Edited by Mary Jane Jacob and Kate Zeller

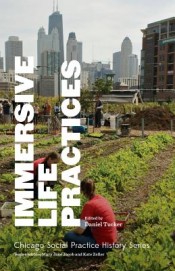

Immersive Life Practices

Edited by Daniel Tucker

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago / The University of Chicago Press ($20)

Support Networks

Edited by Abigail Satinsky

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago / The University of Chicago Press ($20)

by Jay Besemer

Going Deep: Chicago-Style Social Practice

1. Some Context

How are people free to work experimentally—and prevented from working—with culture tools? How have various artists and community members created resistant and alternative models for both artistic and life practices, often blurring and blending the distinction between the two? How do these people, groups, and practices relate to traditional infrastructures for art and culture-making, especially regarding access to support systems, space, funding, and sustained income opportunities? Finally, what might the answers to these questions tell us about our own sense of possibility for meaningful life, whether or not we call ourselves artists? These questions and more are posed by the branch of cultural production known as “social practice.” They are deeply important for residents of today’s Earth as we grapple, individually and collectively, with our varied and intensely problematic conditions of life.

In late 2014, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) launched an ambitious and intense series of social practice-related programming. Much of it centered around an exhibition entitled A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action. On view in SAIC’s Sullivan Galleries between September and December of 2014, this show and its surrounding series, A Lived Practice, led to the publication of four 225-page anthologies documenting some of the various social practice efforts and approaches throughout Chicago history. Two of the four volumes are especially compelling to readers interested in the aforementioned questions. These books, Immersive Life Practices (edited by Daniel Tucker) and Support Networks (edited by Abigail Satinsky), explore the relationship of Chicago-centered artists to the global social practice community.

In late 2014, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) launched an ambitious and intense series of social practice-related programming. Much of it centered around an exhibition entitled A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action. On view in SAIC’s Sullivan Galleries between September and December of 2014, this show and its surrounding series, A Lived Practice, led to the publication of four 225-page anthologies documenting some of the various social practice efforts and approaches throughout Chicago history. Two of the four volumes are especially compelling to readers interested in the aforementioned questions. These books, Immersive Life Practices (edited by Daniel Tucker) and Support Networks (edited by Abigail Satinsky), explore the relationship of Chicago-centered artists to the global social practice community.

The term “social practice” has many definitions, but in general it can be described as artistically informed experimentation, demanding deep and long-term research of places, systems, and relationships. An investigative element is often present, as is a collaborative and non-hierarchical mindset and methodology. One fairly well known example of a long-term social practice project—albeit not Chicago-based—is Mel Chin’s ongoing “Revival Field.” This project has some elements in common with efforts made by Chicago artist Dan Peterman, founder of the Experimental Station. In an interview toward the end of Immersive Life Practices, Peterman provides a useful functional description of his own artistic experimentation:

It’s a kind of a continual assessment of materials and processes that in various ways track meaning or value. In a sculptural or artistic sense, this is not just about transforming things with an aesthetic toolkit into art, but recognizing all these dynamic relationships. So it is very time-based. Meaning it is constantly changing because there are various economies at play.

Because social practice orientation tends toward engagement with problems rather than outcome-focused single solutions of problems, it is well suited to deep and thorough play with complex, often ongoing issues for which a finite “solution” tends to mean erasure or marginalization of minority concerns. On the other hand, projects in social practice can demand a slow-developing and indeterminate trajectory, making them ill-suited to many artistic funding models, market-based valuation, and pathways to arts-related institutional oversight or affiliation. In short, the discipline spotlights the failures of the traditional support systems of arts practice, and enables (even demands) an enlightened pragmatism of working alternatives to existing paradigms and methods of support. These characteristics of social practice, in general, provide the scaffolding of our discussion here.

2. A Chicago School: Roots and Shoots of Social Practice

The Lived Practice series was rooted in the ideas and actions of John Dewey and Jane Addams, both of whom were important figures of Chicago history. The community-service cultural ethos modeled (and pioneered) by Jane Addams’s Hull-House was especially vital. Combining social and educational services for immigrants with an art gallery, performance space, and other art-positive supports, Hull-House offered a rich experiential alternative to exclusionary social systems and art venues. The Dil Pickle Club, an early 20th-century class-scrambling venue located in Chicago’s Towertown neighborhood, is another relevant alternative-arts prototype.

Abigail Satinsky introduces Support Networks with the explicit connection between past and present, exhorting readers to

draw connections with the Dil Pickle Club or Jane Addams’s Hull-House as historical progenitors, as relevant to social practice artists as museums, galleries, and artist-run spaces, and start interrogating the actual conditions of building community within a range of political contexts and social histories.

In many ways the connection is quite clear; Theaster Gates’s Dorchester Projects shares a lot in common with the ethos and function of Hull-House, serving both as a residence and as an archive/cultural venue, located in an African-American neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side that is itself rich with history. Mess Hall, formerly located at the other pole of the city in the far-north Rogers Park neighborhood (and now defunct), echoed some of the Dil Pickle ethos. This collective-run space offered educational and artistic programs driven by a gift economy of mutual aid rather than monetary focus; no exchange of cash could take place in the space. The axes formed by these four examples across time and the city’s geography help to plot out some key social practice coordinates: analysis of economies; the role of class, race, and gender in access to resources; people-centered alternatives to dominant ideologies/methodologies; and the setting/function of making and experiencing art.

