Aby Kaupang and Matthew Cooperman

Aby Kaupang and Matthew Cooperman

Essay Press

by Carol Ciavonne

On the way to the psych ward there are elevators that are glass and elevators that are steel this is clear most designers and children who do not die in helicopters prefer glass elevators

If Disorder 299.00 were not a digital chapbook, it would have to be bound in steel and glass. The photocopied cover, in fact, appears to be steel, printed with an image of faceless (removed ovals of steel) mother and father, and their lovely (intact) baby. Mother and father are dressed in conventionally gendered attire, as if to show the traditional expectations of parenthood. But this will not be a traditional experience for poets Aby Kaupang and Matthew Cooperman, or for the reader, and the title of the book is the first indication.

The girl began, and then so did the book, a mirror for sorrow

or anger or fear.

For Kaupang and Cooperman, this is family life; uncountable trips to medical entities to try to find help for Maya, who is autistic and also has life-endangering physical problems.

Again and again at the ER

soothing her body. The daughter didn’t eat, didn’t

sleep, didn’t laugh, didn’t shit, didn’t walk anymore. We

went for a long visit. Doctors said erythromycin, they said

tape a bag to her shoulder. We went again when they said

she was crazy, a crazy summer when our little girl lived with

other un-specifiable children.

Maya is labeled in the hospital system as 299.00 “unspecified diagnosis.” Although this label is troublingly nonsensical, labels are a literal fact of life for the family. Aby is MOC (Mother of Child) in the endless documents of hospital visits, Matthew is FOC.

I went to the pharmacy she was not there

I went to the surgeon she was not

there

I went to the TV the nurses’ station the family respite station

she was not there I was not therea we everywhere

MOCs and FOCs as assemblies

of pills

The authors have so much of labeling that they invent a word for themselves, the other MOCs and FOCs, and the children being cared for.

cardiums: heart bouquets, whack jobs

staring

they that were the cardiums wore it on their sleeves their crimson gowns

forehead temples and they wagoned there were they that were in the wagons

and those that carted others in wagons it was numerous who or who all were cardi-

umsthey passed through the foyer we drank coffee averting our eyes from sadness to

sea tanks we admired the sea tanks we too being cardiums

Kaupang and Cooperman write in a variety of syntax, in the distancing acronyms as well as the personal I or we, their experience as helpless, sometimes desperate parents, and as individuals who do sometimes vehemently desire their “normal” lives back.

The difficulties of caring for Maya physically, and the emotional roil of her health and behavior are laid out with no punches pulled. In this work, it’s clear that Maya’s condition compels the poets to constantly question themselves, as parents, as a couple, and as individuals. Their lives are often tuned simply to survival mode—Maya’s actual survival, and their own emotional survival. It’s a topic requiring deeply personal exposure of pain, anger, guilt, fear, and love.

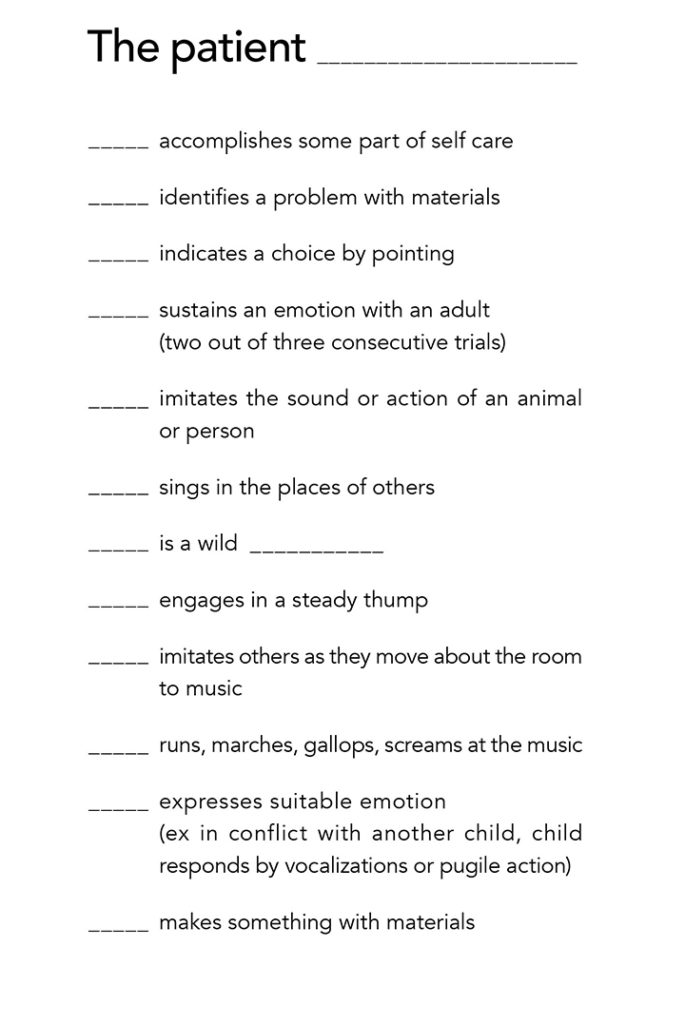

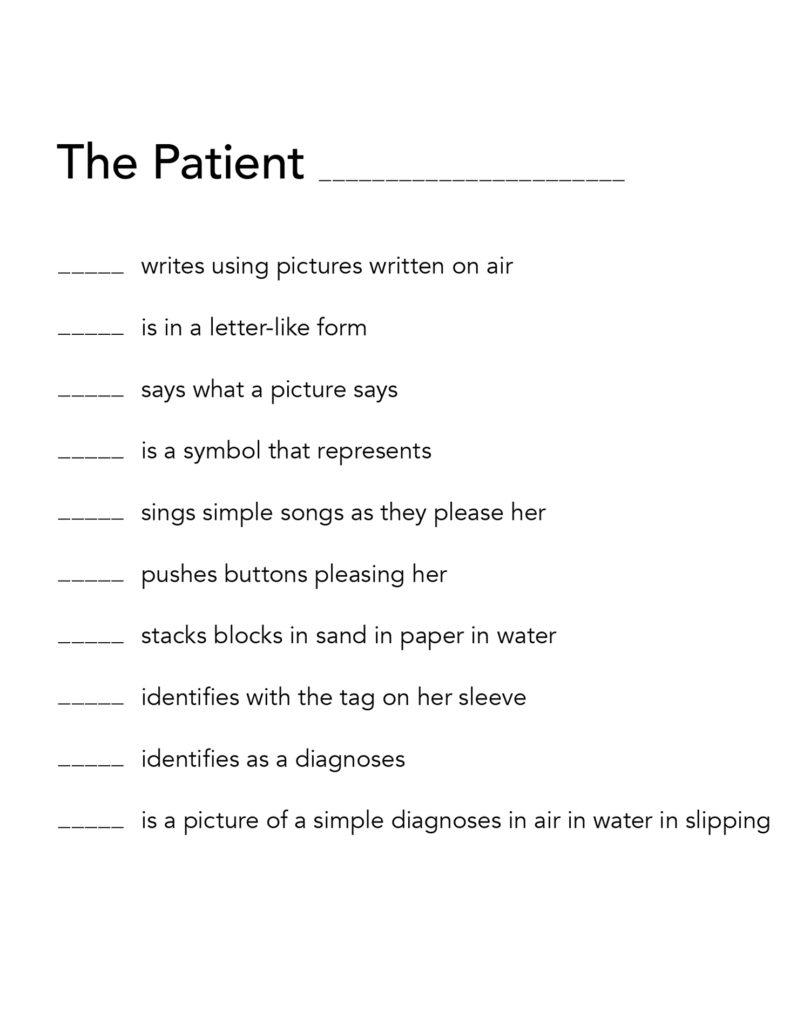

The structure of the book, using actual documents and forms, personal statements, statistics and fragments of description, is a near perfect dovetailing of content to form. The documents are visual evidence of the mind-numbing and heart-breaking forms that the authors must use to describe/report their lives and Maya’s within the hospital system. In some, both the child and the parents are described in the dry clinical style that seems to question the actions and observations of the parents. “The cause is unknown and that is vexing to the mother.” The forms, too, do not fit the patient, and the listed behaviors are impossible to check off. The patient is a form from the hospital; The Patient is a form created by the authors that demonstrates how elusive any description of behavior can be, and is especially so in Maya’s case.

As with the re-labeling, in redefining the limiting clinical language, the authors rewrite the hospital experience into one more human, less rigid, and somehow hopeful—more Maya, her actuality and possibility. Some of the textual pieces are clearly written by one poet or the other, illustrating how each individual parent sees and reacts to events, and yet the reproduced documents and the use of “we” also make it clear that this is shared experience. The fragmented syntax, a staple in post-modern work, makes particular sense in interpreting and reading the lives of Maya and her parents, with all the jolts, reverses, and accelerations of living with autism. This is a book that could be given to other parents of children in Maya’s situation, since one of poetry’s great virtues is to help us know that we aren’t alone. Even the incidents in the book that are particular to Cooperman’s and Kaupang’s experience resonate; the particular in poetry so often pierces a quite different heart. Some of the lines will be familiar to anyone who has had to be in a hospital with a loved one, and the lines are stark:

the truth of the hospital system is

death prevention and sometimes

death theft and the truth of the

ER more so . . .

Some of the lines are a personal revelation of love and the sadness of knowing that Maya’s life will not be as they had imagined it:

Present is

this gift of the daughter’s enormous need

and absent is the dream of her own dream

a blue house and yellow car, two Chinese dogs

and a child of her own.

Some are the experience every parent knows of that edge of love and fear:

I staunch the fear of my own death and her

perpetual childhood. Today was a good day.

The open and sometimes head-on approach in Disorder 299.00 includes the poets’ relating that some readers of the manuscript have questioned whether they love their daughter. No one who has not lived with the extreme rigors of caring for an autistic (and in these years, very ill) child, with the ever present fear of calamity, can completely understand the impact of a shared life that can lurch from control to chaos on an hourly basis, but Cooperman and Kaupang have made beautiful, blended, astonishingly honest and profoundly moving poetry of their experience. Although Disorder 299.00 makes a fine digital chapbook, I would love to see it in print also; it’s a book that needs to be on the small table in the hospital waiting room, where words of steel for strength, glass for looking through and into, are always needed.

Early in the book, the authors ask, by way of quieting the reader’s apprehensions of the future,

What is there to say of this child? She lived, lives through

this. So did we. You want to know more about her. So did

and do we.

The final poem is a portrait of Maya today.

WORDS FOR THOSE WHO DON’T SPEAK THEM

when our daughter rises it is with and without her mouth

she sings in phones of plosive thirds that do not complete

the scheme and yet they are awake they are very awake

third third third

she sings with her body and to her body a plateau of sinew

to hold a twitch of song

she moves the bed by pressing everywhere

up up up

she levitates the bed by hanging hours on the bed

our messenger she is out frontSong––

she sings in hunger or wetness

and we rise