Saturday, April 23

Uptown Church

1219 31st Street South, Minneapolis [map]

3:00 pm and 7:00 pm; see below for details

FREE and open to the public!

Join us as two dozen poets from around the country gather to pay homage to one of the greats through talks, readings, stories, films, and even song. Participants include:

Ralph Angel • Betsy Brown • Rob Casper

Dan Chelotti • Gillian Conoley • Christopher DeWeese

Paul Dickinson • Kelly Everding • Dobby Gibson

Matthea Harvey • James Haug • Steve Healey

Richard Jackson • Lisa Jaech • Louis Jenkins

Ben Kopel • Seth Landman • Eric Lorberer

Frances McCue • Emily Pettit • Guy Pettit

Alex Phillips • Bin Ramke • Donald Revell

Eugene Richie • William Waltz

Rosanne Wasserman • Dara Wier

Music by Brian Laidlaw and the Family Trade

Plus the release of a NEW chapbook

of unpublished poems by James Tate!

SCHEDULE

We have so many great poets participating in this James Tate tribute that you have two chances to see them—come for either or both segments.

Afternoon Program 3:00 - 4:30 pm

talks, readings, music and film, with coffee reception

Betsy Brown

Rob Casper

Dan Chelotti

Christopher DeWeese

Kelly Everding

Steve Healey

Richard Jackson

Lisa Jaech

Louis Jenkins

Brian Laidlaw and the Family Trade

Eric Lorberer

Frances McCue

Eugene Richie

William D. Waltz

Evening Program 7:00 - 8:30 pm:

evening talks, readings, music and film

Ralph Angel

Gillian Conoley

Paul Dickinson

Dobby Gibson

Matthea Harvey

James Haug

Ben Kopel

Seth Landman

Brian Laidlaw and the Family Trade

Emily Pettit

Guy Pettit

Alex Phillips

Bin Ramke

Donald Revell

Roseanne Wasserman

local business partners

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Ralph Angel’s latest collection, Your Moon, was awarded the Green Rose Poetry Prize. Exceptions and Melancholies: Poems 1986-2006 received the PEN USA Poetry Award, and his Neither World won the James Laughlin Award of The Academy of American Poets. In addition to five books of poetry, he also has published an award-winning translation of the Federico García Lorca collection, Poema del cante jondo / Poem of the Deep Song.

Betsy Brown is a Minneapolis poet and author of the prize-winning book Year of Morphines. She studied with James Tate at the Iowa Writer's Workshop when he was a visiting professor there from 1986-87.

Robert Casper is the head of the Poetry and Literature Center at the Library of Congress. The founding publisher of the literary magazine jubilat, he has also worked at the Poetry Society of America and the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses.

Dan Chelotti is the author of x (McSweeney’s, 2013) and a chapbook, The Eights (Poetry Society of America, 2006). He teaches English at Elms College and lives in Massachusetts.

Gillian Conoley is the author of seven collections of poetry including Profane Halo, Peace, and A Thousand Times Broken. A recipient of the Jerome J. Seshtack Poetry Prize from The American Poetry Review, as well as several Pushcart Prizes, she is Professor and Poet-in-Residence at Sonoma State University, where she is the founder and editor of Volt.

Christopher DeWeese is the author of The Black Forest and The Father of the Arrow is the Thought, both published by Octopus Books. He is Assistant Professor of Poetry at Wright State University.

Paul D. Dickinson's poetry has been featured in two films: The Last City in the East (2011) and Tired Moonlight (2015) Dickinson teaches in the English Department at Concordia University in St. Paul. He is currently the host of the Riot Act Reading Series.

Kelly Everding received her MFA from the University of Massachusettes, Amherst and has published poems in numerous journals, including Colorado Review, Black Warrior Review, Conduit, Caliban, and Exquisite Corpse. Her chapbook, Strappado for the Devil was published by Etherdome Press in 2004. She lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota where she works for the nonprofit organization, Rain Taxi, Inc., which publishes Rain Taxi Review of Books.

Dobby Gibson is the author of Polar, which won the 2004 Beatrice Hawley Award, as well as two books from Graywolf Press: Skirmish and It Becomes You. His poetry has appeared in Ploughshares, Fence, New England Review, and other magazines and journals. A graduate from the MFA program at Indiana University and recipient of a fellowship from the McKnight Foundation, he lives in Minneapolis.

James Haug is the author of eleven books and chapbooks of poetry, including Legend of the Recent Past, Walking Liberty, Fox Luck, Why I Like Chapbookss, and Scratch. Haug’s poems have appeared in American Letters & Commentary, American Poetry Review, Conduit, Field, Gettysburg Review, jubilat, Open City, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. He’s received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Cultural Council, and serves as an editor for UMass Press’s Juniper Poetry Prize.

