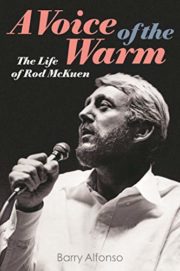

Barry Alfonso

Barry Alfonso

Backbeat Books ($29.95)

by Walter Holland

Singer-songwriter-poet Rod McKuen was a strange, self-conflicted, and tragic figure; an artist of frenetic creativity, he was also a closeted gay man who became trapped in his illusory pop persona as a mellow, lovelorn, balladeer and bard. His complexities do not lend themselves to easy narrative, and his tendency to embellish or outright lie, not to mention his frequent pandering for his own commercial self-interests, leaves one on unsteady ground when trying to explain all of his contradictions. Toward this end, biographer Barry Alfonso tries to separate fact from fiction, and to point out McKuen’s many irregularities, with mixed results.

Alfonso chalks up this obsession with popular acceptance, success, love, and adulation to McKuen’s illegitimate birth, unknown and absent father, and hardscrabble adolescence. This may be indeed one thread of the story, but Alfonso tends to play more partisan sleuth than impartial biographer; the scant facts of McKuen’s childhood create an invitation for subjective overreach. Worse, Alfonso sometimes fails to read his own unearthed clues, and falls into acting as a defender, publicist, and enabler for McKuen; he ends up besting the “King of Kitsch” at his own game by claiming him as a pop music innovator, populist poet, almost messianic icon, and mainstream entertainment Svengali.

In essence, McKuen’s tale is one that stakes familiar ground in American pop culture: the impoverished dysfunctional roots, the determined rise to towering fame, and then the slow slide into an inglorious end, which in McKuen’s case even includes self-imposed isolation within a once-luxurious mansion. This is in some ways a cautionary tale of how an abused kid struggles to play David in the face of numerous Goliaths: snobbish, pretentious critics; crass recording and publishing managers, agents, and handlers; and liberal-minded effete hypocrites who we are told hated or envied his brand of populist sentimentality and Middle-American appeal. Even gay activists who sought to “label” McKuen as homosexual are excoriated for trying to reign in this free spirit’s fluid and uncontentious nature.

But there are often furtive contradictions in McKuen. Early on, Alfonso tells us McKuen might have attended several meetings of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles, and holds this up as proof of McKuen’s gay activism and lifelong commitment to affirm human sexual rights and espouse a love-for-love’s-sake, inclusive philosophy. But Mattachine was still a closeted organization, one that proposed an assimilationist strategy to recast homosexual men as wholesome, non-threatening Americans. McKuen hardly stays, disappearing after only one or two meetings.

These details of McKuen’s life are indeed fascinating, and they present a poignant, complex, and tender tale of an oddly-overlooked American pop cultural phenom. As such, this book joins the continued revisionist effort to out Hollywood’s gay, bisexual, and queer artists and dream-makers, including gay men such as Mike Connolly, Cary Grant, Rock Hudson, and Henry Wilson. Alfonso’s exhaustive research, merged with his expertise as a music journalist as well as accomplished songwriter, has unearthed an in-depth history of McKuen, his friends, his lovers, and his trail of joy and tears.

But Alfonso’s obsession with defending McKuen and his fervor at disproving elitist criticism forces his narrative into a mire of hyperbole and a repetitive, reflexive pop-psychology, one delivered in easy, single-sentence catch-phrases. Even Alfonso’s “Introduction” to his book seems defensive from the get-go: “Singer-Songwriter-Poet Rodney ‘Rod’ Marvin McKuen (1933-2015) is arguably the most successful popular artist of his time who has never had a biography written about him. Why?”

This aggressive rhetorical question, one supposes, is used to pique curiosity and draw us into the rest of the book. But after a brash listing of McKuen’s many claims to fame, we are told of the legions of critics who refused to “concede that this ‘King of Kitsch’ had an outstanding talent for anything except fleecing his customers.” Dick Cavett, Karl Shapiro, and Nora Ephron are all implicated as having cast Rod as a “clever hack, who cranked out treacly songs and superficial poems as if they were Hostess cupcakes, with utter cynicism.” Alfonso continues by suggesting they felt McKuen’s “sensitive-poet act was a con, a snare for the mentally lazy and the aesthetically stunted.” Then he writes:

This last line of thinking is important to note, because these critics looked down upon not only McKuen but his audience as well. That anyone would lap up such cloying pap was prima facie evidence of Middle American mediocrity. That these fans seemed to worship Rod as something more than an entertainer and writer of greeting-card verse only reinforced their indictment.

Harsh words indeed, and ones bearing a resentment that seems to be more rooted in 2019 Trumpian rhetoric than in good journalism. McKuen’s life was indeed veiled in braggadocio and a manic, impulsive work-drive; his output of songs, poems, and merchandising was spectacular, but so were his failed schemes, projects, and relationships. Alfonso’s defensive posturing and frequent editorializing seem to prevent him from seeing the clear and troubling signs of falsity and rampant commercialist opportunism in his subject. When they come up in the narrative, time and again he easily attributes them to familial upset, the absent father, the mean bi-coastal elitists, and overly-ironic leftists. There is a sense of protection and fealty to McKuen’s memory that feels oddly out of place, and that impairs what is otherwise a useful and interesting biography.