photo by Dean D. Dixon

by Allan Vorda

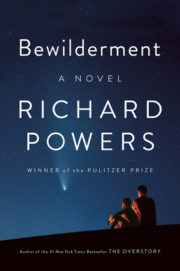

Richard Powers was born in 1957 in Evanston, Illinois, and enrolled at the University of Illinois as a physics major before switching to English as his chosen field. Upon receiving his B.A. and M.A., he moved to Boston where he worked as a computer programmer and a night watchman in a museum, which inspired his first novel, Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance (William Morrow, 1985). After publishing a second novel he moved to the Netherlands, but eventually returned to the U.S. to teach for many years (first at the University of Illinois, then Stanford University) before moving to the Smoky Mountains, where he now lives in nature as he pursues an ascetic lifestyle of reading and writing. Over the years, he has published thirteen novels, typically taking two to four years to write each one. Among his numerous literary awards, he has won the National Book Award for The Echo Maker (FSG, 2006) and the Pulitzer Prize for The Overstory (W. W. Norton, 2018).

As with each of his novels, his latest book, Bewilderment (Norton, $27.95), explores new territory; in this case, the relationship of a father (Theo) and his troubled nine-year old son (Robin). The son undergoes a metamorphosis after participating in an experimental trial called Decoded Neurofeedback. The father, a university teacher and researcher, works on a project that entails creating imaginary planets to which he gives fictional names. Father and son take approximately a dozen visits to these simulated worlds, yet these Planet Seeker visits, in conjunction with the difficulties Theo encounters as a widower raising a son and the effects of Decoded Neurofeedback on Robin, raise the question of what is real and what is simulated. It is an amazing journey that has in-and-out of this world experiences, but perhaps most importantly, Powers does an incredible job of showing the boundless love that a father has for his son. This interview took place over email in May of 2021.

As with each of his novels, his latest book, Bewilderment (Norton, $27.95), explores new territory; in this case, the relationship of a father (Theo) and his troubled nine-year old son (Robin). The son undergoes a metamorphosis after participating in an experimental trial called Decoded Neurofeedback. The father, a university teacher and researcher, works on a project that entails creating imaginary planets to which he gives fictional names. Father and son take approximately a dozen visits to these simulated worlds, yet these Planet Seeker visits, in conjunction with the difficulties Theo encounters as a widower raising a son and the effects of Decoded Neurofeedback on Robin, raise the question of what is real and what is simulated. It is an amazing journey that has in-and-out of this world experiences, but perhaps most importantly, Powers does an incredible job of showing the boundless love that a father has for his son. This interview took place over email in May of 2021.

Allan Vorda: The epigraph for Daniel Keyes’s 1959 novel Flowers for Algernon, taken from Plato, incorporates your title: “Anyone who has common sense will remember the bewilderments of the eye are two of the kinds, and arrive from two causes, either from coming out of the light or going into the light, which is true of the mind’s eye, quite as much as of the bodily eye.” Was Algernon an inspiration for Bewilderment?

Allan Vorda: The epigraph for Daniel Keyes’s 1959 novel Flowers for Algernon, taken from Plato, incorporates your title: “Anyone who has common sense will remember the bewilderments of the eye are two of the kinds, and arrive from two causes, either from coming out of the light or going into the light, which is true of the mind’s eye, quite as much as of the bodily eye.” Was Algernon an inspiration for Bewilderment?

Richard Powers: It’s the touchstone intertext for my novel. Keyes wrote the short story the year after my birth, and the novel version appeared when I was nine—the same age as Robin through most of Bewilderment. I read the story in the sixth grade, when I was eleven, and it settled into a permanent place in my imagination as one of those bedrock fables that helps to explain life.

The story itself is mentioned several times in the course of my novel, and on at least two occasions, it serves to further the plot. I even explicitly reference Algernon’s epigraph, from Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” and as you point out, those words serve as one of the sources of my title. But Algernon is also the inspiration for the science fiction invention that serves as the central plot of the entire novel. Daniel Keyes’s story tells of a cognitively challenged man who, through a breakthrough in scientific technique, is granted intelligence far beyond ordinary human limits. A couple of years ago, when I read about a remarkable new technique called decoded neurofeedback, I instantly thought of using it to tell a similar fable. Suppose researchers perfected an empathy machine that could greatly magnify our ability to apprehend the world through our feelings? What might we humans learn to become? Bewilderment turns the Algernon fable on its head. In place of intellect, it deals in emotional intelligence. It tells the story of a little child, going into the light.

AV: Bewilderment is an extraordinary story of the heartfelt relationship between a father and his son. As someone who doesn’t have any children, how were you able to capture the essence of the feelings of Theo and Robin?

RP: Well, I had a lot of experience being a child. And when I grew up, I began to suspect how my father had been a child once, too. I was also an older brother, with too much parental instinct for my own good. I have been an uncle several times over, and I’ve been a surrogate dad to more than one of my friends’ children. I spent many years as a teacher, in constant contact with lives looking for guidance and direction. I’ve watched almost everyone I’ve ever loved struggle with the unsolvable mystery of how to raise another life. So my own life has been more than full of vicarious parenting.

Children can possess enormous amounts of innate emotional intelligence, but adult pragmatism and practicality tend to wear it down. While finishing my previous novel, The Overstory, I read numerous accounts of the toll our growing environmental catastrophe is taking on the young. I kept running across a recent neologism: solastalgia, the emotional anguish caused by an apprehension of the dying planet. It occurred to me that we were raising a generation of troubled kids, born homesick for a place that they never knew. What would it be like to raise a child suffering from such an illness? I’d never seen a parenting story that addressed that question. So I wrote one.

AV: Early on we learn that nine-year Robin has issues with anger. Is his anger due to his mother’s death? Is there a medical term for what is afflicting Robbie?

RP: So much of the book is concerned with the crudeness and insufficiency of our diagnoses, etiologies, and understandings of childhood neurodivergence. Robin’s behavioral differences go way beyond anger issues. He’s an uncanny child, intense and otherworldly, whose peculiarities prevent his successful integration into the social world. When I was a child (possessing many of these qualities myself), many of Robin’s behaviors would have been diagnosed as “abnormal.” Our tolerance for difference has grown in the years since then. But our understanding of the clinical underpinnings of such differences remains limited and primitive.

To lay blame for Robin’s “condition” either on his mother’s death or on some genetic disorder is already to fall into that limited thinking. There are medical terms for Robin, to be sure. But they are almost all crude and pathologizing. As Theo puts it: “I never believed the diagnoses the doctors settled on my son. When a condition gets three different names over as many decades, when it requires two subcategories to account for completely contradictory symptoms, when it goes from nonexistent to the country’s most commonly diagnosed childhood disorder in the course of one generation, when two different physicians want to prescribe three different medications, there’s something wrong.”

We in the States still seem less interested in understanding “challenged” kids than in treating and altering them. Just a couple of days ago, Elon Musk announced on national television that he has Asperger’s Syndrome. That announcement may go a ways toward helping parents understand that neurodivergence is much subtler and more wondrous than they may fear, and not always in need of a “treatment.”

AV: There are several references to birds in Bewilderment. Theo’s late wife, Alyssa, used to go birding with her friend Marty Collier. Her son is named after her favorite bird. Robin shows his dad an owl that lives in a nearby tree. Theo and Robin see three sandhill cranes (which recalls your novel The Echo Maker) flying north, to which Robbie says, “How would we ever know aliens? We can’t even know birds.” Do you have an interest in ornithology?

RP: I have been an avid (if still totally amateur) birder since before I published The Echo Maker. I’m a total autodidact, but I’ve been to some of the greatest birding spots on the continent: The Platte River, Southwest Texas, Cape May. I no longer keep life lists or day counts, which tend to commodify the experience too much for me. I can’t always tell what I’m looking at (especially with warblers, in the spring and fall!). But the thrill never gets old, even in seeing “commoners.” I saw a pair of scarlet tanagers the other day (early in May, in the Smokies) that were so bright I thought for a moment that two bits of orange and red emergency reflective tape had blown up into the trees. When I hear the pileated woodpecker and the barred owl who live right near my house, it’s enough to make it a good day. A good bird sighting can match any artistic pleasure.

The Smokies are covered in suchdense forests that birding here is usually more of a matter of hearing than seeing. While writing Bewilderment, I began studying and learning the songs of the hundreds of birds who come through the area. A bit of musical background has helped in this. I’ve also become a devoted supporter of American Bird Conservancy, which does astonishingly good work, on a very limited budget, to preserve habitat and protect birds—highly recommended for anyone who’d like to perpetuate and extend the joy that birds bring!

AV: Theo creates imaginary planets with different characteristics for his Planet Seeker project. How did you come up with names like Mios, Nithar, and Zenia and the planets’ different features? How do these discussions help bind the father-son relationship?

RP: I took great pleasure in shaping and naming these planets in the hope that these voyages to surreal places would intensify the domestic realism of the rest of the novel. The names of the planets are playful trips in etymology, and I tried to cast a wide linguistic net in naming them. All the names grow out of ancient roots and have some bearing on the allegorical nature of each place. As all good religions understand, the mystery of our ability to know ourselves is also the mystery of language. Childhood consists of struggling to come to terms with a bewildering array of names and words. Every word is another planet.

The voyages that Theo and Robin take to these imaginary places are both a form of shared play as well as an exercise in mutual empathy. For the son, the stories are pure escape and emotional adventure. For the father, they are exercises in the recovery of childhood mystery and his own love for speculative fiction. I am lucky to be pen pals with Kim Stanley Robinson, a towering figure in contemporary American speculative fiction, and I sent him a copy of the book in galleys. He remarked on being taken back to his own early pleasures in the genre of 1950s and 1960s “planetary romances,” a tradition that he dates back to Melville and others’ travel romances to remote islands. He cites Le Guin, Pangborn, Vance, Sturgeon, and Brunner as being great practitioners of the form. These are writers whose influence I have felt with real force—writers touched with wanderlust and desire to travel beyond the constraints of an increasingly domesticated Earth.

Other planets are, of course, always other people, and dreams of travel are filled with the fear of otherness and the desire for unachievable empathy. But Robinson also hit on the jackpot point that all these travels to other planets are meditations on the unbelievable luck and incredible beauty of this one. As he put it to me, any alien father and son out there, dreaming up a place like Earth, would be tempted to laugh away the idea as way too rich and fecund and lucky to be anything but the wildest science fiction.

AV: The discussions Theo has with Robbie get into the Fermi Paradox. Robbie asks Theo how many galaxies there are in the universe and Theo says: “A British team just published a paper saying there might be two trillion.” This is mind-boggling. What are your thoughts about sentient life in the universe? Assuming there is sentient life and contact gets made in the future, doesn’t it make you wonder how we Earthlings would respond, especially since there is so much xenophobia in the world today?

RP: The math for calculating the likelihood of intelligent alien life is so full of gaps and unknowns that it truly is anybody’s guess. The denominator of habitable planets is growing rapidly, and it is already so large that it would seem to make the existence of intelligent aliens almost a certainty. But there are so many possible filters and bottlenecks that we can’t entirely calculate, since we are in the untenable position of reasoning from a single case—our own. Nevertheless, the smart money is leaning toward “Yes.” When I was young, it was almost taboo for serious scientists to talk about the possibility in public. Now, Astrobiology is a respected career. My lay-person’s hunch is that they are almost certainly out there, but at distances so great that we may never detect even indirect evidence and could never hope for direct communication.

As for how Earthlings would respond to any detection of life elsewhere: Now there is the classic SF question! And it has been answered in so many ways. Some writers point out that what Freud called “the narcissism of small differences” tends to gets tempered a bit when people are confronted with a much deeper outside difference. Some (I’m thinking of James Tiptree Jr.) seem to suggest that the desire for alien intimacy is the strongest urge we can feel. Others emphasize how resourceful and infinitely pliant a hatred of everything alien can be. Given human psychology, there may be a connection here!

I can’t pretend to understand humans, and I have no great insight into their profound, primal contradiction. We are xenophobic, yes, and our tribal loyalties can make us hate just about anyone and anything that does not look enough like us. But we are also filled, especially as children, with what E. O. Wilson calls biophilia. Children are born scientists. They also tend toward pantheism, and they can see God crawling all over every inch of the backyard. I want to write stories that can help return us to that state of consciousness, books that can reenchant and “bewilder” people in the etymological sense: to make them a part of wildness again. The chief crisis of humanity is that we see this planet not as a finite, living system but as a bottomless commodity to exploit and an endless terrain to subdue. We desperately need stories that can alter that. The most bewildering fiction is a kind of empathy machine, training us to see our seemingly disparate selves as imbricated in an unfolding, experimental network that is trying to travel everywhere.

AV: There are a number of scenes in Bewilderment that refer to the President, which the reader can assume is Trump, making outrageous decisions. One example is the President’s solution to stop forest fires in California by writing an executive order to cut down two hundred thousand acres of national forest. As a former physics student and an environmentalist who believes in science, what has it been like for you to have watched Trump with his anti-science approach to such things as global warming, conservation, and COVID-19?

RP: The President in Bewilderment isn’t Trump per se, but he is a very close fictional double! He, too, has figured out that in the era of digitally-leveraged politics he can sell fear, anger, hearsay, confusion, persecution, and paranoia much better and spread them much faster than humility, empathy, wonder, and science. The xenophobia, tribalism, and superstition whipped up during the four short years of the Trump administration have stunned and demoralized me. His outright rejection of empirical evidence in favor of wishful thinking destroyed not just the public’s belief in scientifically demonstrated fact, but also demolished anything that looked like a shared trust in any kind of accountable process for determining facts in the absence of consensual belief. The trend of those years was terrible and obvious: evidence has given way to wishful thinking, and ideology has replaced all appeal to empirical data and measurement.

The destruction of national set-aside land over the last four years, the removal of protections to air and water, the reversal of all our hard-won progress on climate change, and the redoubled war on everything that isn’t human tore the heart out of me. But the real tragedy of those years, one that will continue to harm humanity and all the rest of creation for a long time to come, was the massive resurgence of human exceptionalism that Trump fostered simply by preaching a sense of aggrieved entitlement. Trump’s white nationalism and his toxic male paternalism are part of a larger, unbridled gospel of human separation from and domination over everything else alive.

Good scientific practice, with its self-restrained and tentative nature, is helpless in the face of swaggering self-assertion and grandiose privilege. Rational argument, statistics, and an appeal to facts do nothing in such a battle. But stories can sometimes sway a reader’s heart, and the questions of children can sometimes shame adults into seeing themselves. That’s why the story of a child coming into the light seemed to me the perfect antidote to Trump’s America.

AV: There are numerous sentences throughout the novel that just sparkle. One example: “Rising from the leaf duff in a bowl-shaped opening off the path was the most elaborate mushroom I’d ever seen. It mounded up in a cream-colored hemisphere bigger than my two hands. A fluted ribbon of fungus rippled through itself to form a surface as convoluted as an Elizabethan ruff.” Is there a method to this creative architecture? Do you think of some exquisite sentence and write it down to be used later, or does your Muse inspire you when you actually sit down to write?

RP: Thanks for the kind words. I’m grateful to hear that. Of all the elements of writing, I have always been mostly drawn to explorations of style. When I was younger, that sometimes meant striving to create lots of sentence-level effects through diction, register, and elaborate syntax. I often tried to create a style that called attention to itself. As I grew older, I became interested in simplicity and constraint, while still searching for a language that was distinctive and unpredictable. Often this has involved a more passive approach to sentence-making than in the past. Nowadays I like to take the sentences I’m working on out on the trail with me. I don’t attack them with conscious attention, but rather, I let them percolate in the back of my mind as I walk, and I focus my attention on all the life around me in the woods. Before I’ve gone far—usually no more than a mile or two—the solution to the sentence or paragraph that I’ve been puzzling over will present itself to me, almost intact. Of course, the tiny bits of tinkering and adjustment continue when I get home, and those never stop, even after publication, I’m afraid.

AV: While discussing the Trappist planet, Robbie asks: “What about God, Dad?” Theo’s response to his son is, “I mean, God isn’t something you can prove or disprove. But from what I can see, we don’t need any bigger miracle than evolution.” Was there a point in your life that you came to a similar conclusion?

RP: I began falling away from traditional religion when I was a teen. The more I learned about the complexity of life and the shared features of biochemistry and genetics across all living things, the more spiritual power I found in the grand biogenetic synthesis. As Darwin suggested in the famous last lines of The Origin of Species, there is more miracle and greater potential for inspiration in the accreting discoveries of empirical science than there is in the Bronze Age story of a personal God, especially the anthropomorphized one we’ve inherited. If you’re talking about the creation of meaning, nothing is more staggering or meaningful than a sense of what a few self-replicating molecules have been able to manage, shaped by natural selection and the other regulators of evolution.

Religions based on a soul-testing God who is intent on the salvation of separate souls (a God who seems remarkably indifferent to the fate of non-humans, by the way) have proved to be a disaster for the planet. Yet religion is likely to be the only thing strong enough to compel people to rejoin and rehabilitate the living planet. We need a different kind of religion now if we mean to stick around here for much longer. I’m looking for that in all kinds of places, from Taoism to Native American belief in Interbeing. We need the pantheism of children and the sense of awe expressed by the best natural scientists. We need to remember that “religion” derives from deep linguistic roots that mean, literally, “tying back together.”

AV: “They share a lot, astronomy and childhood. Both are voyages across huge distances. Both search for facts beyond their grasp.” On one hand, Theo is a scientist who appears to be living in the real world while trying to deal with the reality of being a widower and single parent. On the other hand, he also lives in a simulated world with his imaginary planets. What are the consequences of this duality for the father-son relationship?

RP: My goal in creating Theo Byrne was to make him broadly sympathetic but also wholly ambiguous and questionable. That’s why the book is told in first person. First-person narrators are intrinsically unreliable, to some degree. They perform themselves for the reader, making the equivocal case for themselves even as they explore the limits to their own self-understanding. Theo seems aware of his ample faults, as a scientist, a friend, a husband, and a father, but readers are likely to have deeper insights into him that he himself has not yet been able to reach. That makes him something of a tragic character in the classic sense, I suppose.

And yet, for all his fallibility and the limits of his self-knowledge, I’d like to think that there is something redemptive to him. Philip Roth once said that we really begin to love a person when we see them trying to be game in the face of an impossible situation. As Theo became substantial for me, I couldn’t help but love him. He knows he is thrashing about, that he is ill-equipped for the challenges of his life, especially after the death of his wife, Alyssa. But there is nothing—nothing—that he wouldn’t do to try to protect and care for his son.

AV: To expand on the previous question, when Robbie begins experiments with Decoded Neurofeedback, he becomes so proficient that not only does his anger disappear, but he becomes incredibly intelligent. Do you think the roles of parent and child have been reversed to some extent? If so, to what betterment or detriment for each person?

RP: I suspect that everyone who has ever raised a child has, sooner or later, felt the roles of parent and child reversing. It’s a dirty little secret of myopia known to every child, as well! Mark Twain has a very funny line: “When I was young I thought what a fool my father was. When I became a man I was surprised how much he had caught up in the meantime.” The story of Robin’s accelerated education is an only-slightly-fabulistic exemplar of the uncanny (but not uncommon) moments when parents feel reminded, humbled, or outright schooled by the wisdom of their children.

AV: The Buddhist prayer Aly says to Robbie at bedtime—“May all sentient beings be free from needless suffering”—does not get answered. In fact, each family member experiences “needless suffering,” whether self-inflicted or not. Would you care to comment on the irony of this and the place of praying?

RP: It’s a matter of debate whether Buddhism is theistic. In general, though, prayers in that faith are directed not so much outward as inward, toward a self in need of transformation and interconnection. Aly’s prayer is derived from the Four Immeasurables, and to think on them is less a matter of petition than of practice. “Let me never cause needless suffering to another sentient being.”

The first of Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths is “the truth of suffering.” All creatures will suffer, and much of that suffering will be needless. But suffering can be lessened through a change in consciousness. The bedtime refrain that Aly taught Theo and that Theo teaches Robin is an expression of will that needless suffering should not be compounded. It’s a way of strengthening identification with all things and helping to see ourselves in everything that isn’t us. Just to say the words out loud is to start to change the consciousness of a culture that has not always admitted to how much needless suffering it inflicts. Prayer, like fiction at its best, is an empathy machine, a way towards that state of Interbeing where needless suffering diminishes.

AV: Making the analogy to Algernon, Robbie tells Theo that he is “still the same mouse, Dad. I just have help now.” Robbie also says he has “three really smart, funny, and strong guys” walking with him, “Just: like, they’re helping to row the boat or something. My crew.” What should the reader make of these imaginary friends?

RP: I think they should be just as bewildered by the words as Theo is! What’s happening to Robbie at this point is a locked room mystery. In fact, that’s true for the whole book. Theo never really knows what’s going on inside his son’s head. But when Robin starts training in Martin Currier’s empathy machine, Theo’s own capacity for empathy is really put to the test. How much of the improvement in Robin is being caused by the feedback? How much of the perceived benefit is only a matter of cueing? How much is Robin doing by himself, in the novelty of the experience and through the force of his own imagination?

Nabokov, in his great afterword to Lolita, talks about how he drew inspiration for the book from reading “a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature's cage.” We are each trapped inside our own heads, making art and saying sentences that bewilder other people. We will never know what it’s like to be another person, let alone an ape or a bat. No empathy will ever be strong enough to give us anything else but the View from Here.

But here’s the thing: when I read a book by someone from another time and place, maybe even someone who is long since dead, it’s like I have company, a helper in my head—my “crew.” I carry that feeling of having houseguests around with me, even after the act of silent communion and neurofeedback is over. The mystery is not what is in the other locked room. The great mystery is how the View from Here can sometimes become the view from anywhere.

AV: Robbie sees a young climate activist named Inga Alder on TV and, being inspired, decides to do his own protests at the state’s and nation’s capitols. Greta Thunberg, her seeming real-world counterpart, also has Asperger’s, which she claims is a gift. What do you think about Thunberg, who dropped out of school to bring the world’s attention to climate change, and her connection to Robbie?

RP: I’m never comfortable giving away my keys to open any roman à clef, but this one kind of gives away itself! Inga, like Thunberg, declares that her cognitive “challenge” is really her superpower. Robin himself immediately recognizes the affinity, the moment he first sees her and hears her talk on television. He says, “She’s like me, Dad,” and the words make Theo’s skin pucker.

Thunberg is an astonishing and unique spokesperson for a new human consciousness. The need for humans to come back and live here, inside the webs of the living planet, has rarely been more powerfully articulated or advanced. There is no gainsaying her blunt willingness to confront the truth and to challenge our attempts at denial and self-deception. I believe that Thunberg’s skills, her courage, her moral clarity, her powers of persuasion, and the truth of her vision are in no small part a function of her “superpower.” It may well be the neurodivergent who lead the way in the transformation of human culture that we will need in order to preserve and extend this planet’s experiment in self-awareness.

AV: There is a scene where Theo and Robbie are in the backyard at night which Theo recounts: “He propped his head on the pillow of my arm. For a long time, we just looked up at the stars—all the ones we could see and half the ones we couldn’t.” Then Robbie says: “Dad. I feel like I’m waking up. Like I’m inside everything. Look where we are! That tree. This grass!” This scene, which echoes the book cover, shows the love of father and son as they share this wonderful, magical moment in time. Was this scene from your own childhood or something else entirely?

RP: I remember many such moments of “oceanic consciousness” from my own childhood, and I have continued to experience them, although less frequently and intensely, as an adult. But this scene came about from my trying to inhabit Robin’s consciousness as fully as I could. To show him at his zenith, as his ability to experience “Interbeing” reaches its peak, I read a great deal of spiritual and religious writing, especially in the Eastern tradition. The writer Charles Eisenstein was helpful throughout. I also turned to the best examples of “nature visionary” writing, both classic, like John Muir and Aldo Leopold, and contemporary, like Robert MacFarlane and Robin Wall Kimmerer.

AV: In many of your novels you explore various types of consciousness and how individuals think and express themselves. What are your thoughts about humans having implants in the future?

RP: To some extent, Bewilderment is itself wrestling with the question of technologically-mediated consciousness. It does so through the fable of neurofeedback, of course, but, more fundamentally, it dramatizes Theo’s dilemma of whether to medicate his child. Therapeutic drugs have helped countless people function better on this planet, but Theo is reluctant to experiment with them on such a young and still-forming brain. For him, the ways of going wrong in such an experiment outnumber the ways of going right. But more importantly, he isn’t convinced that his struggling child needs to be cured of anything. How much should he try to “correct” his child, simply to conform to contemporary practice in raising children?

These questions of clinical treatment shade off into the increasingly real question of cognitive or emotional enhancement. (Think of the number of students out there taking ADD medication, not to treat a diagnosed condition, but to improve their academic performance.) I have no doubt that humans will get better and better at controlling and mediating mood, emotion, behavior, perception, and cognition through pharmacology and other kinds of neural intervention. But I also know so many kinds of neural interventions—music, love, hiking, poetry, sitting by the river, breathing in a cascade’s negative ions—that I’d rather experiment with.

AV: It seems evident in the recent stages of your writing career that you are very concerned about our environment and the impact humans are having on it. Since moving to the Smoky Mountains, some readers might consider you as a modern-day Thoreau. What are your thoughts about the future of our environment and are there any organizations that concerned citizens should consider supporting?

RP: There are so many! Those that concentrate on the reversal of habitat destruction are especially important to me, as that will be the key to slowing down the mass extinction that we are inflicting on the planet. The organizations Save the Redwoods, Old Growth Forest Network, the National Forest Foundation, and American Forests do good work in this country. I’ve already mentioned American Bird Conservancy, which is one of the most effective and efficient environmental organizations around. Wangari Maathai’s Green Belt Movement is helping to transform Africa. Look for smaller, targeted, lean and efficient organizations that are doing work close to your own heart.