Matthea Harvey is the author of Sad Little Breathing Machine (Graywolf, 2004) Pity the Bathtub Its Forced Embrace of the Human Form (Alice James Books, 2000), and Modern Life (Graywolf, 2007), which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and a New York Times Notable Book. Her first children’s book, The Little General and the Giant Snowflake, illustrated by Elizabeth Zechel, was published by Tin House Books in 2009. An illustrated erasure, titled Of Lamb, with images by Amy Jean Porter, was published by McSweeney’s in 2011. Her most recent collection, If The Tabloids Are True What Are You? (Graywolf Press, 2014) combines poetry and visual art. Matthea is a contributing editor to jubilat, Meatpaper, and BOMB. She teaches poetry at Sarah Lawrence and lives in Brooklyn.

Steve Healey is the author of the poetry volumes 10 Mississippi and Earthling, both from Coffee House Press. His essays and criticism have appeared in the Writer’s Chronicle and Rain Taxi, and his poems have appeared in the anthology Legitimate Dangers: American Poets of the New Century and the journals American Poetry Review, Boston Review, jubilat, and others.

Richard Jackson has published over twenty books including thirteen books of poems, most recently Retrievals (C&R Press, 2014), Out of Place (Ashland, 2014), Resonancia (Barcelona, 2014, a translation of Resonance from Ashland, 2010), as well as four chapbook adaptations from Pavese and other Italian poets. He has translated a book of poems by Alexsander Persolja (Potvanje Sonca / Journey of the Sun) (Kulturno Drustvo Vilenica: Slovenia, 2007) as well as Last Voyage, a book of translations of the early-20th-century Italian poet, Giovanni Pascoli, (Red Hen, 2010) and edited books of poems by Slovene poets Tomaz Salamun and Iztok Osojnik. In addition, he has edited the selected poems of Slovene poet, Iztok Osijnik. He was awarded the Order of Freedom Medal for literary and humanitarian work in the Balkans by the President of Slovenia for his work with the Slovene-based Peace and Sarajevo Committees of PEN International. In 2009 he won the AWP George Garret Award for teaching and writing.

Lisa Jaech is a Seattle based artist and animator. She started reading James Tate in the 8th grade when she was assigned to select and read poetry aloud to her English class. Her classmates thought Tate's poetry was pretty weird, and she was thrilled by that. Besides animating to poetry, she loves combining documentary and animation. She graduated in 2015 from California College of the Arts with a BFA in Animation.

Louis Jenkins has been writing and publishing poetry for more than 40 years Recently, he and Mark Rylance, actor and former director of the Globe Theatre, London, co-wrote a stage production titled Nice Fish, based on Mr. Jenkins poems. The play premiered April 6, 2013 at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis and ran through May 18, 2013. A revised version of the play was performed at American Repertory Theater in Boston (Jan.-Feb 2016) and at St. Ann’s Warehouse in New York (Feb.-March 2016)

Ben Kopel is the author of Victory (H_NGM_N Books). He lives in Austin, TX where he teaches creative writing and composition to junior high and high school students. He reviews books, albums, and shows for FLOOD Magazine, and is currently working on his second full-length collection, possibly titled Sutras of Love & Hate.

Seth Landman has two collections of poems, Sign You Were Mistaken (Factory Hollow, 2013) and Confidence (Brooklyn Arts Press, 2015). He lives in Northampton, MA and watches a ton of basketball games with friends.

Frances McCue is a poet, essayist, and arts instigator. From 1996-2006, she was the founding director of Richard Hugo House in Seattle. She has published four books, including a book of essays about Richard Hugo and the Northwest Towns that inspired his poems: The Car That Brought You Here Still Runs, and two books of poems: The Bled, which won the Washington State Book Award, and The Stenographer’s Breakfast, winner of the Barnard New Women Poets Prize. Her most recent book of prose, Mary Randlett Portraits was released in 2014. Currently, she is working on Where the House Was, a documentary poem and film about the demolition of the Richard Hugo House building in Seattle.

Emily Pettit is the author of Goat in the Snow. She is a writer, visual artist, teacher, and an editor for Factory Hollow Press and jubilat. She teaches at Columbia University.

Guy Petitt was the director of Flying Object Press until 2015. Currently, he is pursuing a Masters degree for graphic design at Rhode Island School of Design.

