by Brian Evenson

by Brian Evenson

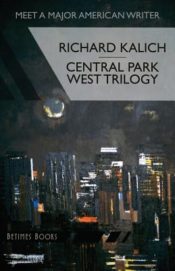

Richard Kalich has been a finalist for the Pen/Faulkner Award, a winner of the New American Award, and a nominee for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. His second novel, The Nihilesthete (Permanent Press, 1987) was declared “one of the most powerful books of the decade” by the San Francisco Chronicle. Narrated by a caseworker obsessed with a quadriplegic who becomes his ward—and whom he alternately tries to help realize his artistic ambitions and to destroy—it is the first book in Kalich’s Central Park West Trilogy, which also includes Charlie P (Green Integer, 2005) and Penthouse F (Green Integer, 2010), both of which take up the investigation of the relationship of life and art begun in The Nihilesthete. In Charlie P , which Sven Birkerts calls “delightfully dark, sardonic, playful,” the titular character decides he will be able to live forever by not living at all, by living only in his mind. Penthouse F ups the ante by including a character named Kalich, and the metafictional novel—which American Book Review called “akin to the best work of Paul Auster in terms of its readability without sacrificing its intelligence of experiment”—is about both his novel in progress and the death of two children in his apartment.

Kalich’s latest novel, The Assisted Living Facility Library (Green Integer, $19.95) is also about a character named Kalich (perhaps the same Kalich, perhaps not) as he simultaneously works on a novel about a young boy and his schizophrenic mother and prepares to go into an assisted living facility, a prospect which requires him to narrow his library to 100 books. In a blurb on the back, Brian Evenson calls it “experimental fiction at its best and most human”; I (perhaps the same Brian Evenson, perhaps not) interviewed Kalich to plumb this thought a little further.

Brian Evenson: You've published five novels. The last two in particular have a metafictional quality, and seem at times to be drawing on, or commenting on, your own life—Penthouse F for instance, has a writer named Richard Kalich in it, as does The Assisted Living Facility Library, which also incorporates photographs, letters, and emails from the actual Richard Kalich's life. What's your sense of the relationship of fiction to life, and how has it changed as you've moved forward in your career? Has exploring that relationship become more important to you as you've aged?

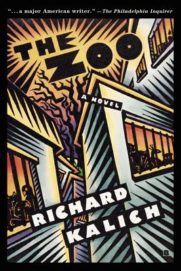

Richard Kalich: Fusing fiction and life has become one of my major concerns in recent fictions—but that statement deserves context. My first novel, The Zoo, was an allegory taking place in Animal World. Its concern was the loss of inner life in our human world and I dramatized this by having animals expressing inner life being zoo'd by the nefarious tyrant leader of Animal World. By the end of the narrative, hardly was there a bird left that soared much less flew; all animals knew their place and stayed on the ground or below.

Next came The Nihilesthete, where I depicted a man with no body, no mind, no language except a cat's meow, and showed this person to be an artist, possessing the most significant dimension humans can have, spiritual fecundity, and which I felt our world was fast losing. I paired my character, Brodski, against his arch enemy, Haberman, a dried up civil servant who never realized his existential possibilities and for whom Brodski serves as a mirror, revealing to him all he was not.

Eighteen years later I found the courage to write my next novel, Charlie P . That post-modern comedy represents my turning point as a novelist; my coming to grips with the limitations of language and traditional narrative ploys such as plot, coherence, continuity.

Penthouse F followed. Though the metaphoric image came to me the day I finished writing The Nihilesthete, I didn't find the courage to write the novel for another twenty years. Penthouse F allowed me to incorporate concerns that still obsess me today, and that, as you say, readers will find in The Assisted Living Facility Library. The fusion of art and life. Indeed, my narrator's name, Richard Kalich, demonstrates this unbending linkage in extremis. Penthouse F's central concern is how the Image has usurped the Word and in so doing has diminished our sense of self even further. The narrative shows Kalich unable to distinguish between the real and the images he sees on screen, of a boy and girl, and how he lives his life as a voyeur, in his mind—along with the attendant dangers of doing so.

Penthouse F followed. Though the metaphoric image came to me the day I finished writing The Nihilesthete, I didn't find the courage to write the novel for another twenty years. Penthouse F allowed me to incorporate concerns that still obsess me today, and that, as you say, readers will find in The Assisted Living Facility Library. The fusion of art and life. Indeed, my narrator's name, Richard Kalich, demonstrates this unbending linkage in extremis. Penthouse F's central concern is how the Image has usurped the Word and in so doing has diminished our sense of self even further. The narrative shows Kalich unable to distinguish between the real and the images he sees on screen, of a boy and girl, and how he lives his life as a voyeur, in his mind—along with the attendant dangers of doing so.