Perhaps even more useful than sending cash to such outfits is committing yourself to hands-on efforts where you live. Rehabilitation begins at home, and to the extent that we are going to reintegrate in a sane way with the living planet, it will be through local efforts to understand and restore what life wants to do nearby. Why not start in your yard? Get rid of invasives, plant native species, give up your desire to control things with chemical inputs, and love what happens when local life comes rushing back in.

AV: Your books never seem to repeat themselves. This allows your readers to examine and reflect on life in ways they ordinarily would not. To paraphrase one of your sentences from Bewilderment, your novels let the reader “wormhole” into a different world, even if all of your novels are not “small, light, portable parallel universes.” If this question is not too impertinent, can you provide an example or two where you might have read a book and decided “I want to write this type of novel”?

RP: That’s not at all impertinent to ask. I do this all the time! In fact, I have spent much of my life like Borges’s “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote.” (I really, really wish I could have written that story.) At one time or another, I have wished that I could re-write, verbatim, works by Melville and Byatt and Proust and Pynchon and Stoppard and Mann and LeGuin and Mitchell and Whitehead. The list is long, and a certain kind of emulation-gone-astray has left genetic markers all over my thirteen novels. For Bewilderment, in addition to Flowers For Algernon, I took lots of inspiration from Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams, Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker, and so many others.

AV: On its surface, Bewilderment could be viewed as a straightforward novel about a father and son relationship, a mystery novel, or even touching upon the realms of science fiction. It also seems to have affinity with fabulist writers such as Calvino, Borges, and Barth. Do you welcome such comparisons and would you ever consider writing a science fiction novel?

RP: I have lived my whole literary life, both as a reader and a writer, straddling that gap between psychological realism, on the one hand, and formalist, fabulist, or more “experimental” writing on the other. Ordinarily, people seem to show devotion to one side of this dualism, and abhorrence for the other side. I love them both, and I’ve struggled for a third of a century to find ways of writing books that can triangulate between and combine what Zadie Smith famously called these “two paths for the novel.” So it thrills me that you feel that “a straightforward novel about a father and son relationship” might also owe a debt to Borges, Calvino, and Barth! All three of those writers have had massive influence on me, and I had them all in mind at one time or another as I wrote Bewilderment. I wanted to hybridize modes and aesthetics in a way that showed how porous that species boundary really is.

But in this book, I had other motives for trying to fuse realism with fable, reasons having to do with the subject matter of Bewilderment. The novel, as a form, is one of the most complex and effective empathy machines that humans have yet come up with. It works best when it can excite all kinds of concurrent but sometimes incommensurable parts of the brain. The strange loop of fiction makes it possible for us readers to reflect on our own processes, even while we are immersed in the stream of them. And while reading, we begin to see how much of what we take to be inarguably real is, in fact, the result of fabulous maps and shorthand fables that we ourselves have created. Likewise, the primal fables that the best fiction serves up can come away reflecting the most practical and hard-headed realism.

You ask if I’ve ever considered writing science fiction. As I see it, Bewilderment is itself science fiction, in the purest sense. The entire book takes place on a counterfactual Earth, it invokes a dozen voyages to other planets, and it hinges on a plot involving a level of neural technology that doesn’t yet exist. But the fact that it didn’t feel like science fiction to you pleases me. Not that I’m unhappy with the label of science fiction writer. Galatea 2.2 and Plowing the Dark both used science fiction, and Generosity was a finalist for the Arthur C. Clarke Award for science fiction. I’m always proud when SF writers like Kim Stanley Robinson and Carter Scholz claim my books as SF. My aim, though, is to absorb the science fiction elements into a texture of plausible realism and to tell a story where facts and fable fuse seamlessly in the reader’s mind.

AV: When I saw you speak at Rice University for a reading of The Overstory, you were gracious enough to let your good friend Tayari Jones speak after you. I thoroughly enjoyed her novel An American Marriage. Are there any other novels by writers that you might suggest?

AV: When I saw you speak at Rice University for a reading of The Overstory, you were gracious enough to let your good friend Tayari Jones speak after you. I thoroughly enjoyed her novel An American Marriage. Are there any other novels by writers that you might suggest?

