by Kevin Smokler

The work of Anne Fadiman is one of the best rebukes in contemporary letters to the moldy myth that a subject’s size is the best measure of its importance. She first rose to prominence as a journalist via her first book, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, the story of an epileptic Hmong child and her family’s interactions with the health care system in Merced, California, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1997. She’s now equally well known for her two subsequent essay collections, Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader and At Large and At Small, which came out in paperback earlier this year. Those books (compiled from Fadiman’s tenure as a columnist for the now defunct Civilization Magazine and as editor of The American Scholar) do for subjects like libraries, coffee, sleep, and ice cream what M. C. Escher did for the staircase: they take a pedestrian aspect of our lives and gently insist we have more to glean by seeing it in three dimensions.

Anne Fadiman is the inaugural Francis Writer in Residence at Yale University. I spoke with her at her home in Whately, Massachusetts, while her dog Typo dashed around our feet and her teenage son Henry practiced guitar in the next room.

Kevin Smokler: I had no idea you and Wendy Lesser were roommates at Harvard.

Anne Fadiman: We were roommates for two years, my sophomore/junior, her junior/senior. We’d met in the fall of 1970, when I was a freshman, in a very small dorm at Radcliffe that had just gone co-ed the year before. Benazir Bhutto and Kathleen Kennedy were in the same dorm. The housing office at Harvard must have been up to something that year.

Wendy and I had a lot in common. We were both literary. We were both from California. But unlike me, Wendy was a mixture of the keenest intellect and the most appealing verve. She had bright red hair and many freckles. She seemed fearless as she moved through the world. She was interested in urban planning and talked a lot about Lewis Mumford. It wasn’t clear whether she was going to follow the literary path or the urban planning path.

KS: I have the sense from reading Threepenny Review that she’s the kind of reader who would be less inclined to leave muffin crumbs in her books, and you more.

AF: I think that that’s probably right. I remember that when she was a senior, on her one day off between final exams, she read Pale Fire for fun. She also went to graduate school in literature and I didn’t. So I remained a kind of dilettantish amateur and she became the real deal.

KS: Something I’ve always admired about your work is that it treats lighthearted subjects like ice cream and coffee seriously, and yet also treats serious subjects lightheartedly without being dismissive of them. Being someone whose career and public image has been shaped so much by being dedicated to literature, do you feel sometimes that you are called upon to defend a position that is not you—to speak to those bemoaning that literature is not taken more seriously?

AF: I don’t ever feel I have to defend anything. I don’t feel that literature has maintained the place in the world it once had, and I wish that would change, but I’m not sure that bemoaning that fact is the best way to make it change. The best thing you can do is just write as well as you can.

I’m not a polemicist. My first book, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, is the most serious thing I’ve written. The story of Lia Lee and the larger story of the Hmong are authentic tragedies, and I spent a lot of time in tears during the eight years I wrote about them. But despite what they’ve been through, the Hmong themselves have a wonderful sense of humor. Hmong folk tales, even though they’re full of violence and death, are very funny. Humor keeps on poking through like little green shoots coming up through the snow. The Hmong sensibility made me feel it was okay for parts of my book to be comic, even though most of it was sad.

That book ended up saying some pretty strong things—I guess you could call them political statements—about cross-cultural communication. But any good it has done has been more or less by accident, since I had no idea it would ever be read in medical schools and anthropology classes and so on. I was aiming at a general audience—a very small general audience—and I never imagined it would have any influence on anybody.

My essays have had even less lofty aspirations. They’re not written with any grand purpose in mind, they’re written to entertain me. They are a selfish pursuit. For example, I love the essays of Charles Lamb, the great early 19th-century English Romantic writer. A few years ago, I thought: “Wouldn’t it be great if I could spend a couple of weeks doing nothing but reading essays by Lamb and biographies of Lamb?” That wouldn’t feel like work, it would feel like a vacation. Was I thinking, “Charles Lamb is underappreciated and my essay about him will raise his status in the American academy?” Not on your life.

Not all the essays in At Large and At Small are lighthearted. The last essay in the book, about a drowning I witnessed when I was eighteen, could hardly be more serious. But most of the time, my own view of life eventually reasserts itself. And my view of life just isn’t very solemn.

KS: It sounds like a directed form of goofing off.

AF: That’s a very good way of putting it. Essays are a guilt-free way of spending time doing something I really enjoy that otherwise I’d feel bad about because it would take time away from my work. So I simply make it my work. Teaching is another form of play. When I became a teacher, my husband said, “You have such a naturally didactic personality, you might as well get paid for it!”

KS: There’s a wonderful tradition of turning goofing off into achievement in literature. The example that comes to mind for me is George Plimpton.

AF: Of course Plimpton did reportage, not essays. He’d go out and become a football player or professional golfer or whatever for a while, and then he’d write about it. He’d actually do it, whereas when I’m in essay mode, I just read about it.

My information-gathering method is more like making maple syrup. Up here in Western Massachusetts we tap our trees every March. To make one gallon of syrup, you have to gather 40 gallons of sap and boil off 39 of them. My essays are like that. I read and read and collect a ton of material. That’s my sap. Then I boil and boil, and the result is often a very brief piece.

Most of the essays in both Ex Libris and At Large and At Small started out as columns for magazines. Those have to be a set length. It’s like writing a sonnet: it can’t be 15 lines, only 14. I like that sense of constraint. The result is that the essays are dense—not dense as in hard to understand (I hope!), but dense in that a lot of stuff has been boiled out of them. What’s left is the stuff I consider the most fun.

KS: Do you think if you hadn’t had the opportunity to, say, write about ice cream for a magazine, you would have still written these essays and found a home for them afterward?

AF: No. I like to have a permanent, or at least semi-permanent, home. Before I write I like to know who the audience is, when I have to turn in the piece, and when it’s going to get published. Despite everything I’ve said about my work being my play and vice versa, I do find writing difficult in some ways. I’m not one of those people who can be galvanized to action without an external push.

My husband [George Howe Colt, author of The Big House] and I take turns writing. One of us does a book and the other has a job with health insurance. He’s currently writing, and I’m teaching. So during this phase of my life, my only time to write is the summer. By my own choice, though, my main project this summer has been editing the first few chapters of George’s current book. It’s terrific, so I’ve enjoyed that tremendously. We’ve always been each other’s first readers and edited each other’s work.

I consider my teaching, in a way, to be as creative as my writing, just as I considered my editing to be as creative as writing when I was at The American Scholar. During those seven years at the Scholar I wrote the essays that became At Large and At Small, but mostly I was editing. And people were always asking me, “Don’t you miss writing?” Well, no more than I missed editing when I was writing! And now that I’m teaching, that’s what interests me most. At this point, to write one more essay and see it published in a good magazine would be pleasant, but it wouldn’t steepen my learning curve. I’m still learning how to teach, so that learning curve hasn’t yet flattened out.

KS: I get the sense you like to focus on one thing at a time.

AF: I tend to get confused and unhappy when my mind has to focus on many things at once. I like to move in a deep, narrow track in which I can get really obsessed with something and do nothing else. Sometimes I’ll take a detour and look at something by the side of the road, but when I’m writing an essay, it pretty much fills my life.

It’s easiest for me to stay focused at night. All the essays in At Large and At Small—including “Night Owl,” which is about being a night owl—were written at night. When I’m writing an essay, I stay up a little later every night until I’m staying up all night, and then I’m in another zone where the phone never rings and nothing can distract me and all I’m thinking about is, say, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. When I was writing my essay on Coleridge, it was just me and him for a couple of weeks.

KS: Do you feel lucky that your body clock is such that you can work at night and not have it be disruptive to the rest of your life?

AF: I don’t feel lucky that my body clock is out of sync with the rest of the world and out of sync with my family. Life would be easier if I had a more conventional circadian rhythm. I don’t enjoy lying awake all night while my husband is peacefully sleeping.

KS: I’d like to revisit this idea from earlier that many of us who love books and literature walk around with: it’s this idea that there was a time when books were at the center of our culture and of popular consciousness. I’ve always felt like that period of time, despite the romanticism we might have about it, came with certain cultural liabilities which we forget when discussing why things are no longer that way.

AF: Such as?

KS: That those places at the center of our culture were largely occupied by white men of a single class. And the impetus to read a canonical set of books was largely based on a mid-century drive for upward mobility in a hierarchal society that thankfully no longer exists—at least not in the same way.

AF: When I was growing up and becoming a reader, I had no sense of what was going on in the wider culture. I had only a sense of what was going on in the mini-culture of the Fadiman family. Which was exactly what you just described—but in our family, I never viewed it as a downside.