In The Assisted Living Facility Library, I went even further, hardly distinguishing between character and narrator, both deemed Richard Kalich; I made every effort I could to show Kalich's life's concerns and the narrator's fictional concerns as one. His love of books, his constant questioning to understand and transcend his mind/body split. Why can he write so subversively, create such demonic characters, and yet only live his life timidly, bookishly, in his mind? Or, as his twin brother lambasts him almost daily, live only half a life. Approaching the end of the novel I had no idea how to end it—and then I had a dream, and fortunately I had the writer's instinct to follow the dream. The dream allowed me to achieve something that was heretofore existentially impossible. It allowed me not only to dramatize this author's most vulnerable and human side, but also to resolve and transcend my own mind/body split.

BE: One of the other impulses I see in your later fiction is a kind of stripping down. You have an ability to make the most of small gestures, to see what you can do without and still have a satisfying piece of fiction. I see that in David Markson's late work as well: a careful focus on details that most other writers might not even think to mention and a disregard for most of the things that people think fiction should do: plot, for instance. There's not a plot in the traditional sense in The Assisted Living Facility Library—or if there is, it's very attenuated. And yet we learn a great deal about this character through the very simple but humane act of him thinking about the things, books in particular, that surround him.

RK: Yes, I agree. And all that is designated by my mantra: “Words are the enemy of Writers.” Or perhaps more particularly in our life experience: Words have become the enemy of Writers.

BE: Can you talk a little more about that? Writers, of course, have to use words, which may mean that the act of writing always risks consorting with the enemy. How does one use words without being used by them? And what, as a writer, do you hope to use them for?

RK: In my youth, ages seventeen to twenty-two, I revered Thomas Mann. I must have read everything he wrote or that was written about him. And when I wrote my first novel at age twenty-six, it was only logical that I write it in the High German style that Mann had mastered. However, I had the proverbial “rude awakening” when my twin read my manuscript and said: “This is the worst piece of self-conscious, constipated shit I've ever read in my life.” It took another fourteen years for me to write my first published novel, and to write it in my own voice. With a sense of levity today, I can say I blame Thomas Mann for costing me all those years. But more honestly it was my nature—a near-fatal belief system that believed in the Absolute, raised The Word to the transcendent realm.

Once published, I commenced to repeat the phrase to all who would listen, mostly writer friends. Most scoffed, some smiled ironically, but had little or no idea what I meant.

As the years progressed, my use of words became less rather than more. Instead of obsessive modernist detail and the omniscient narrator, I turned to metafiction. I honed in on clarity, economy, precision, and accountability to not only myself, the writer, but first and foremost to the reader. My mantra became writing is dialogue, not monologue; communal sharing, not self-referential isolationism. I ceased with forced or even purposeful embellishment and poesy.

As the years progressed, my use of words became less rather than more. Instead of obsessive modernist detail and the omniscient narrator, I turned to metafiction. I honed in on clarity, economy, precision, and accountability to not only myself, the writer, but first and foremost to the reader. My mantra became writing is dialogue, not monologue; communal sharing, not self-referential isolationism. I ceased with forced or even purposeful embellishment and poesy.

And now with the digital culture reigning supreme, the image supplanting The Word, Transcendence turning to Contingency, ontology itself (our self-world relationship) destabilized, the Self, interiority, and depth gone or at least attenuated, and without them concentration, books, deep thought, and literary culture fast sinking into oblivion, it seems I was right. Alas, I was right. And so I decided to use words rather than have words use me.

And yet all the above is not to say I love words less—if anything, I love them more. For now each and every word I say means precisely what I mean it to say, or as close to “precisely” as I can get, and I feel I've held up my end of the bargain with the reader, our social contract. More importantly, we both have a chance to communicate and understand each other.

BE: So many people seem to want to see writing as giving you something you can pluck out and use in another context. But if I understand you, you’re suggesting that writing is more like establishing a relationship with a reader.

RK: Yes. The way I understand it, the writer and reader are in the midst of an existential encounter, engaged and open to each other and words are their bridge to reach the other side—the Other Side being mutuality, dialogue, and as close to becoming One as they can get. The writer uses words to cross the bridge to the reader and the reader surrenders himself to those words to cross the bridge to the writer. If the words are chosen well enough, if the bridge is constructed soundly enough, reader and writer have a chance to meet.

BE: I read your books in the order they were published, coming on The Nihilesthete by accident in a little bookstore in Oklahoma in the late ’90s and then reading each book in turn as it came out. With the possible exception of The Zoo, I see all your books as talking to one another, as part of a larger conversation. Do you think reading Penthouse F is likely to change how readers view The Nihilesthete or that The Assisted Living Facility Library will shift a reader’s sense of Charlie P? To what extent is the task of each of your books to complicate our understanding of the books that came before?

RK: I agree, and I would add that the conversations are always a kind of ongoing inner dialogue between Kalich, the writer, and the actual Kalich. Or perhaps another way of viewing them is as a continuum. Since that first novel of mine you read, I've grown, matured, evolved intellectually—even to some small extent emotionally—and I've tried to dramatize these progressions in my various novels. Better yet, these progressions, this continuum, took the liberty of dramatizing itself.

