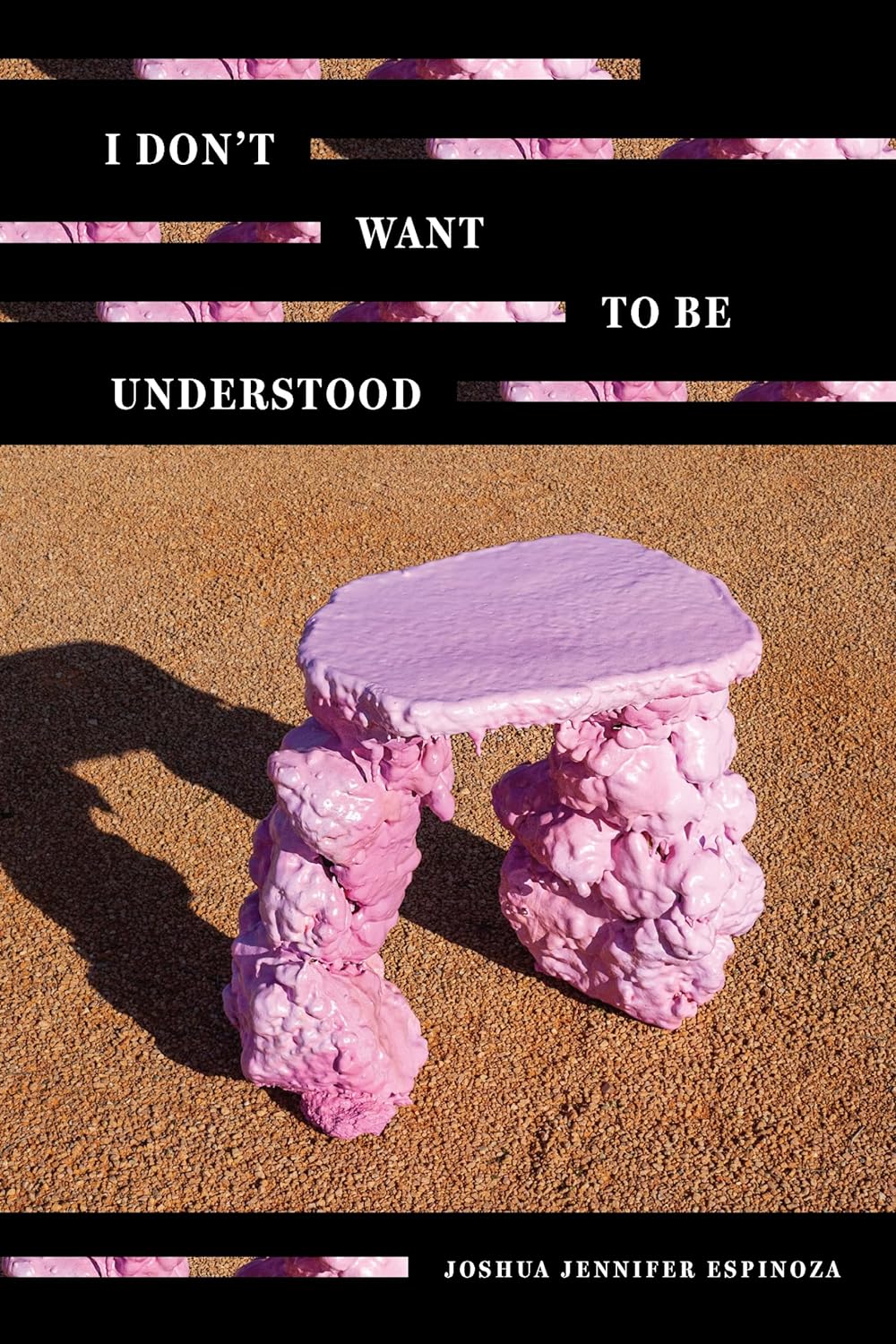

Joshua Jennifer Espinoza

Alice James Books ($24.95)

by Oscar Ivins

In Joshua Jennifer Espinoza’s collection I Don’t Want to Be Understood, anti-trans sentiment is both structural and structuring; the atmospheric quality of transphobia affects what and how the poems’ speaker dreams, dreads, desires. A hauntingly intimate portrait spanning a life from childhood to today, the collection is deeply attuned to both the harsh and harmonious pitches that accompany experiences of transition in a society that is hostile to trans happiness.

