rebellion in June of 1969, a rebellion heard literally around the world in a very short time, I tried my hand at Queers, this time driven by an urgent necessity to exorcise the demons of strife with my family as well as my own deeply internalized homophobia (the terrifying young psychotic director earlier turned out to be one of those negative “helpers” in a way). Putting it in play form struck me as the only way to do it, dealing with themes that were deeply rooted in the unconscious, and the fit setting for it a New York City subway station, the underground system then having public toilets that were smelly, notorious and dangerous places for furtive male-on-male sex. The saying “We are as sick as our secrets” was another reason I knew I needed to attempt to deal with those secrets, starting within myself and then with my own flesh and blood, a cleansing ritual of all the inner shame and flesh hatred, as fallen Catholic and as a criminal in the eyes of a society whose laws made such furtive acts of pleasure a crime.

As I said in your Black Mountain College Dossier Eroticizing the Nation: Michael Rumaker’s Fiction, “Writing Queers, nearing the end of my boozing and drugging, was like lancing a boil.” That in a time when so much of my life was, as were the lives of so many others, “buried,” that word you earlier cited rearing its head again. It makes me think of what I heard a fellow mental patient say on one of the locked wards at Rockland State Hospital years ago: “The unconscious, that’s where the wrecks are.” Hence, the emblematic Manhattan subway setting for Queers. Plus, as I also said in Eroticizing the Nation, “Thinking back on it now, it’s really a family play, in the most ironic sense, deeply autobiographical; a takeoff in a way of LeRoi Jones’s contemporary play Dutchman, which also is set in a Manhattan subway, and dramatizes black male rage against whites, as Queers dramatizes a cast-out son’s fury and despair over deeply entrenched parental and societal homohatred.”

Yes, a young couple out of Gloucester, Massachusetts, Lisa and David Rich, is bringing out a new magazine, Process: a literary journal, whose main aim is to recover and uncover writers who have been forgotten, marginalized, or unheard in our already linguistically benighted nation. They will publish the last half of Queers. When I wrote it back in 1969, my agent at Harold Ober Associates in New York, Patricia Powell, tried her best to get it published here in America, but no one would touch it, and there was no possibility for a production either. Finally, in 1970, Ober’s agent in Zurich got it published in a German translation with the title Schwul, by Marz Verlag, a cutting-edge press in Frankfurt. (In 2004 Marz reprinted Schwul in a volume with Irving Rosenthal’s classic novel of the same period, Sheeper—Schops, its German title.) As far as I know, Queers has had a handful of productions overseas—the first soon after I wrote it, by an avant-garde group in London called the Gay Sweatshop, and a couple other times in its German translation in Germany, I believe. There was another production as recently as the 1990s in the Netherlands.

Yes, a young couple out of Gloucester, Massachusetts, Lisa and David Rich, is bringing out a new magazine, Process: a literary journal, whose main aim is to recover and uncover writers who have been forgotten, marginalized, or unheard in our already linguistically benighted nation. They will publish the last half of Queers. When I wrote it back in 1969, my agent at Harold Ober Associates in New York, Patricia Powell, tried her best to get it published here in America, but no one would touch it, and there was no possibility for a production either. Finally, in 1970, Ober’s agent in Zurich got it published in a German translation with the title Schwul, by Marz Verlag, a cutting-edge press in Frankfurt. (In 2004 Marz reprinted Schwul in a volume with Irving Rosenthal’s classic novel of the same period, Sheeper—Schops, its German title.) As far as I know, Queers has had a handful of productions overseas—the first soon after I wrote it, by an avant-garde group in London called the Gay Sweatshop, and a couple other times in its German translation in Germany, I believe. There was another production as recently as the 1990s in the Netherlands.

I was of course apprehensive about the publishing of a play, if only its latter half, that I’d written almost 40 years ago. I figured its only interest might be for psychological and historical reasons, a graphic portrait of yet another benighted time in America. I was so doubtful, I didn’t even have the nerve to re-read it and quickly walked it to the post office before I changed my mind. But the Riches thought otherwise, Lisa emailing me, “we finished Queers, reading it aloud to one another. I read it through again after that. It is impressive. Brutal and tender, still raw, still controversial. I’m not surprised that few in the US have had the balls to stage it. We will certainly excerpt part of it for the magazine, probably the last section, from p 31 or so to the end. It is stunning. Thank you.”