Alex Phillips is a senior lecturer and director of University Summer Programs at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Since the fall of 2013, he has been a faculty-in-residence in the Creative Expressions learning community. His poetry and translations have appeared in journals such as Poetry, Open City, and jubilat, and in Ted Kooser’s newspaper column “American Life in Poetry.” He is the author of CRASH DOME (Factory Hollow Press) and Unkindness (H_NGM_N Books).

Bin Ramke intended to become a mathematician, but studied literature at LSU and eventually received a Ph.D. from Ohio University where as an assistant on The Ohio Review he transcribed an interview with James Tate. He taught in Georgia, now teaches at the University of Denver and sometimes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His most recent book, his twelfth, is Missing the Moon (Omnidawn, 2014).

Donald Revell is Professor of English & Graduate Studies Director at UNLV. Tantivy is his twelfth poetry collection, published by Alice James Books. Donald Revell's previous translations include The Illuminations by Arthur Rimbaud, and A Season in Hell by Arthur Rimbaud, both of which were published by Omnidawn. A Season in Hell won the PSA translation award. His books of essays include Invisible Green: Selected Prose, published by Omnidawn. He is a poetry editor for Colorado Review and lives in the desert south of Las Vegas with his wife, poet Claudia Keelan, and their children Benjamin Brecht and Lucie Ming.

Eugene Richie is the author of

Moiré (Intuflo Editions, 1989),

Island Light (Painted Leaf, 1998), and—with Rosanne Wasserman—

Place du Carousel (Zilvinas and Daiva Publications, 2001) and

Psyche and Amor (Factory Hollow, 2009). His translations include stories by Matilde Daviu and Jaime Manrique’s

My Night with Federico García Lorca (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), a Lambda Literary Award finalist. With Wasserman, he has edited John Ashbery’s translations from the French—most recently, Pierre Martory’s

The Landscapist, a London Poetry Book Society Recommended Translation and a National Book Critics Circle Award poetry finalist; and Ashbery’s

Collected French Translations (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and Carcanet Press, 2014). He is a founding editor of

The Groundwater Press and

Director of Creative Writing in the Pace University NYC English Department.

Photo Credit: Jill Krementz (2013)

William D. Waltz is the author of Zoo Music (Slope Editions) and Adventures in the Lost Interior of America (Cleveland State University Press). His poems have recently appeared in Court Green, Denver Quarterly, jubilat, and Washington Square. He lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota with his wife and children, and is the founder and editor of Conduit.

Rosanne Wasserman’s poems have appeared widely in anthologies and journals; both John Ashbery and A. R. Ammons have chosen her work for the

Best American Poetry annual series. Her poetry books include

The Lacemakers,

No Archive on Earth, and

Other Selves, as well as

Place du Carousel and

Psyche and Amor, collaborations with Eugene Richie, with whom she also runs the Groundwater Press. She’s been teaching sailors at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy for the last twenty-five years. See

http://groundwater-zanne.blogspot.com. On Tom Weatherly, visit

HERE.

Dara Wier's books include Remnants of Hannah, Reverse Rapture, Hat On a Pond, and Voyages in English. Among her works are the limited editions (X In Fix) in Rain Taxi's Brainstorm Series, Fly on the Wall (Oat City Press), and The Lost Epic, co-written with James Tate (Waiting for Godot Books, 1999). Her poetry has been supported by fellowships and awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Massachusetts Cultural Council, and the American Poetry Review. Her work appears in American Poetry Review, Boston Review, Conduit, Denver Quarterly, The Fairytale Review, Hollins Critic, and jubilat, among others.

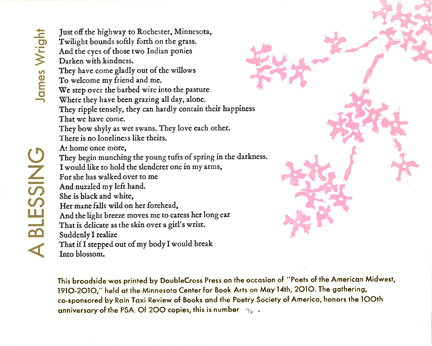

For most of us, war exists in our minds as something far away. We hear things, terrible things, but they’re always secondhand, diluted by geography and reporting and the simple fact that for over a decade now, our country has been vaguely and continually “at war.” It’s no longer new, to the point that it’s practically tedious to think about. War has shifted from a terrible finite event to a national state of being.

For most of us, war exists in our minds as something far away. We hear things, terrible things, but they’re always secondhand, diluted by geography and reporting and the simple fact that for over a decade now, our country has been vaguely and continually “at war.” It’s no longer new, to the point that it’s practically tedious to think about. War has shifted from a terrible finite event to a national state of being.

Unless you were on your ninth straight hour of bingeing the newest Harry Potter book your parents probably didn’t need to demand that you put a book down and do something worthwhile. Reading, we can all agree, is worthwhile; it’s a direct interaction with a piece of art, or an entry point to new ideas or perspectives, an expansion of our minds and imaginations, and often all of the above. It is “good for us.” Films and television shows occupy a similar cultural space, with obvious caveats regarding artistic quality. From these perceptions come the markets for reviews and academic criticism, and the whole bevy of ways we make art a part of our cultural conversation.

Unless you were on your ninth straight hour of bingeing the newest Harry Potter book your parents probably didn’t need to demand that you put a book down and do something worthwhile. Reading, we can all agree, is worthwhile; it’s a direct interaction with a piece of art, or an entry point to new ideas or perspectives, an expansion of our minds and imaginations, and often all of the above. It is “good for us.” Films and television shows occupy a similar cultural space, with obvious caveats regarding artistic quality. From these perceptions come the markets for reviews and academic criticism, and the whole bevy of ways we make art a part of our cultural conversation. Here’s a question the public typically reserves for our pop artists and athletes: how do we expect our writers to behave? My initial answer would have been, well, nothing; I don’t look for anything from a writer outside of his or her work. But just as this isn’t true when Americans talk about rap stars and football players, it’s not quite true for our Great American Novelists and Poets, either. Readers love a good eccentric; we want our writers to act up a little bit, to display the unique mind that created a book we love—but not too much. It’s why we love a good artist biography: we can look at a writer’s life and roll all the weirdness and repellent behavior into a persona that becomes as noteworthy a contribution as any book the author writes. Think of what you love about Hemingway, or Virginia Woolf. How quickly does your mind turn from their books to the person? Same with Salinger or Harper Lee, both of whom are intriguing because of how little we saw of them.

Here’s a question the public typically reserves for our pop artists and athletes: how do we expect our writers to behave? My initial answer would have been, well, nothing; I don’t look for anything from a writer outside of his or her work. But just as this isn’t true when Americans talk about rap stars and football players, it’s not quite true for our Great American Novelists and Poets, either. Readers love a good eccentric; we want our writers to act up a little bit, to display the unique mind that created a book we love—but not too much. It’s why we love a good artist biography: we can look at a writer’s life and roll all the weirdness and repellent behavior into a persona that becomes as noteworthy a contribution as any book the author writes. Think of what you love about Hemingway, or Virginia Woolf. How quickly does your mind turn from their books to the person? Same with Salinger or Harper Lee, both of whom are intriguing because of how little we saw of them. “When the president of the most powerful country in the world doesn’t need to care what the facts are, then we can be sure we have entered the Age of Empire.” This is Arundhati Roy, as quoted in a 2014 Rain Taxi review of Joseph Hutchison’s poetry collection Marked Men. The “facts,” as they relate to the Hutchison poems, concern the racial prejudice surrounding the infamous Sand Creek massacre, which Hutchison takes as his subject. This event took place in 1864, but the racial undertones of the tragedy and the concurrent ignoring of “facts” feel familiar enough to have happened this year.

“When the president of the most powerful country in the world doesn’t need to care what the facts are, then we can be sure we have entered the Age of Empire.” This is Arundhati Roy, as quoted in a 2014 Rain Taxi review of Joseph Hutchison’s poetry collection Marked Men. The “facts,” as they relate to the Hutchison poems, concern the racial prejudice surrounding the infamous Sand Creek massacre, which Hutchison takes as his subject. This event took place in 1864, but the racial undertones of the tragedy and the concurrent ignoring of “facts” feel familiar enough to have happened this year. It’s never been simple for Americans to picture Russia. One second we’re thinking of it warmly as a key ally in the Second World War, and an instant later it’s the frosty enemy in the Cold War. The Soviets are the opposing team in our country’s sports contest, the bad guys in our favorite spy movies; and yet Russia has also given us writers like Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and Chekhov, authors American book lovers can’t get enough of. We cringe at images of Russian citizens waiting in line for goods; we simultaneously demonize their leaders and police. An episode of Family Guy once famously depicted the entirety of Russia’s citizens as bears in hats on unicycles.

It’s never been simple for Americans to picture Russia. One second we’re thinking of it warmly as a key ally in the Second World War, and an instant later it’s the frosty enemy in the Cold War. The Soviets are the opposing team in our country’s sports contest, the bad guys in our favorite spy movies; and yet Russia has also given us writers like Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and Chekhov, authors American book lovers can’t get enough of. We cringe at images of Russian citizens waiting in line for goods; we simultaneously demonize their leaders and police. An episode of Family Guy once famously depicted the entirety of Russia’s citizens as bears in hats on unicycles.