by David Beard

Comics publishers republish older material not only for its artistic relevance, but also because republication is very profitable; prior to the ’80s, industry giants like Marvel and DC employed creators on a “work for hire” basis, with the company owning the rights to the stories and characters outright. Eventually creators began demanding a piece of the action in the contracts they negotiated, but generally speaking, when comics created prior to that are collected and reprinted, revenues generated for the publisher are nearly pure profit.

Partly for that reason, Marvel has reprinted its comics of the 1960s and 1970s a near-uncountable number of times, including the story of Adam Warlock. Initially published in various series between 1967 and 1977, this character’s tale became widely heralded as a masterful execution of superhero comics. Originally a third-tier character created by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee in the pages of Fantastic Four and Thor, Warlock was a petulant infant in a super-powered body—a mere seed of an idea used mostly as a plot device during a time when comics were measured by the number of punches thrown.

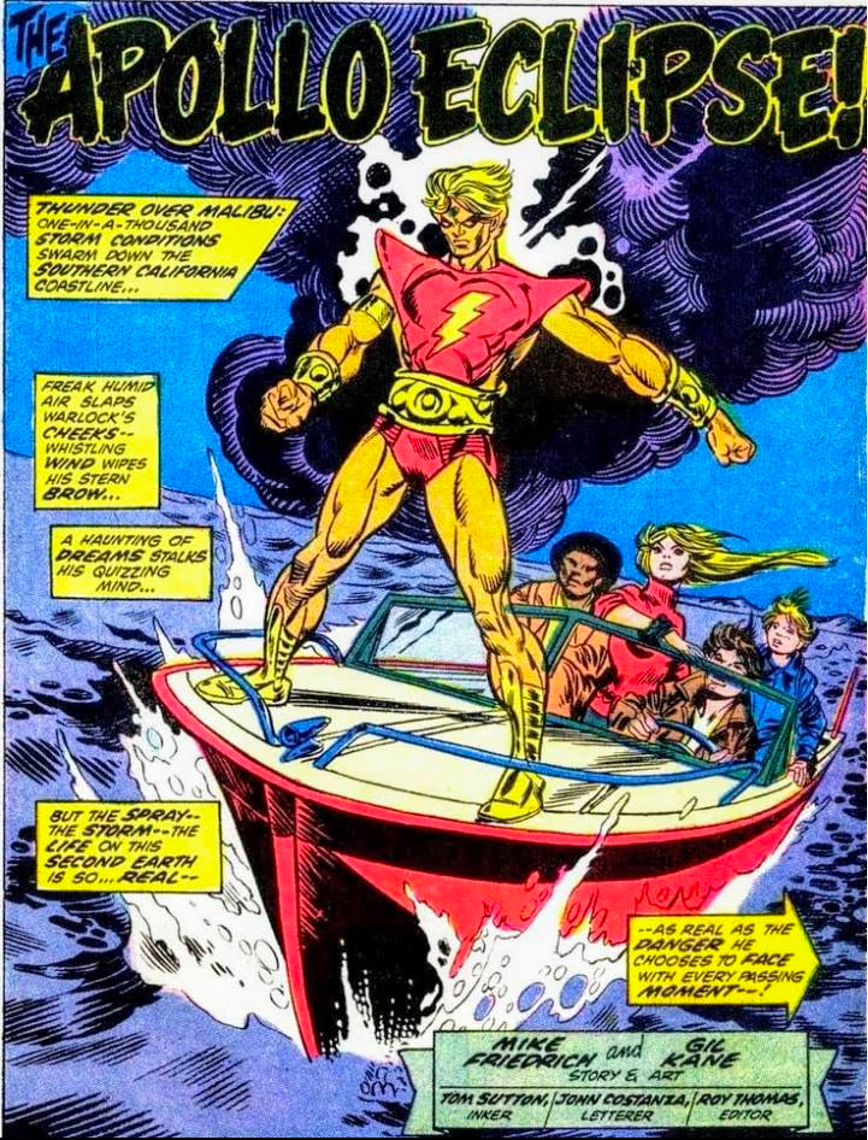

The seed was watered when Roy Thomas and Gil Kane (abetted occasionally by other creative hands) revived the character in 1972; they developed both the first man theme (note the character’s first name) and added a Christ allegory. In their version, Warlock was a pacifist called to fight to save humanity; his enemy was a “Man-Beast” leading humans down the path of violence, suffering, and death. Stirring moments intentionally and unabashedly echoed Gospel scenes, as can be seen in this illustration’s allusion to Jesus and the apostles in a storm:

Thomas and his collaborators used such allusions to the New Testament (and to Jesus Christ Superstar, a popular Broadway musical at the time) numerous times in their run from 1972-1973 before the series was canceled, but Warlock wouldn’t have long to wait for a revival: In 1974, a rising star creator at Marvel, Jim Starlin, reinvented the character. Starlin attempted to be as close to an author as mass-market comics would allow at the time, writing, drawing, and even coloring the first installment of Warlock’s story himself. (The only help he received in assembling the issue was from Annette Kawecki, who drew the letters on the page.)

For the next three years (one month at a time, in about twenty-page chapters), Starlin told a story of memorable complexity and originality. His Warlock fought “the Universal Church of Truth,” which extended its reign across the galaxy by offering new species a choice: either join the Church or be eradicated. But Starlin used the narrative to critique more than institutional corruption and the broken psychodynamics of religion. The Church was led by a villain called the Magus, and when Starlin revealed that the Magus was actually a future version of Warlock, the story explored a common anxiety among the young: the fear that as they age, they will become as corrupt as the elders they decry.

In our current time, readers of Starlin’s Warlock saga and his similarly reimagined Captain Marvel series of the ’70s can see resonances within the Marvel Cinematic Universe. In the Avengers movies, the villain Thanos seeks to collect the infinity stones so that he can end half of all life in the universe as a solution to overpopulation. Only the Avengers can stop him, in a powerful battle that demands sacrifice among them (and takes hours of digital animation).

But Starlin’s comics made the point even finer; in their telling, Thanos seeks to collect the infinity stones to end all life, and he does so as a love offering to Death, depicted as an embodied character. To younger readers today, this may be hard to connect with; it’s difficult to explain the poetic, indeed Romantic tradition of embodying death that suffused 1970s popular culture. Death was always dark and powerful, like a grim reaper, and often sexy and alluring, like a lover; she appeared as such on countless heavy metal album covers and comics—especially Jim Starlin comics. For example, in Starlin’s 1982 graphic novel The Death of Captain Marvel (the very first original graphic novel published by Marvel Comics), the character interacts with the embodiment of death as he grapples with his own terminal cancer:

In the Avengers movies, the heroes are defeated by Thanos in Infinity War, then rally to victory in Endgame. In Starlin’s comics, Thanos defeats the Avengers and there is no salvation by heroes—only Adam Warlock, fulfilling his messianic overtones, can defeat Thanos, and only at the cost of his own life. Starlin’s original version offers a more satisfying literary conclusion, though of course, as always in the comics medium, the door was left open for future iterations of the character.

The story of Warlock, then, begins in the 1960s as a plot device, moves through a clever but incompletely envisioned character arc built around the Christ story, and finally becomes a vehicle for political statement and emotional drama. While the parts of this sequence have been reprinted many times in various formats, they can now be found together in the Adam Warlock Omnibus (Marvel, $125) released earlier this year, which collects everything from his early appearances in Fantastic Four and Thor to the end of the ’70s Starlin epic.

As a whole, the Warlock story has been immensely valuable to Marvel for more than forty years, and perhaps gave a leg up to Starlin too; subsequent to this series, he was one of the first artists who were able to sign contracts with Marvel and other comics publishers which gave him ownership of his work. His most significant opus over this time has been Dreadstar, in which the eponymous rogue and a ragtag band of comrades are squeezed by the imperial Monarchy on one side and the theocratical Instrumentality on the other, picking up on the critique of organized religion and politics Starlin first introduced in Warlock. Transposed from a superhero narrative into a science fiction one, Starlin’s Dreadstar loses the optimism inherent in Warlock, but it certainly retains the emotional drama, thematic complexity, deft characterization, and eye-popping draftsmanship for which his body of work is justly acclaimed.

Disappointingly, however, Starlin’s success in negotiating ownership of works like Dreadstar has resulted in making these books more of a niche attraction; while Marvel cranks out new editions of Warlock over and over, paying Starlin nothing for the honor, Starlin has had to crowdfund the most recent edition of his creator-owned comics. Still, Warlock remains an impressive example of Jim Starlin’s early work and tenure in the comics medium.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023