My father was the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, and he was exactly the kind of upwardly mobile person that you just referred to pejoratively. One of his best-known books, still in print, was The Lifetime Reading Plan. Nothing could be more canonical. It was an annotated list of 100 or so classic books written by long-dead white males that you were supposed to read over the course of a lifetime in order to become an educated person. That sounds terribly narrow, but the fact is that if you read and thought about all those books, you would become a well-educated person. It might be nice to read some other books as well to add a bit of diversity to the pot, but it’s still a wonderful list.

I have an older brother who, if anything, is a better writer than I am. He chose not to become a writer and I did. My family’s emphasis on white males obviously didn’t cripple me. In fact, maybe it provided something useful to react against. In the preface to At Large and At Small I quote my father saying that there are few women essayists. Maybe I became an essayist in order to say, “Says who?”

But I always felt encouraged by both my parents to do whatever I wanted to do. And growing up in a house with zillions of books was absolutely great.

KS: I get the sense that, in that house, you were raised with the idea that reading was a tactile, lustful activity.

AF: Oh yes, lustful to the core! My father thought books were meant to be handled. He dog-eared the pages and wrote in the margins. After our parents died and my brother and I inherited their library, it was like hearing a voice from the other side to read the notes our father had written next to passages he particularly liked.

My parents were both professional writers, but they also did a ton of reading for pleasure. My father was a judge for the Book-of-the-Month Club for 60 years. And while I’m sure many people thought of that as a form of selling out, he was sometimes able to identify a great book like Catcher in the Rye or And the Band Played On before it was published, and to help it gain the success it deserved. He wasn’t a snob. He got just as excited about a good thriller or sci fi novel as about a literary biography.

Many people are still excited by reading. So I don’t count myself among those who think that literature is dying in the United States. Your own book [Bookmark Now: Writing in Unreaderly Times] is encouraging—it shows that there are young people out there who will take literature in new directions that I can’t even guess at, many of them Internet-based. This may not be the sort of thing that I would write myself, maybe not even read myself. But it’s going to be vital, it’s going to be exciting.

One example is the blog. At the moment, most blogs are terrible. Of course they’re terrible! The form is in its infancy. People who used to write in their journals are now writing in their blogs, and they haven’t yet learned the art of self-editing. But I think that in future, the blog may become what the personal essay was in the past. And I find that a hopeful prospect.

It’s fair to say that the average American is reading and writing more words a day now than he was twenty years ago. Things that used to be handled by phone are now handled by email. Now everybody knows how to type. In the most basic sense, everybody is writing all day long. So it would be wrong to say that as a society we are sliding toward illiteracy—we’re simply sliding toward a different kind of literacy. I can’t say I like it as well as the old kind, but that’s not the same thing as saying that literacy is dying.

I concede that an electronic book might have certain advantages. The search function might be helpful if you were reading a book without an index. I might appreciate it if I were reading a Russian novel because I can never remember the characters’ names. That said, I love the physical book, and if it were replaced, I would mourn deeply. It’s not going to happen in my lifetime, but I may live long enough to see the writing on the wall, or on the screen. We’d lose a lot. For one thing, you can’t scribble in an electronic book. If I’d inherited a Kindle from my father, it wouldn’t contain his handwriting.

KS: You say in Ex Libris that the best place to read is in bed. I happen to agree, but my body also associates the bed with sleep. So I’m constantly caught between wanting to read more when I’m into a really good book and dropping off to sleep because I’m in bed.

AF: I never feel myself dropping off to sleep because I’m always in bed before I’m sleepy. If George is away and I don’t have to get up to take Henry to school, I’m likely to read until three in the morning. That’s what I call luxury. It’s the literary equivalent of being able to eat an entire pint of ice cream straight from the carton because there’s no one around to say you’re being a pig.

KS: I remember you saying that when both of your kids are in college, you could see yourself doing another heavily reported book like The Spirit Catches You. Do you keep that on the horizon?

AF: Yes, I’ve actually got a topic, which I won’t mention here, on which I’ve been collecting information in a desultory kind of way since 1991. There are also some shorter reporting projects that might take a summer.

I used to think I’d be a reporter forever. I started writing essays during a fragile pregnancy, when I was put on eight months of bedrest. They were the only thing I could write in bed. But even after Henry was born and I was vertical and ambulatory again, all I wanted was to keep on writing them. Essays felt comfortable and natural. I’m not a comfortable or natural reporter.