I sure was pleased, and relieved, to have the news, and even more pleased to know that at least the last half of Queers would at long last be published in its original English here in the USA. Lisa’s email gave me the nerve to finally sit down and re-read the play for the first time since I wrote it. Given that length of time it was so fresh to my eyes, it felt like I was reading the words of a stranger, someone I no longer knew: a rather pathetic, tormented and desperate young man. And I, too, was surprised at its rawness, at its graphic and even occasionally powerful language. A reminder perhaps of what was, and given the increasingly authoritarian and reactionary climate in these States today, may still be again.

You asked in concluding your question, “In writing it, are you still ‘heading to the bottom’?” I can only say, since I dwell in uncertainties, that in my writing I always find it necessary to head to the bottom, go to ground, diving for the primal, the beginnings, to find my footing, my directions.

LS: One thing I’m curious about—and this goes back to your answer to the third question—is how you got from the objective third-person narrator of your early stories to the involved first-person narrator of A Day and a Night at the Baths and My First Satyrnalia. Did writing the two memoirs in the early ’70s on Robert Duncan and Robert Creeley have anything to do with it?

MR: If art is a “subterfuge,” as D. H. Lawrence suggested in Studies in Classic American Literature, then I guess I’d gotten to the point where I was ready to let the mask slip, to show a more naked face in my writing. Conversely to Lawrence’s remark, addiction, too, is a subterfuge, a hiding from and cheating at life, and that subterfuge ended for me, thankfully, in June 1973. The closet, too, is a subterfuge, a denial of one’s identity and of one’s very humanity. Freedom from booze and drugs gave me not only the freedom and courage—and equally important the clearheadedness—to stop hiding behind the masks of those addictions, but also the nerve to begin to stand up and not only speak the truth of my life in a more open and truer voice, but also to put that down in my writing, using the more naked and vulnerable first person “I,” and no longer concealing myself behind the blind of the third person. Ezra Pound said, “You can’t cheat in writing.” A writer’s got first of all to be honest. If you’re hiding, if your life is buried beneath addiction and fear, honesty’s not possible, until you face up to that and change.

And, yes, that’s all reflected in works like “Robert Duncan in San Francisco” and “Robert Creeley at Black Mountain”; those writings were the impetus to get to A Day and a Night at the Baths in 1978 and My First Satyrnalia in 1980, the self finally as “bare forked root,” only presenting what is.

LS: The 2005 publication of Pizza: Selected Poems has reminded us that, though you’re known as a writer of fiction and memoir, you’ve all along been composing and publishing poems as well. How do they relate to your other work?

MR: Some prose works have started out as poems, such as A Day and a Night at the Baths and My First Satyrnalia, etc., but I’d seen pretty quickly that, because of their growing length and the increasing amount of detail, plus that the poems were actually taking the shape of autobiographical stories, they really needed to be prose works. However, just as with my futile stabs at play writing, I’ve never had much confidence in my rudimentary attempts at poetry, starting in Olson’s writing classes at Black Mountain where I was early pegged a prose writer, on up until recently when I was hesitant to give my okay to Circumstantial publisher Richard Connolly to print a selected few in Pizza. In much of the verse in that selection the narrative impulse is still strong, as in “Yet Another Poem Addressed to Walt Whitman” and “To a Motorcyclist Killed on Route 9W.” That’s probably what Creeley was driving at in his blurb on the back cover: “. . . old time evocations and reflections on a real life in hard real times.”

But a mighty overshadowing was deep-down knowing when one has been among poets such as Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, and Robert Duncan, to name a few, one feels to be a sapling among sequoias.

Still, there are several poems in Pizza that transcend narrative, whose reach moves in other directions, beyond the confines of telling, such as “The Fairies Are Dancing All Over the World.” There the shape of the poem shimmying down the page becomes a wavy, unbroken dance rooted in the rhythms of the poem, bouncing in a line like “May the fairies swivel his hips,” evidence that, free of the rigor mortis hell of booze and drugs, I could breathe again and my own hips began to swivel once more.

Or another poem such as “For Jeffrey Dahmer (murdered today in prison, 11/28/94),” Dahmer held as a throwback in the depths of self, at the terrifying rudimentary origins of love, which few of us ever have had the courage to look at in ourselves, or at the cannabilization, figuratively, in evolved love, how we eat each other up, as nature does. Colette said, “When the words I love you are spoken, blood is drawn.” Jeffrey Dahmer was, at bottom, a bottom feeder, if you will—a nightmarish throwback stuck in the origins of the muck of love. Dahmer, awe-struck, commands our awe.

Or another poem, “Boston Tea Party,” centered on aging and death, and also on John Wieners as invisible queer, invisible poet, like all poets marginalized to invisibility, or at best, like Olson, to merely “cult” status, in these increasingly deaf and blind times.