But, still, how much do we really change? My guess is there is always a sense of powerlessness in the ongoing battle of this particular problematic man, Richard Kalich, towards individuation. And so, when past middle age and having tossed away so many years on a self-defeating romance as well as squandering them by not writing, by not living my life to the full, I wrote Charlie P, a novel about a man who lives his life by not living it. This novel shows humor, playfulness, levity, perspective, and distance; and it exhibits, both in form and content, a novelist experiencing a sense of jubilation for having finally set himself (as well as his character) free.

But, still, how much do we really change? My guess is there is always a sense of powerlessness in the ongoing battle of this particular problematic man, Richard Kalich, towards individuation. And so, when past middle age and having tossed away so many years on a self-defeating romance as well as squandering them by not writing, by not living my life to the full, I wrote Charlie P, a novel about a man who lives his life by not living it. This novel shows humor, playfulness, levity, perspective, and distance; and it exhibits, both in form and content, a novelist experiencing a sense of jubilation for having finally set himself (as well as his character) free.

Next came Penthouse F—a novel I couldn't hold in or put off any longer when digital culture and the image were gaining such a foothold in our lives. But look closely and you will see my villainous character from The Nihilesthete, Haberman, transplanted to the author/character Richard Kalich, and who in this now screen-dominated world plays his comparable dastardly games with the boy and girl on screen. So, yes, though there are plot and thematic changes from novel to novel, at their core my books do talk to each other.

As to The Assisted Living Facility Library, my concern was to create an autofiction about my lifelong love of books and my just-as-lifelong terror of art and fear of judgement. But as I've spoken about this book earlier, all I’ll say here is that I hope that dream I had which gave me the ending to my novel is as much a surprise to the reader as it was to its author. Though buried and not to be seen, except possibly as a glimmer, in any of my other books, it’s been inside me; it's been there all the time.

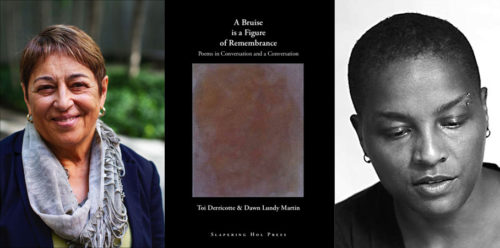

Toi Derricotte is the author of I: New & Selected Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and several collections of poetry, including Tender, winner of the 1998 Paterson Poetry Prize. Her memoir The Black Notebooks (W.W. Norton) received the 1998 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Non-Fiction and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Her honors include the Paterson Poetry Prize for Sustained Literary Achievement, the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, and the Distinguished Pioneering of the Arts Award from United Black Artists. Professor Emerita at the University of Pittsburgh, Derricotte co-founded Cave Canem Foundation (with Cornelius Eady); served on the Academy of American Poets’ Board of Chancellors, 2012-2017; and currently serves on Cave Canem’s Board of Directors, Marsh Hawk Press’s Artistic Advisory Board, and the Advisory Board of Alice James Books.

Toi Derricotte is the author of I: New & Selected Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and several collections of poetry, including Tender, winner of the 1998 Paterson Poetry Prize. Her memoir The Black Notebooks (W.W. Norton) received the 1998 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Non-Fiction and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Her honors include the Paterson Poetry Prize for Sustained Literary Achievement, the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, and the Distinguished Pioneering of the Arts Award from United Black Artists. Professor Emerita at the University of Pittsburgh, Derricotte co-founded Cave Canem Foundation (with Cornelius Eady); served on the Academy of American Poets’ Board of Chancellors, 2012-2017; and currently serves on Cave Canem’s Board of Directors, Marsh Hawk Press’s Artistic Advisory Board, and the Advisory Board of Alice James Books. Dawn Lundy Martin is a poet, essayist, and conceptual-video artist. She is the author of four full-length books of poems: Good Stock Strange Blood (Coffee House Press, 2017), winner of the Kingsley Tufts Award; Life in a Box is a Pretty Life (Nightboat Books, 2015), which won the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Poetry; Discipline (Nightboat Books, 2011); and A Gathering of Matter / A Matter of Gathering (University of Georgia Press, 2007). Most recently, she co-edited with Erica Hunt the anthology Letters to the Future: Black Women / Radical Writing (Kore Press, 2018). Her nonfiction can be found in The New Yorker, Harper’s, n+1, and elsewhere. Martin, a recipient of a 2018 NEA Grant in Creative Writing, is a Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and Director of the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics.

Dawn Lundy Martin is a poet, essayist, and conceptual-video artist. She is the author of four full-length books of poems: Good Stock Strange Blood (Coffee House Press, 2017), winner of the Kingsley Tufts Award; Life in a Box is a Pretty Life (Nightboat Books, 2015), which won the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Poetry; Discipline (Nightboat Books, 2011); and A Gathering of Matter / A Matter of Gathering (University of Georgia Press, 2007). Most recently, she co-edited with Erica Hunt the anthology Letters to the Future: Black Women / Radical Writing (Kore Press, 2018). Her nonfiction can be found in The New Yorker, Harper’s, n+1, and elsewhere. Martin, a recipient of a 2018 NEA Grant in Creative Writing, is a Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and Director of the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics.