On March 30, 2020, I am breastfeeding a baby in a darkening room and looking at my phone. I have a WhatsApp message:

Clap for #SGUnited: From your windows, doors and rooftops for the doctors, nurses, carers, emergency services, delivery workers, warehouse workers, cleaners, supermarket staff and everyone else keeping Singapore safe and stocked at this time.

My partner and I each lug a child onto the porch. For a moment I think it will just be us, two foreigners clapping into the quiet night, surrounded by unlit windows. But it has already begun—not stadium clapping, not knee-knocking, but not embarrassing. Dark figures in bright windows clapping, trailing off and then starting again, and I try to clap around the balancing baby and think, What is this, what is comparable to this experience? It’s not something in my past; it’s something from a shadow memory, an atemporal sense of collectivity and the tenuous threads that lead from our hands to another figure’s across the flowering yellow-flame treetops, to another in the building beyond, to a cluster of figures at the railing of the parking garage, to the flashing phone light of the condo towering above—we can see this scene, imagine it out the windows of cities we’ve never visited, imagine it over decades down history’s deep well. We are listening for small auditory circuits, for clapping as both interruption and continuance. Until like fat drops wind-shaken from tree leaves after a rain, it stops. We stand there for a few minutes more, watching as the other dark figures slowly turn back to dishes and children’s bedtimes. I am grateful and furious: can this clapping initiate hazard pay? Can this clapping manufacture ventilators?

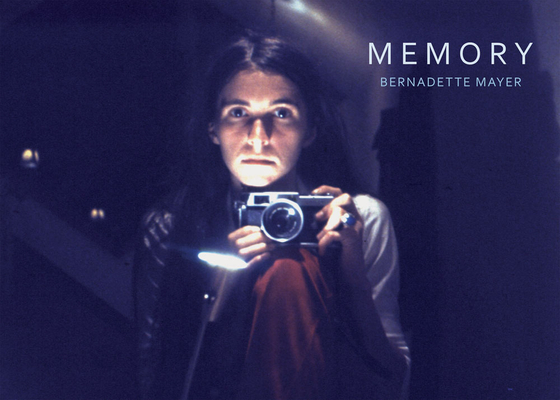

According to the official count, coronavirus appears in Singapore on January 23. Through March, the government implements various public health measures, including the distribution of masks. On March 18 I receive Bernadette Mayer’s Memory (Siglio Press, $45) in its new edition published by Siglio Press. A stay-at-home period called the Circuit Breaker begins April 7. The new edition is a 10 by 7.5 inch hardcover with glossy pages interspersing photo grids, single-frame enlargements, and text—a deeply satisfying visual and tactile object. And after it arrives in Singapore I can barely open it. So lost so you’re lost how lost can you be when everywhere you turn it’s morning & a flag’s going up over a map . . .

Memory has threaded through my life these past five years, but my previous encounters with it occurred when I was nearer to the Mayer who made it, both of us younger and aspiring Art Monsters (to borrow a phrase from Jenny Offill), fascinated by photography. Memory began as a 1972 installation of over 1,110 photos—one roll of slide film taken per day for the month of July 1971—and six hours of accompanying audio recordings. The edited audio was published as a book in 1975 by North Atlantic Books. Then the project became spectral: for a while Mayer’s work continued in Memory’s conceptual mode, and she wrote a short, related piece in 1989, but the book was out-of-print and the pictures in storage and archives. An excerpt of the work was exhibited at a 2008 conference in Orono, Maine. I began writing about it in 2015, and for a while I walked around Chicago saying that the installation should be restaged, until Jennifer Karmin and Fred Sasaki facilitated its showing at the Poetry Foundation in 2016. In 2017, pregnant and on unofficial bedrest in Beijing, I took many Memory-esque photos of tea cups in a fit of loneliness and frustration at not being able to see the work in its newest-oldest iteration; the original photo boards, with the audio, were reinstalled at the Canada Gallery in New York, and the slides were projected at New York’s Museum of Modern Art at an event in 2019.

Siglio’s edition of the book is unprecedented in uniting the photographs and text for the first time. But now in the Circuit Breaker, though I wish every day that I could gather all the poignancies of my life to myself, I want to do so in a way that has little to do with my actual memories. And so I don’t want to remember Memory and I don’t want to remember my previous engagements with it. I’m not interested in rabbiting down a personal memory hole. Luckily, neither is Memory. It’s a book that constantly bristles against its commitment to comprehensive documentation, and when, at the beginning of April, I finally do open it, I am surprised by how little of its contents I remember. Have I even read it before?

