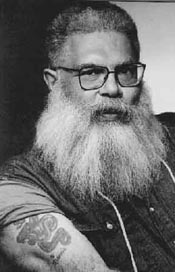

by Rudi Dornemann and Eric Lorberer

SAMUEL R. DELANY'S many books offer not only the beauty of well-turned phrases and the spark of provocative ideas, but an illumination won from the exacting exploration of self and society. In science fiction, literary criticism, comic books, memoir, or pornography, to read Delany is to discover. Showing us what we as readers didn't already know, he freshens our eyes for what we had always accepted as familiar.

Delany's writing career began in the precincts of science fiction in the early '60s—earning him the highest awards in the genre before he was 30—and has continued through further SF landmarks (e.g., Dhalgren and Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand), the four volumes of philosophical fantasy in his Return to Nevérÿon series, transgressive novels (Hogg and The Mad Man), works of memoir and family history (The Motion of Light in Water and Atlantis: Three Tales), and numerous collections of essays and criticism. This year, he has added two books to his nonfiction column: Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts & the Politics of the Paraliterary (Wesleyan University Press, $22) and 1984 (Voyant Publishing, $17.95).

While the former of these new books speaks for itself, the latter may demand some explanation. In ironic homage to one of the classics of "literary" science-fiction, 1984 shows us the year of Orwell's nightmare prophecy from the vantage of the present, offering a well-chosen selection of Delany's letters written during that year. There are intriguing parallels to Orwell's vision; "Big Brother" here appears in the guise of the IRS, who lay their claim on every last cent Delany earns, while "sexcrime" is explored through Delany's musings on the changing pornographic underworld during the advent of AIDS and gentrification (a subject given his full critical scrutiny in last year's Times Square Red, Times Square Blue). With all the grace of an epistolary novel, 1984 is a riveting look at a year in the life of a struggling writer.

As is Delany's practice, the following is a "silent interview" in which the author responded to our questions in writing. A shorter version of this interview appears in Volume 5, Number 4 of Rain Taxi Review of Books.

RAIN TAXI: References to poetry are sprinkled liberally throughout your writing—1984, to cite only the latest example, begins with a double-barreled meditation on the onset of AIDS and the death of poet Ted Berrigan. Clearly poetry is important to you, despite the fact that it's one of the few genres you haven't written. Can you talk about the role of poetry for non-poets?

SAMUEL R. DELANY: Because I like to read poetry—and like to read about poetry—I'm tempted to start with the most pragmatic answer: As a prose writer, I work with language; and those who work with language turn to poetry for renewal. But that's a metaphor—and sometimes it's difficult to turn up the focus on the experience itself to analyze just what the reading of poetry gives.

Among my recent enthusiasms is the critical work of the late poet Gerald Burns. In a slim pamphlet called Toward a Phenomenology of Written Art, in "The Slate Notebook," the first of the two essays that comprise his book, Burns writes:

Some writers know a great deal about how words should come at a reader; others study the ways words come to a writer. The second is likely to please passionate readers more, if only because the first is more likely to be vulnerable to literature as rule book, a catalogue of other men's effects. What saves him sometimes is reading very little. The second, whether reading or writing, is likely to pay less attention to the book of rules than to grass and how the ball looks coming at you, and the oddity of lines painted on a field. What he explores is the act of writing, as his readers explore the act of reading. There is nothing contemptible about traditionalist writing, but its readers are more likely to ignore the act of reading as part of the experience of what is read. In the first-quarto Hamlet Corambis asks, What doe you reade my Lord? and Hamlet says, Wordes, wordes. In the Folio he says, Words, words, words. It's not only funnier, it's truer, to his and our experience. The scribe may hate his pen as the painter his paint, but in another mood he will imitate Van Gogh and drink ink.

Around his baseball exemplary (borrowed, surely, from Jack Spicer), this kind of insight locates our attraction to poets from Pound of the Cantos, through Laura (Riding) Jackson, Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, and Jorie Graham—and is one you're only likely to hear from a poet. The writers of prose fiction whom I can easily think of who fall in with those writers more interested in how words come to the writer than to the reader are D. H. Lawrence and the greatly underrated Paul Goodman. Today, language-aware prose is, indeed, more likely to be concerned with the reader. William Gass or Guy Davenport, Richard Powers or Edmund White are all writers primarily interested in the reader. As, I confess (my Nevèrÿon tales excepted), am I.

Still, from time to time it's interesting—as Burns suggests, obsessively so—to read writers who are interested first in how language comes to them.

In his long poem "The Alphabet" (the Prelude of our times), in the S-section, "Skies" (in the book ®, which includes three sections, "Quindecagon," "®," and "Skies," Drogue Press: New York: 1999) Ron Silliman gives us the detritus of many days' looking at the sky—of going out and writing at least a sentence a day about it. The result? A sensuous, sumptuous, and remarkably analytical cascade of perceptions, focused on one great natural field. Another thing we turn to today's task-orientated poetry for is the performance of those language undertakings that we prose writers are just too lazy, or, yes, too insensitive, to try.