The collection is inwardly panoramic. As the speaker, “a light in the form of a girl,” travels through courthouses, airports, and a menswear outlet in Hollywood, we are beamed into the neglected—and sometimes purposefully avoided—corners of her mind.

The opening poem, “Airport Ritual,” offers a science fiction twist on the anxiety-riddled experience of going through airport security while transgender. An epigraph stating “The following is a true story” conjures the paradox of security scans: Your body is intimately scrutinized while you’re told it’s not personal. “An anomaly is spotted. A woman is taken aside.” Then a TSA agent informs the traveler that she will need to touch her. When the traveler shares that she is transgender—“unsure if she means this an a warning or an apology”—the poem shifts register into absurdism: “the thing in her pants that set the sensors off suddenly expands” and keeps expanding to fill the terminal, the airport, the city of Irvine, until the military is called in.

By invoking facticity before bursting into the mythic, Espinoza teases and subverts cisgender expectations of what a trans narrative should do. The poem’s epigraph signals a common complaint made by trans people about trans literature: As transgender writers gain relative prominence, often the books that sell the best are the ones that cater to a cisgender audience. Whether that means work that flattens transition into an “it gets better” narrative or work that is overly expository to the point of redundancy, it is a reality of the publishing industry: Sometimes the only way to achieve a modicum of financial success is to fit one’s work into a preexisting box, one constructed by the institutions of cisness.

Reading “Airport Ritual” as a trans person, I feel deeply the truthfulness of this story—the dread and anxiety that arise from this kind of interface with the state. In the poem, while pundits discuss the benefits of forcing trans people into detention facilities,

The woman at the center of the plasma or whatever-the-fuck-it-is

just wants someone to say one thing to her

that doesn’t feel like kite string wrapped around an open wound

in a warm, strong wind. But it doesn’t happen.

Through this play between literalness and absurdism, Espinoza flips the cultural script that says trans people are delusional and transition is science fiction, instead casting the cisgender state as the true site of hysteria. While cis society turns up the dial on fascism, the woman at the center of the poem is simply trying to live.

One of the most compelling aspects of the collection is the way it portrays transition as transcendently positive at the same time as it is traumatizing. A common trope of trans cultural production is the idea of transition as linear. In this formation, one’s life before transition is rife with confusion and anguish but through transitioning the pain of daily existence is relieved; one becomes stronger, life becomes better. This is not untrue, and Espinoza’s work highlights how transitioning is a way of getting off autopilot and pursuing embodiment on one’s own terms. In “The Present,” Espinoza describes the dissociation of closeted life:

For a lifetime, sensation was

a single thread

in my wardrobe of pain.

It is a metaphor more easily grasped in the reverse: pain as a single thread in the wardrobe of sensation. Through this inversion Espinoza deftly shows how dysphoria can warp and narrow experience and lead to self-alienation. As the poems in this collection express, to transition is to leap into feeling more.

Yet as Espinoza’s speaker becomes more connected to herself and to her life, she also registers the pain that has surrounded her—she can no longer dissociate through it. Espinoza’s attention to the family as a site of violence is particularly affecting. In “To My Parents,” she writes, “I was the mantle above the fireplace, the one that held our portrait. // I was the frame around the photograph, but not the photograph.” Being a closeted trans person can feel like being the one holding it all together while living as a background fixture in your own life. The speaker’s religiously inflected childhood trauma, her youth spent hiding and self-numbing, shape the psychic landscape years after she has left home, come out, and her mother’s gotten a “trans ally tattoo.” In this way, transition can make life feel harder when you are experiencing the pain your mind has protected you from—as Espinoza writes in the resplendent “Return to Light,” trauma “reminds you to forget its presence.” I Don’t Want to Be Understood posits that through this remembering and daily survival, we can do more than find ourselves: If we are lucky, we can create ourselves.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2024-2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025