In many ways the connection is quite clear; Theaster Gates’s Dorchester Projects shares a lot in common with the ethos and function of Hull-House, serving both as a residence and as an archive/cultural venue, located in an African-American neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side that is itself rich with history. Mess Hall, formerly located at the other pole of the city in the far-north Rogers Park neighborhood (and now defunct), echoed some of the Dil Pickle ethos. This collective-run space offered educational and artistic programs driven by a gift economy of mutual aid rather than monetary focus; no exchange of cash could take place in the space. The axes formed by these four examples across time and the city’s geography help to plot out some key social practice coordinates: analysis of economies; the role of class, race, and gender in access to resources; people-centered alternatives to dominant ideologies/methodologies; and the setting/function of making and experiencing art.

Social practice, then, involves a great deal of person-focused social engagement and collaborative problem-solving taken on by artists and non-artists alike within specific communities, and this work can incorporate tools of cultural production even if it does not result in a traditional art product. Chicago artist Nance Klehm combines many disciplines in an immersive life practice that extends to many diverse groups and settings. Locally she offers workshops in urban foraging, teaching people how to identify and prepare wild foods found in feral city-spaces. Motivated by commitment to various overlapping ecologies, including the social, Klehm has worked on agriculture-based projects with Chicago’s Pacific Garden Mission and a project for an autonomous-living system with the Center for Land Use Interpretation on its Utah site. What are the nuances of working in differing capacities and contexts? Klehm elaborates:

I had to loosen my expectations with the Pacific Garden Mission because I was working with homeless people and evangelicals. It was really intense but also easier in some ways because I knew what I was up against since it was always pressing in on me—homeless people, evangelicals, and millions of worms doing their thing . . . whereas [Center for Land Use Interpretation’s] Clean Livin’ is so wide open, where things need to work, but actually don’t. It doesn’t need to have true functionality because it is art; when I work as a tech or as a consultant functionality is expected.

Klehm presents an interesting contrast here, one that invites further questions. Within a social service-oriented social practice—when art happens under the primary aegis of supplying social solutions—specific outcomes are demanded. Their absence equals high-stakes failure. Yet in more open-ended contexts, where the art occurs in the name of socially or ecologically informed cultural experiment, “failure” is not tied to deliverable results. It is a hazier word, and may in fact not be applicable to a truly experimental project.

3. Making Making Happen: Community of/with Artists

When social practice projects are open-ended, long-term, and not driven by specific outcomes, how are they funded and where does the “art” happen? Who makes the art? Who determines its success and/or value? Many of the groups and individuals contributing to Support Networks have engaged these questions in pragmatic and innovative ways. In “Alternative Arts Funding in Chicago,” Bryce Dwyer discusses an array of funding systems created “by people whose view from the ground substituted sophisticated knowledge about their communities’ needs for the deep pockets and infrastructure of conventional funding organizations.” Some of the funding models (Sunday Soup, Peace Party, Community Grant Night at Maria’s Bar) fall under the loose catchword of “crowdsourcing,” while others (Chances Dances, Fire This Time Fund) adapt organizational and operating methods from more traditional granting agencies.

What’s different about all of these is their tendency to erase the social division between grantee and grantor. Another commonality is the commitment to fairness in awarding based on need and on the value of the project. Sometimes funds are generated and passed from artist to artist, not unlike the early 20th century “rent parties” thrown by jazz and blues musicians for themselves and each other. However, funding models like Peace Party, Chances Dances, and the Community Grant Night are potentially limited by their bar-and-club-dependent cash stream. Such systems cut out many potential supporters who, for demographic or other reasons, are unable to contribute to this type of funding despite desire to do so. Alternative arts funding is obviously deeply imbricated with alternative arts spaces, especially because some of the spaces hosting funding parties also host art events.

Access to space for all phases of art projects (including performance and exhibition) is as vital as access to funding. And again, artists themselves have folded the solution to problems of workspace access into their working practices. While perhaps not exactly a form of social practice on its own, the self-provision of workspace and funding is vital for the majority of social-practice artists who have not reached a level of status that makes them attractive to traditional funding sources. Artist-run spaces have always nourished Chicago’s cultural landscape and its cultural producers throughout history, from the South Side Community Art Center to Randolph Gallery to Mess Hall, up through today’s Dorchester Projects, Experimental Station, and Sector 2337.

Often the spaces in which projects happen are not art spaces at all; sometimes access to space comes through partnership with social service providers like Pacific Garden Mission. Other times, the nature of the project itself precludes the use of art-oriented spaces entirely. If urban space itself is the center of the project, then the whole city is the work. Between 2001 and 2004, a collective known as Department of Space and Land Reclamation (DSLR) used tactical media approaches like altered signage, bogus property development, community organizing, and guerilla street performance to highlight and critique gentrification and the lack of public space in Chicago.

4. Conclusion as Threshold: Is This Art? Are We Art?

One interesting fact emerges from intensive reading of Immersive Life Practices and Support Networks: not all those who operate in a social practice milieu are graduates of art schools. Yet a growing number of art schools offer concentrations or course offerings in social practice. Does this mean that traditional art markets and venues are becoming able to metabolize social practice projects, or does it mean that the discipline itself is contributing to ongoing art-world transformations? Probably both things are true, though it’s unclear how social practice projects might function in strictly market terms. In considering such notions we are invited to ask why art really gets made. We may also ask why most people who set out making art (MFA students in particular) are prevented from doing so beyond the art school context by the overwhelming burden of debt, job scarcity, and other social pressures. Additionally, we are compelled to question the appropriateness of the still deeply-entrenched idea of an artist as a single individual who makes highly valued objects meant to be consumed and traded within a rarefied group of privileged people. However we define our relationship to art, social practice discovers meaningful alternatives to the dominant notions of what is possible in life.