a review of:

NEW SELECTED POEMS AND TRANSLATIONS

Ezra Pound

Edited by Richard Sieburth

New Directions ($16.95)

EZRA POUND TO HIS PARENTS – Letters 1895-1929

Edited by Mary de Rachewiltz, A. David Moody, and Joanna Moody

Oxford University Press ($65)

EZRA POUND IN CONTEXT

Edited by Ira B. Nadel

Cambridge University Press ($118)

by Patrick James Dunagan

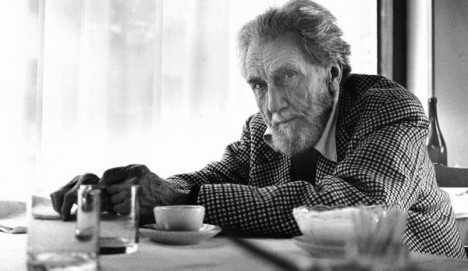

It is as though Pound never had illusion, was born without an ear of his own, was, instead, an extraordinary ear of an era, and did the listening for a whole time, the sharpest sort of listening, from Dante down. (I think of Bill Williams’ remark: “It’s the best damned ear ever born to listen to this language!”)

—Charles Olson, “Grandpa, Goodbye”

There’s been a great deal of brouhaha about Pound’s flagrant dalliances with anti-Semitic and/or fascist thinking. Though such concern is certainly pertinent to the act of reading Pound and unfortunately remains relevant in the world at large, given the horrendously destructive impact such hate-thought continues to have, there should be no question that Pound’s writings are necessary readings for anyone who undertakes a serious study of poetry. Simply put, Pound is the poet who moves twentieth-century poetry in English along. Without him, there’s a very large blank in which no other single individual’s work will suitably fit as replacement. Pound’s first decade of labor in poetry alone yields a range that none of his contemporaries move through during the same span of time. His consistent urge to realize an ever-evolving practice with both subject and form in the writing of poetry anchors the indispensable role his work plays.

More specifically, Pound pushed harder than any of his contemporaries to expand and extend the possibilities of poetry. From “Nahless I have been a tree amid the wood / And many a new thing understood / That was rank folly to my head before” (from “The Tree” originally included in the self-published HILDA’S BOOK written 1905-07 and dedicated to the poet H.D. during a period when Pound was her young suitor, barely in his twenties) on to “These were the swift to harry; / These the keen-scented; These were the souls of blood” (“The Return”) after which comes, “Whirl! Centripetal! Mate! King down in the vortex, / Clash, leaping of bands, straight strips of hard colour, / Blocked lights working in. Escapes. Renewal of contest” (“The Game of Chess”). His early work is a series of one push rejected by the next push. Always breaking new ground, he is never to be found settling down into any easy satisfaction.

This relentless urge reaches a crescendo with his poem “Homage to Sextus Propertius” when Pound crashes the genteel academic bent of translation by including sensible problems of the Modern era in the work (the classical era Roman poet Propertius dates well before any worries over a patent existed, let alone one for the Frigidaire).

My orchards do not lie level and wide

as the forests of Phaeacia,

the luxurious and Ionian,

Nor are my caverns stuffed stiff with a Marcian vintage,

My cellar does not date from Numa Pompilius,

Nor bristle with wine jars,

Nor is it equipped with a frigidaire patent;

And it is because Pound is so assured of his skill—having engaged innumerable hours of his time to reach the more than adequate abilities that he displays, he is able to join his own words with those of Propertius, declaring:

Yet the companions of the Muses

will keep their collective noses in my books,

And weary with historical data, they will turn to my dance tune.

So strong is Pound’s deliberate aim to present an inseparable mixing of himself with the literary and historical Propertius, that “my” may as be easily read as “our.”

As editor of the New Selected Poems and Translations, Richard Sieburth excellently puts Pound’s genius in perspective:

Pound’s tonal strategy in this “homage” is deliberately anachronistic, for while attempting to capture “the spirit of the young man of the Augustan Age, hating rhetoric and undeceived by imperial hog-wash,” he also sought (as he wrote in 1931) to present “certain emotions as vital to me in 1917, faced with the infinite and ineffable imbecility of the British Empire, as they were to Propertius some centuries earlier, when faced with the infinite and ineffable imbecility of the Roman Empire.”

Pound’s tonal strategy in this “homage” is deliberately anachronistic, for while attempting to capture “the spirit of the young man of the Augustan Age, hating rhetoric and undeceived by imperial hog-wash,” he also sought (as he wrote in 1931) to present “certain emotions as vital to me in 1917, faced with the infinite and ineffable imbecility of the British Empire, as they were to Propertius some centuries earlier, when faced with the infinite and ineffable imbecility of the Roman Empire.”