Hart Crane—to cite a poet I love and have written about, both in critical essays and as a character in fiction (Atlantis: Three Tales, Wesleyan, Middletown: 1996)—is a poet who lets me into a hyperarticulate universe, where I'm privileged to hear the entire inanimate world given voice. Considering gay history, it's fascinating that, in an incomplete poem ("A Traveler Born") written in 1930 about his various sailor conquests, a gay poet should mention the "Institute Pasteur" where the AIDS virus would eventually be isolated fifty-three years later. In Crane's poems, ships, waves, cables, rain, sea-kelp, and derricks all sigh, scream, choir, and return words, song, letters, and laughter for speech. Eliot meditated on the significance of what the thunder said through the medium of the second Brahmana of the fifth lesson of the Bhradâranyaka Upanishad. In his poem "Eternity," Crane crawled out from under the bed the next morning, sat down, and, amidst the wreckage, pretty much transcribed what he saw of its effects directly.

In some situations—though I'd be hard-pressed to give them a coherent characterization—this is not just invigorating. It's downright useful.

Gertrude Stein knew she was a genius, and she wanted to show that the way language comes to geniuses is insistently simple; it arrives in the mind of those who can really think with a clarity, a lucidity, and a strident and self-reaffirming simplicity that is all but one with the language of the child. When someone like Blanche McCrary Boyd advises writers today, "Write as simply as you can for the most intelligent person in the room," she is encapsulating—she's aphorizing—the dramatized wisdom of Stein's Lectures in America and How to Write.

I don't think I can leave your question without noting that those writers concerned with (that is to say, who fetishize) how language comes to them rather than how it goes out from them tend to be on the conservative side.

They're the writers who don't question why the words for the gallery of writing techniques come to them as "men's efforts."

Because that's the way it comes, that's reason enough for someone like Burns to preserve it.

In 1966 and '67, after I finished a novel called Babel-17, in the various articles I was writing here and there I began to use "she" and "her" as the general exemplary pronoun. In the 'sixties and 'seventies, copy editors regularly used to correct me, changing my "the writer she" back to "the writer he"—and, if I could, I'd put it back, though I didn't always get a chance. I'd never seen anyone do it before. The decision was purely intellectual. But after having written a whole novel about the trials and tribulations of a woman poet, I just couldn't go on accepting the notion that everything from children to animals to writers to parents were composed of nothing but males. I know a few writers—specifically in the science fiction field—took the idea over from me and began to do it too.

Today, thirty-odd years later, it's pretty common. I'm quite prepared to believe other people—women and men—got the idea independently of me, or of any of the people who (like Joanna Russ) borrowed it from me. Possibly someone did it even before me. But this brings up the whole notion of voluntarism in language—a tricky and difficult topic. Conscientiously changing the language is only likely to be done by a writer who fetishizes how the words strike the reader. But the experience of the modern "man" from the 15th Century on has been that of the language which society gives her or him not describing the world she or he knows to be the case. Whether it's the suggestion (that comes directly from the classical languages) that the child (that is, the important child in the family, the one who will be a citizen, the one who will inherit) as soon as it stops being an "it," becomes a "he," or that the sun rises and sets (instead of stays in one place while the earth turns below it), or that, by seeing and hearing things, the subject does something to them, rather than being neurologically excited by them in some way, or that electricity runs from positive to negative (shortly after the poles were assigned, of course, it was discovered that the electrons actually move the other way), language constantly remains inadequate to describe accurately what we know of the world—unless we're willing to take it by its neck and, well . . . after wringing it and slapping it around a little, voluntarily changing it.

Most of the time, we negotiate this inadequacy by developing twin rhetorical traditions. We still say that the sun rises in the east—even as we talk, in terms of time differences, of the earth turning "beneath" (itself a ridiculous concept, since, during its night, Australia is in the same orientation toward the solar center as is daytime Canada: only the earth's globe lies between) the sun. The logical way to speak of it, however, would be to say that the whole earth moves in an orbit 93-million miles above the sun, as the moon orbits above the earth—and, indeed, as the sun revolves thirty thousand light years above and about the massive black hole probably at our galaxy's center. "Above," in this situation, is new diction. It hasn't been used before. The anti-volunteerists say that you can't change language voluntarily. I say, if it makes sense to you, use it; now; from now on—and we will have changed the language, just as those of us who started using "she" as an exemplary pronoun comparable with "he" changed it in the late sixties and seventies.

RT: 1984 is titled after one of the best known works of literature (or some would say science fiction). What is it you want to remind us of Orwell's relevance as his apocalyptic date recedes into the past?

SRD: I was going for irony: A science fiction writer writing a nonfiction book about a time in the actual past that was, for so long (and still is, by so many) considered to be science fiction. In that sense, the title was used in a poetic (if comic) way, rather than as a hard-edged reference to some synopsizable Orwellian politics. Some of those poetic relationships between what Orwell was doing and what I was up to are beautifully and intelligently unpacked and teased apart by Kenneth James in his "Introduction" to the letters that largely make up the book.