KS: How come?

AF: An essay is always about something I’m already interested in and already know at least a little about. The path of information-gathering is somewhat predictable. With reporting, the scary and fabulous thing is that you’re in the hands of another human being, and you can’t predict what she’s going to say or do. You don’t know whether she’s going to respond well to you or badly. You don’t know whether you’ve prepared enough, or whether you’ve over-prepared and the interaction is going to be stiff. You don’t know if she will be offended by what you write and if you’ll feel guilty afterward.

Reporting has all the excitement and mess of any human relationship. It could be an interaction as short as fifteen minutes, or it could last for years, as it did when I was reporting The Spirit Catches You. Reporting brings fresh air into my life, it expands me, it makes me a larger person. But for all those reasons, I also find it very challenging.

KS: In looking at your work, I get the sense that you enjoy a topic unveiling itself to you instead of saying, “My next six books will be as follows.” For instance, Spirit came about through a conversation with an old friend and Ex Libris was the product of your tenure at Civilization Magazine.

AF: You’re right, some of my projects have been serendipitous. I got the idea for Spirit from an old college friend who was a doctor in California. The editor of The New Yorker happened to pick that proposal—which was full of mistakes—from the six or seven story ideas I’d sent him. Before the piece could run, the editor was fired. I ended up turning the piece into a book so at least it would be published somewhere. In other words, I didn’t plan that book—it happened to me.

But sometimes I do plan ahead. I have folders in my office in which I jot down ideas I want to write about. When I have a column or regular gig, I’m always filling those folders with ideas for future pieces. I clip things and print out stories from the web. When a folder achieves a certain girth, I know its pregnancy is nearly full term. At that point all I need is ten or twelve days of reading and note-taking, and I’m ready to write.

I may plan ahead before I write, but when I’m writing I focus only on the present. Of course, since I’m a parent, I can never devote all my energy to what I’m writing—and thank heavens that’s the case! I had my first child at 35. I’d been writing for a lot of years before then. But when I reread the earlier stuff, it just doesn’t have as much depth or focus as what I’ve written since I became a parent. I learned that every minute counted. I had to stop procrastinating. A day I could devote to writing was a gift I wanted to be sure I used well.

KS: I read somewhere that William Carlos Williams used to scrawl his poems on prescription slips between visits with patients and remained a physician his whole life. There’s something about that pressure that compels us to a kind of greatness.

AF: “Greatness” is hardly the right noun in my case, but that everyday pressure has certainly compelled me to a higher level of intensity. That’s not the only thing that a family gives you. Falling in love, marrying, and having two children have shoved me more fully into the tide of humanity. That doesn’t mean you can’t write well if you’re single and childless, but I’m certain that in my case, marriage and children have made a better writer.

KS: In thinking about the role literature played to your father’s generation, it served not only as a tool for social advancement but also as an object of lust, of pleasure. It was both functional and hedonistic. Somehow, as a culture, we’ve split those two things: the pleasure we get from reading is somehow divorced from the good it might do us. The thing I admire about your work is it seems to bring those two things back together.

AF: It delights me to hear you say that because it’s an idea I introduce to my students on the first day of each of my classes. I tell them: “The purpose of this class is to erode the line between ‘Ought’ and ‘Want.’”

Here’s an example: One of my classes is called Writing about Oneself. Each week we read two first-person works on a given theme, and then the students write on that theme. In the Angst week we read a section from John Stuart Mill’s autobiography about the nervous breakdown he had at age 20, and then we read Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation about the breakdown she had at 20. Mill and Wurtzel sit together on my students’ bedside tables that week. They’re peers. I don’t want my students to think that Wurtzel is “Want” and Mill is “Ought.”

I emphasize this sort of thing in my classes because that’s the way I live. My bedside table is the strangest jumble of everything from crap magazines to Dickens.

KS: I think that portends a very bright future for the written word.

AF: As if I were in charge!

Click here to purchase Ex Libris at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase At Large and At Small at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Winter 2008/2009 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2008/2009

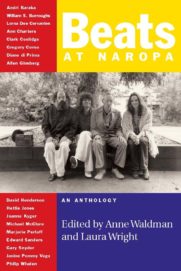

Edited by Anne Waldman

Edited by Anne Waldman