LS: You mentioned that your novels A Day and a Night at the Baths and My First Satyrnalia started out as poems. Why should they have begun that way? What else prompted you to write this sort of “autobiographical story in fictional terms”?

MR: I didn’t foresee the possible dimensions, and thought writing a poem about my first experiences at the Everard Baths or at my first Fairy Circle would do the trick. The stab at making those experiences poems was that first step into them as it turned out. I finally perceived the content needed to grow into story, its correct venue, its right form.

More to the point, getting back on my feet after getting sober, incapable as yet of tackling anything book length, I got back to writing again by writing shorter pieces, especially those long poems “The Fairies Are Dancing All Over the World,” “Pizza,” and “A Day at the Bike Races” and the prose pieces “Robert Duncan in San Francisco” and “Robert Creeley at Black Mountain.” In those first steps of my moving back out into the world again, such experiences as the ones at the baths and at the Fairy Circle first presented themselves as poems. But as my imagination returned, the content of those experiences began to take on a complexity of detail too unwieldy for a poem, and I’d reached the point in 1977 where I was able to muster up the nerve to attempt that first longer prose work—even if only a novella, as it turned out, of 8l pages, and which took me a year to write.

More to the point, getting back on my feet after getting sober, incapable as yet of tackling anything book length, I got back to writing again by writing shorter pieces, especially those long poems “The Fairies Are Dancing All Over the World,” “Pizza,” and “A Day at the Bike Races” and the prose pieces “Robert Duncan in San Francisco” and “Robert Creeley at Black Mountain.” In those first steps of my moving back out into the world again, such experiences as the ones at the baths and at the Fairy Circle first presented themselves as poems. But as my imagination returned, the content of those experiences began to take on a complexity of detail too unwieldy for a poem, and I’d reached the point in 1977 where I was able to muster up the nerve to attempt that first longer prose work—even if only a novella, as it turned out, of 8l pages, and which took me a year to write.

To backtrack a bit: in the writing classes at Black Mountain College, Olson spoke out against “the brief lyric.” He encouraged a substantive engagement in the poem, to strike out—or, as he also put it, “to leap in feet first,” and to do so without preconceived notions, to see where the rhythmical energies of breath, mind, ear and eye led us. And as for length, he always emphasized that a poem is as long as it has to be. It wasn’t the I Ching of John Cage, the random scattering of chance, anathema to Olson, but rather the form that would emerge from an intense transformative engagement with content, to paraphrase Creeley, by word and by image—image always a thorny question front and center with Olson.

I was ever mindful of that, and it wasn’t until after I left Black Mountain that I tried my hand at longer poems, first in Philadelphia in a shabby basement apartment where I wrote a poem called, I believe, “Father”—which Olson roundly criticized in the margins via letter, but he also cited a few lines that had some merit and suggested a way into the poem. Then, a year later, in 1956, after I hitchhiked across country to join some ex-Black Mountaineers in San Francisco, the desert stretches of the southwest along Route 66 impressed me so deeply that once I was settled in a cheap one-room apartment on the shady side of Nob Hill, I began a long poem called “The Desert”—which, after some more criticizing and suggestions about the poem from Olson, again via mail, I soon began to see, given my tendencies, had to be a story and one that turned out to be rather a long one. (It was published soon after by editor Don Allen in Grove Press’s “San Francisco Scene” issue of the Evergreen Review.) But, again, the poem often led me to my better half, narrative, and often thereafter, inspiration that started out as long poems really served as the kick back to the track where I had surer footing—story.

LS: Pagan Days seems a rather different kind of fiction from either Baths or Satyrnalia. How did you arrive at its composition? How does it relate to those previous books? I might as well go ahead and ask you about To Kill a Cardinal, too, a very different book from all three of its predecessors.

MR: I think Pagan Days relates to Baths and Satyrnalia as a continuum of the “I in the eye,” the eye that sees openly and without equivocation, and that presents the truth it sees. I wrote Pagan Days because I was intensely curious about the mysterious world of childhood, about the humanity and inhumanity of children. Pagan Days reveals, I suspect, how the early deep imprints of childhood from those who surround us shape us while at the same time triggering primal wirings of all our contradictions evolved over eons, the wildness and tamings in what makes us human in mind and spirit—what makes the pint-sized, solipsistic savage in us fit for family, fit for society. In the never-appeased hunger for power and for love amidst hatreds rooted in fear, in jealousy, in the sadism and masochism of deliberate cruelty and abject degradation, the early manifested root of the erotic (male infants born out of the womb already sporting tiny erections), all of it is a maelstrom in that welter of the uncertainties in the still-forming frontal lobes. And that certainly includes the goofy, swelling joy of the brandnewness of everything through a child’s eyes and senses in the awe and delight of just plain being alive in those endless green summers of childhood.