While it reads like a novel, Mary de Rachewiltz, A. David Moody, and Joanna Moody’s new edition of Pound’s letters,Ezra Pound to his Parents, unavoidably leaves out or glosses over all sorts of details. Pound is, after all, addressing his middle-class parents in the rather conventional Victorian fashion in which he was raised. Nonetheless, this very handsome book is quite valuable. Of course this is a one-sided view of the poet’s life, but Pound the individual is brought one remove closer, as further evidence of his character, chief interests, and pursuits is given in often weekly detail over the stretch of years during which the manifestation of his core poetic beliefs takes place. He is a schoolboy when the letters begin and a well-known, published poet with wife and child (along with mistress and another child) when they are brought to an end.

He is most dutiful in reporting his various locations, both physical and textual, as he manages ratchet up his presence on the literary scene, living first in London, then Paris, then London again, until finally settling in Rapallo with many travels about Europe in between. The common topic is any such “nooz” (as is Pound’s want for spelling “news”) or else lack thereof: “No news here except that I am going to be transferred to some more advanced work in German” (writing from Hamilton College during January 15-18, 1905); “I don’t know there’s much news” (writing from London on Aug 5 1912); “Don’t know there’s much new” (writing from London on Oct 24, 1914); “Don’t know there is much new to report” (writing from Paris on Aug 24, 1923, where he finds himself hanging around with Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemmingway, and William Carlos Williams).

While the letters do not reveal anything fresh, they do offer an intimate look at how Pound passes his time. And the fact that all of the letters to his parents are here, from his earliest years on, is a sheer delight. He is by turns sardonic (“It is rather late in the day to go in to the whole question of realism in art. I am profoundly pained to hear that you prefer Marie Corelli to Stendhal but I can not help it”) (To his Mother [Jan 1914]) and dismissive (“I wish those of my American friends who really want specimens of my immortal scrawls would begin to order the same thru Wanamaker or Brentano, because no firm is going to import English publications until there is some faint indication of a demand, of course Matthews wont begin to print the ‘Dawn’ until ‘Personae’ has paid for itself”) (To his father [after May 1909, London]).

It’s a given that the unending burden of entering into a full-scale reading of Pound is substantially weighed down by the fact that there is so much to read. Yet a collection of essays such as Ira B. Nadel’s Pound in Context is an essential go-to reference. Here, all the pesky W’s that ever disturb the back of the brain while reading—Who, What, Where, When, though hopefully not Why—get at least some attention. The encyclopedic entries have clear headings by way of themes (“Visual Arts,” “Law,” “Dante and early Italian poetry”) along with locales (“Paris,” “Venice,” “London”) all written by a array of scholars, such as Ronald Bush, Tim Redman, and Leon Surette. The book is divided into three sections: “Biography and Works,” “Historical and Cultural Context,” and “Critical Reception,” making it easy to locate whatever information a reader seeks. This critical collection is the handiest one volume guide to everything on Pound imaginable.

For the many texts Pound is known to draw upon, there are yet passages in his work which remain surprisingly refreshing. At times, even The Cantos are clear enough of literary reference that his crystalline vision arrives strikingly direct and is easily approachable:

and Brother Wasp is building a very neat house

of four rooms, one shaped like a squat indian bottle

La vespa, la vespa, mud, swallow system

so that dreaming of Bracelonde and of Perugia

and the great fountain in the Piazza

or of old Bulagaio’s cat that with a well timed leap

could turn the lever-shaped door handle

It comes over me that Mr. Walls must be a ten-strike

with the signorinas

and in the warmness after chill sunrise

an infant, green as new grass,

has stuck its head or tip

out of Madame La Vespa’s bottlemint springs up again

in spite of Jones’ rodents

as had the clover by the gorilla cage

with a four-leafWhen the mind swings by a grass-blade

an ant’s forefoot shall save you

the clover leaf smells and tastes as its flower (“Canto LXXXIII”)

Of course, in this particular passage from The Pisan Cantos, in addition to containing language other than English, Pound refers to being imprisoned outdoors on a U.S. military base in “the gorilla cage” after the end of World War II on a charge of treason. But left without books for reference and only his memories to draw on, he minutely studies the world surrounding him and presents a scene rich with gripping immediacy.

Pound’s new Selected Poems edited by Richard Sieburth does a fine job of sifting through the heftier Cantos for readers. Slicing out sections from among the longer passages, Sieburth allows for the finer points to be easily appreciated without subjecting readers to the mire Pound often tosses in with such good measure. While there’s something to be said for the slog of the economic and historical Cantos (particularly passages concerned with the early U.S.), which advances a reader’s ultimate appreciation for the work (much like Melville’s chapters on specifics of the whaling industry in Moby-Dick), no harm comes from this attempt to draw in readers. Those who are left with the urge to know more about Pound and his work will shortly discover the hurdles when they read the full Cantos—which will be, of course, an inevitable undertaking.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2013 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2013