This time through I am drawn to the text’s gestures of collectivity. In various moments, Mayer transcribes conversations with others about the work, or describes the film production: . . . & he says do you have any memory this time at all & I say not so far & he says you will I think . . . If we had to do a plot summary of Memory—even though attempting to do so is as absurd as being told to put a rather large lake in a cup—we would say that much of the book involves the making of a film and features many artist compatriots, sometimes marked by name and sometimes by initial; these people are whirling and recurrent entities, not generally still enough to come into view as characters. To put it differently, we could say that while the work is a massive experiment in documentation, its intimacies are still out of reach, the actions emphasized. We stopped at another gas station about halfway up for coffee, remember? The collectivity is in the motions and the process. In my view, the project isn’t attempting to inhabit collective memory—Memory doesn’t suggest that subjectivities are shared to that degree—yet there is a common reverberation in forgetting.

Reading the book in the Circuit Breaker is often uncanny: . . . the house is dark it’s strangely quiet maybe I dont know how to work anymore: when you awake you will remember everything. . . . I’m itchy I’ve lost my memory I’ve lost my money in a minute. . . . & think about memory with fear, too much time went into the windows, we saw it, so stretch down, a new sign, save it, it’s needed, use it, it’s thrown, throw it & so on, safer at distances, come over here, where were worrying where were time . . . The text is difficult to hold with attention; it almost asks you to drift away, and the photos sometimes bring you back to it and sometimes cast you further out. I seemed more real yesterday to see day today as a form a triangle . . . There are the thoughts you think while reading the book, and that seems to be much of the point.

It’s not the book’s snapshot portrayal of domestic scenes or the everyday that produces this quarantine uncanniness: it’s the weird looping it does with time, clinging to and mucking up seriality, and how the pictures run parallel and at a remove, like old pictures you find while cleaning the house and can’t remember taking. July 20 includes double-exposures, a day of specters. These figures have made the circuit back, which is the anxiety of photography. They are marked as already-past, they are a way of visualizing the present that literalizes its ephemerality. It’s me, we think. I remember how I felt, a few months postpartum, when a nurse looked at my partner standing next to me and said, Where’s the mama? Our circuits leaving trails of light at the expense of our presents. . . . some memories qualify where the present endures not for a minute or an hour or a day but for weeks & months & years . . . We mourn in our temporal unmooring, afraid that the hiccupping, often-stagnant present will never be released into free movement again.

What circuits of movement are possible in the Circuit Breaker? Figurative roads, journeys, detours: literal, the lack thereof. There are circuits as in revolutions of suns and planets, circuits of time traced out. There are circuits of exercise, circuits of streaming movies. Of course there are circuits of electrical current, which circuit breakers interrupt, and the nestled circuits as brain synapses, the ways electricity runs around brains and computers: One day the toddler yells Dinosaurs have brains! over and over at bedtime, caught in several circuits. To circuit as to compass in thought, the thoughts you think while reading.

And again those circuits of attention, of paying attention and releasing attention and forgetting to pay attention in a time of waiting. I read an entry of Memory each night. Even this bit of routine is uncertain—I keep thinking I’ve forgotten my reading. Did I skip a day? Do I skip today? Often I haven’t, the days are just long. The relief when the atmosphere changes: now it’s raining. The tempo of the everyday gone off the rails: today was an eternity. Or: what even happened today? . . . a false perspective like memory laughs at the intuition of time: beyond its borders extends the immense region of conceived time, past & future, into one direction or another of which we mentally project all the events which we think of as real & form a systemic order of them by giving to each a date . . . For me, the present is also an amplification of my recent everyday—I have been on maternity time in a country that is new to me, largely at home. I say this not to minimize the differences between maternity leave and stay-at-home orders, for they are substantive, but to explain that my days and feels were doing this before, but less. It’s really raining now and everyone else is asleep and I want to sit and be alone. The quirks of idiosyncratic time, its druggy blossoming and tightening, bottlenecks and streams and all that, are coming to the front.

. . . what can a diary be not a reconstruction, something put in, use the time, pass it, stain it, pass it, it’s stained, it’s magnified, it sticks, it sticks in my mind & my hand always hurts always hurts still does when I write in this book: book, took three rolls to be developed into seen. Some place, something to drink to change my whole way of feeling & something to read, transform, transform translate transmute transcribe transfer transfuse, transform, chamomile does it make a difference? Everyday, I’m saying there are no days, of, we’ve made too much of days and, thinking & write another way . . .

Memory keeps tumbling into lists as a literary technique. Organized by the day, its realism resides partly in uneven daily duration, each dated piece of text a different length, ballasted by a fairly predictable number of photos. On April 11 we take a night walk. I only remember the date because it is a birthday. . . . & that was the night we stayed up all night willow trees waving doors slamming them some days are longer than others & someone says it might take a while it might have some value . . . I am in the Circuit Breaker with wildlings, I mean small children, which is a great pleasure but also when I step into an empty room or out onto an empty road at night a vice releases a grip on my skull. My temporal desires are all postpartum and Circuit Breaker confusion: faster please, slower please. Memory and the Circuit Breaker share an uneasiness with the day’s sudden reign. . . . a day is over another one begins exactly as it happened so let’s pool all our mysteries into one great mystery and I dont remember this at all at all . . . Oh fickle unit of the day, you syncopated slough, you slippery dream, you field of sand. Sometimes wading through you feels like trying to dry off in a sauna. You turn brittle and hollow in accumulation; we stack you carefully and then a gust comes along and scatters you about.

Mayer has said that she wrote Memory against Gertrude Stein’s continuous present and the idea that you can’t “write remembering,” but the text knows that Stein might be right, that in writing past-as-present the presents bleed all over the room and we can’t figure out which one is wounded. The concept isn’t the problem, the “data” is (. . . this is a conceptual piece lacking conceptual data . . .)—there is so much data and we’re always overloaded and forgetting it and arguing about it. Sleep training my daughter one night, I say, I feel like we’re breaking a horse, I keep seeing an animal thrashing against increasingly small circles, but then she falls into sleep, and when we wake I can’t remember how much she cried. Did we give her what she needed? Where are the handmade masks most needed? Listen, I don’t know what to say about getting through this time, this present that exposes the precarities of our movements and routines and is ripping great gashes through some people’s lives. You’ve already read all the articles. We’re breaking circuits and getting our circuits broken. These circuits are small and large, interior and exterior, a trope that keeps turning into an entire history.

On April 21, Prime Minister Lee announces that the Circuit Breaker is being extended until June 1. He says, “You will naturally ask—where does this lead us? How do we exit from the Circuit Breaker?” Memory doesn’t show an exit, and reading it now also underscores the temporal distance between 1971 and 2020—and other contrasts too. However, it demonstrates ways to willfully engage seriality—chronology especially—even as seriality’s structure becomes a fiction, or just ridiculous. Might as well use the ruler for this, might as well be exact as a calendar like remembering a calendar scares the shit out of you . . . and . . . I thought dusk was morning I thought the esophagus was the glottis . . . and . . . I drew the day up as a series, as a moment in the present, sept 20, & as an action . . . It shows us how to keep making art amidst constant uncertainty about the results. . . . I want to leave this place I want to get out of here . . . & I hate myself for keeping on going as if the production of something out of nothing out of here where there is nothing were worthwhile. Which gets us to the real question of reading it right now: what can be made in the Circuit Breaker, and what is the point? How can one see the structure of the pillow fort when you’re trying to build it in the middle of a hailstorm? What kind of art is necessary right now?

Two weeks after the first instance, the clapping happens again. And then again. Its momentum builds, tentatively. Without advance warning, I am surprised by it each time and each time it is welcome—it reroutes the atmosphere and thus my thoughts, like stepping out of an unnecessarily air-conditioned room. One night I put the baby to sleep and then pick up Memory, only to realize I’d finished reading it the previous day. I am writing and then not-writing and then writing, I am stringing painted pasta necklaces with my child—the book models a process of making that crests between continuance and interruption, a lesson forgotten every day. Together we tug the bead down the piece of twine. A process fills its old bed & then it makes a new bed: to you past structure is backwards, you forget, you remember the past backwards & forget. You have to forget again the question about art’s necessity to continue and/or interrupt the Circuit Breaker. You clap again in gratitude and critique both. You build and rebuild the pillow fort because the child requests it, and you lie down in it, and wake again in another room, on another day.

Editor’s Note: To celebrate the publication of Matthew Rohrer’s new book The Sky Contains the Plans (

Editor’s Note: To celebrate the publication of Matthew Rohrer’s new book The Sky Contains the Plans (