Saint Augustine said, if you’ll pardon my altar boy Latin, “Inter urinas et faeces ascimus”—“We are born between piss and shit”—and so at bottom are our primal pleasures, our regenerations and our degenerations. Without words for it, kids know this from the start like a second skin in their sentient being. I became possessed about all that, how it all seems to manifest itself in us so early, the child already evidence of the man or the woman to come in all the complexities.

So where to start such a book? Well, obviously in the life of the child still kicking within me, to begin at the beginning in the very womb itself, and, for better or worse, that’s how Pagan Days began. And the rest of it was written in the voice of a child, when I finally tapped into it, Mickey Lithwack.

And again, yes, I agree: the novel To Kill a Cardinal is “a very different book from all three of its predecessors.” Perhaps satire is the only recourse the powerless have as linguistic saboteurs to mock the pomposities and barbarities of the privileged and powerful (“those who cost others at no cost to themselves,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald so searingly revealed in The Great Gatsby), to prick tough hides with stinging barbs of the poisoned arrows of truth tipped in lethal irony. As poet and playwright Carl Morse stated in his comment on the book: “Whitman said that ‘the attitude of great poets is to cheer up slaves and horrify despots.’" To Kill a Cardinal extends this happy axiom to prose.

LS: Charles Olson’s name has come up again and again in your answers, and he’s a large presence in your memoir Black Mountain Days. At the same time, it’s the “I” in that book who seems to me the central figure, another development of the “I in the eye.” What was your intention in writing the book? What do you think you accomplished? How satisfied are you with your portrait of Olson?

MD: In the mid-1970s, at the urging of the late George Butterick, Olson scholar and curator of Olson’s papers in the archives at the University of Connecticut, I began to collect my heap of notes and write out of them my memories of Black Mountain. This led to my writing “Robert Creeley at Black Mountain” and “Meeting Charles Olson at Black Mountain,” two pieces that I later threaded into Black Mountain Days. But aside from those two forceful influences, among any number of others in my three years at the college, my plan was to include everyone from the cooks, Malrey and Cornelia, to farmer Doyle Jones and wife Clare, to all-around hand TJ, as well as the students and faculty members—in short, those of us who peopled that strange and exhilarating 600 acres in the mountains of western North Carolina in the early 1950s. I wanted to make that sense of place as complete and alive as possible, to include the rampant sexuality and my own first fumbling, wet-behind-the-ears romance with another student side by side with the amazing, innovative teaching and work done there, the “I in the eye” my journey from a raw and largely innocent, unawakened youth to someone who finally achieved what he had been driven to Black Mountain to discover: to shed the dead skins of all I had previously learned and to grow awareness of new reaches within me, new possibilities, the stretch of horizons. Central to that was to learn how to write, and that I found through the sometimes painful proddings but often dynamic teaching and guidance of Charles Olson. So I began to put down in words as much as I could of just what it was like to be a student at Black Mountain College in those years. Until Fielding Dawson’s Black Mountain Book appeared in 1970, several people had wondered why no students over its twenty-five-year history had ever written a book about what it was like to be at that unique and magical school. For better or worse, Butterick thought I was up to the job and pushed me to it. He’d expressed reservations about Fielding’s memoir, but Dawson, who had heard me read parts of my “Robert Creeley at Black Mountain” at a mutual reading we gave at the Poetry Project in New York, generously and insistently urged me to also write the book. It took, in fits and starts, about twenty-five years—as long as the school itself actually existed—to finish the task, with several other books in between, which you’ve cited. It was well worth the trip.

Sadly, George, to whom I dedicated Black Mountain Days as “the inspirer,” didn’t get a chance to see it in print in 2003, since he died of cancer several years earlier. But over those years of composing it, I sent him each segment that I was writing, and his suggestions, not to mention his enthusiasm, were invaluable.

Of course the “I in the eye” was my main focus—again, keeping it to This is what I saw, This is what I heard. I wasn’t interested in, or capable of, writing an academic or scholarly approach to Black Mountain—and besides, by that time Martin Duberman had published his fine and thorough history Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community in 1972. (Two other equally fine and thorough studies came later, Mary Emma Harris’s The Arts at Black Mountain College in 1987, and Vincent Katz’s Black Mountain College: Experiment in Art in 2002.) What I could do, through keeping my eye on memory, was to put as vivid a human face on that experience as best I could, and fortunately during that long time of composition the memories were still clearly visible and fresh in my mind. Duberman, in his comment on the book, aptly caught the spirit of my intent as putting “personal flesh on Black Mountain College’s historical bones.”

What took me the longest to write about was my attempt to get down (get to the bottom of) my often thorny and tangled experience with Charles Olson, my mentor and eventual awakener. He so invaded and enchanted my still-green years, as he did so many of us who fell under his charismatic spell, I wanted to make some sense, if only for my own sake, of the ambiguities and ambivalences, the frustrations of my desperately wanting to please him, to have him find in my rudimentary scribblings something at last worthy of his praise and his acceptance. I had given up on ever getting any of that from my own father. I was stubbornly determined that with Olson, as “spiritual father,” whether he liked it or not, I would not give up. And I didn’t.

So that journey with Olson, down many a twisted tributary, often confusing and even more times filling me with hopelessness, finally led to a way out and a way to my own path into writing.

What was difficult about writing about Olson, aside from my own demons swarming within me at the time, was my trying to understand him, which I finally saw was impossible. As soon as I thought I had a hold on him, Olson, mercurially, like all great genius, slipped away, assumed other shapes. As much try to understand the unknowable creator of the universe as to figure out a great and protean maker plugged into that vast and mysterious wonder. The roots, finally, were best left shrouded in mystery. So, I let it go. There was no end to him, as his continuously living works show, his Maximus, just as there is no end to the cosmos as far as we know, and what mortal among us will ever know that?

LS: Last question. Recently we lost Jonathan Williams, an extraordinary poet and publisher among many other things, who also learned from Charles Olson at Black Mountain College. Can you comment?

MR: Yes, there sure is a lot to say about Jonathan Williams, much that I could say here but have said in Black Mountain Days. That he was a dynamic force for poetry and for his publishing his Jargon books has been noted in the extraordinary outpouring singing his praises in the obituaries, nationally and internationally, following his recent death. Jonathan, first and foremost, cast a sharp and affectionate eye on what is overlooked in both people and places in this land of the overlooked. He will be sorely missed, but his considerable accomplishments in his wonderful, witty and lively poems, and in his fine and beautiful books, remain and will continue to delight us.

My admiration for Jonathan, for his work and his well-lived life, is pretty much summed up in a March 14 letter I wrote to him, which sadly, since he died on March 16, he never got to read. I read it at a tribute to Jonathan as part of the Black Mountain College Celebration in September 2008 at Lenoir-Rhyne College in Hickory, North Carolina. I include it in conclusion here as my own personal tribute:

Dearest Jonathan,

Belated March 8th birthday greetings. Am most distressed to hear that you’re laid up in the hospital—what a rotten place to welcome in your 79th year. Hope your illness turns round in this turning of the season and you will be back with Tom in dear old Highlands in that beloved home the 2 of you have made there together over many a year now since first meeting at Bard. Just the thought of those gorgeous surrounding mountains going that heartbreakingly smoky green in the commonplace miracle of spring is something I sure hope you’re at home again to see, you who have brought that same sense of miracle into the enchanting and delightful freewheeling handsprings of your many years of writing and singing out loud your “pomes,” as Whitman called his (and, were he around to hear them, would I betcha’ give the nod to yours hands down).

Well, I had my 76th on March 5th, which makes us fellow Pisceans (“the old souls,” as Olson might’ve said), the poets and the dreamers, the visionaries—Not sure I can claim much of that for myself, but evidence of that is certainly in your work, both in its written form and in all the work you’ve done for so many decades, keeping the word alive and sprightly in all its authentic nooks and crannies, in all the equally authentic overlooked spirits hidden in plain sight throughout the piedmont and hills of North Carolina, throughout the Southland and wherever your feet and that old station wagon took you roaming and looking. And the books—yes, those superb and beautiful books you made: what a grand treasure for all our eyes. What a grand treasure and illumination your life has been in these benighted States, in these benighted times.

Well, old fellow Black Mountaineer—old Black Mountain-ear—wasn’t that a gift and pleasure, despite the hardships, to have been there, to have found our feet on that lively (sacred?) ground. Sure were lucky. And among so many that I met and cherished there, whose memory I’ve kept in my heart all these years, including your own, since we all scattered out into the world after Black Mountain closed, well, those memories have and still are riches beyond riches.