RP: Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena was one of the most ambitious and achieved debut novels I’ve ever read. I really enjoyed The Alaskan Laundry, by Brendan Jones, who I worked with when I was at Stanford. I was lucky to read Sandro Veronesi’s novel The Hummingbird, which made such a splash in Europe, in an early English galley. It is just now being published here. David Benioff’s City of Thieves was very well done. Anything by the extraordinary writer Colum McCann will provide great rewards.

AV: I cannot put into words how much your writing has brought enjoyment into my life. Since you quoted a Buddhist saying in Bewilderment, I will leave you with another Buddhist saying: “What we think, we become.” Thank you for your sublime novels and for doing this interview.

RP: Thank you for such kind words. Regarding your Buddhist saying, I used a similar quote, by Bernard of Clairvaux, as the refrain in my novel Galatea 2.2: “What we love, we shall come to resemble.” When an idea pops up in two such different cultures and traditions, perhaps there is something to it! I’d also like to hope that what we read and think about, we will come to love.

Click here to purchase this book

at your local independent bookstore

Charles L. Hughes

Charles L. Hughes

Saturday, October 16, 2020 • 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

Saturday, October 16, 2020 • 10:00 am to 5:00 pm

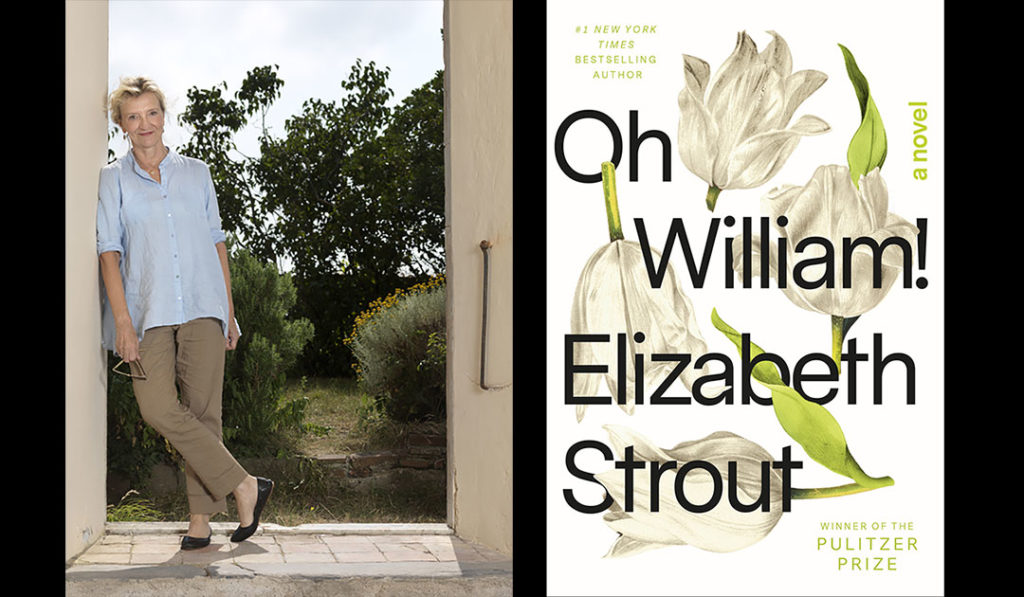

Elizabeth Strout is the Pulitzer-prize-winning author of Olive Kitteridge, which was adapted into an Emmy-award-winning mini-series. Her other books include Amy and Isabelle, Abide with Me, The Burgess Boys, My Name is Lucy Barton, and a sequel to Olive Kitteridge, the 2017 Anything is Possible. She divides her time between New York City and Brunswick, Maine.

Elizabeth Strout is the Pulitzer-prize-winning author of Olive Kitteridge, which was adapted into an Emmy-award-winning mini-series. Her other books include Amy and Isabelle, Abide with Me, The Burgess Boys, My Name is Lucy Barton, and a sequel to Olive Kitteridge, the 2017 Anything is Possible. She divides her time between New York City and Brunswick, Maine. Julie Schumacher is a professor of creative writing at the University of Minnesota and the author of multiple novels and collections of short stories, including The Shakespeare Requirement and Dear Committee Members, which was awarded the Thurber Prize for American Humor.

Julie Schumacher is a professor of creative writing at the University of Minnesota and the author of multiple novels and collections of short stories, including The Shakespeare Requirement and Dear Committee Members, which was awarded the Thurber Prize for American Humor.