RT: You've constructed fictions which implicitly and/or explicitly reference large intellectual frameworks such as semiotics or deconstruction. Do you see any relation between ways in which your work is informed by literary/critical thinking and ways in which the works of other SF writers have been informed by other bodies of thought—for example, theories of history and Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, or eco-political ideas and Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars and California trilogies?

SRD: You've hit the nail on its head with your question. In stories trying to put over some notion from cultural or theoretical studies, really the writers aren't doing anything very different from what Asimov was trying for in his Foundation tales. The first handful of stories in Foundation—the first volume—attempt to get across some of the fundamentals of historical materialism. You know: A society that has a scarcity of metals is likely to develop differently from one in which metals are in excess. A society that is all water and wood is likely to develop differently from one with a plethora of ceramics.

People are pretty comfortable with the notion of SF as the literature of ideas. Well, personally I've been trying to pull that firmly tucked-in blanket up over the shoulder of Sword & Sorcery awhile now. In the midst of my more grandiose day dreamings, I've suggested that the Nevèrÿon stories are in the same line as Isak Dinesen's "gothic" tales. But the mumbled truth is that they're even closer to all those lunatic volumes Frank Herbert kept turning out before he wrote his Dune books, that nobody ever looks at any more.

SF writers have always liked to play with ideas of history.

The idea that ecology is a major historical force—as it is in Robinson's vision of the terraforming of Mars—resonates clearly with some of the work of Braudel and the Annelles historians and other historians of the long durée.

RT: In other interviews, you've talked about the process of using memories in which you perceive a certain "beauty and formal order" as a starting point for writing—even when your subject matter is outside what is usually treated artistically. And you've written about the idea that "human beings have an aesthetic register," which "manifests itself as a desire to recognize patterns." Have your ideas/perception of what constitutes "beauty and formal order" changed over time? Do you discover different aesthetic patterns in your experience of the world now than you did when you were first writing?

SRD: They've changed surprisingly little. I still believe pattern fascinates on its own. And three-sevenths of a pattern, or even a smaller fragment, can fascinate still more—get us really hunkering down, trying to tease out the whole of the figure in the carpet. Pattern is repetition of symmetry. And, as Freud told us in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, "Repetition is desire." Classical antiquarians used to call it ex pede Herculem—from only the statue's marble foot, they would try to reconstruct the entire form of the luminous, lowering demi-god.

Certainly there's new content to write about.

As certainly we are all drawn to some content—emotional, political, sexual—more than others.

But over time we can all watch what once seemed inescapably pressing because of the strident relevance of its content loose more and more of its interest till it's nothing but a formal arrangement.

From The Red and the Black (1830) through Huckleberry Finn (1884—85) and The Way of All Flesh (1904), a whole stream comprising some of the most revered work in Western fiction turn on the oedipal notion that the older generation feels it's due respect and deference from the younger because it's lived more, seen more, and done more—while the young rebel, claiming they must be allowed to discover the machinery of the world for themselves if for no other reason than the workings of that machinery is always in flux. There have always been many people for whom you only had to state the idea to raise in them a frisson of recognition, a thrill of identification.

Well, a few years ago, I had a surprising revelation. A significant proportion of my undergraduate literature students simply didn't relate in any major way to that "universal" notion, through no more complex a situation than having grown up with moderately reasonable parents, who simply weren't concerned with those orders and strictures of formal deference. That whole concept of intergenerational respect leans with ponderous weight on the notion of huge amounts of land, labor, and wealth passed from generation to generation.

Well, save some pots and pans, a ring, and some linen, I received no direct inheritance from either of my parents. Once an aunt of mine left me a legacy amounting to slightly under three months rent. Alas, whatever I leave my daughter is likely to be equally minimal.

The 19th-century concept of independent incomes passed from parents to children—incomes without which civilized life would be inconceivable—is simply not a part of the current standard order of all civilized life for most of us—though it was the topic of the 18th and the 19th-century novel. With all that economic responsibility unto eternity lifted from the shoulders of parents and children, life has probably been—locally—happier for lots of us. That means there's a growing generation for which any image of the good and forgiving father doesn't immediately bring tears to the eyes with the deep and tragic realization that, in their childhoods, they have never had one. (He was too busy building up something to leave you to be bothered to love you. Oedipus himself was, after all, a displaced prince, who won back his kingdom through murder most foul.) The tyrannical father doesn't immediately enlist them in a pact of identificatory anger that can now be turned against all unfair authority. These students' appreciation for the works that appealed to these patterns was primarily intellectual, and their esthetic response was limited to what greater and more intricate patterns the writers had embedded this oedipal material within.

Despite the creeping (and rather Spenglarian) Manicheanism of Slavoj Zizek, I don't think this is necessarily a bad thing—even as it moves some of the works I think of as personally and wonderfully powerful over or out a notch in the generally stabilizing canon structure.

RT: Are there artistic movements or particular artists you find particularly interesting, new ways of seeing the world in fiction or science fiction, comics or poetry, drama or visual arts? Conversely, do you feel there are parts of social reality for which there isn't currently an adequate artistic language in which to convey/reflect/express/discuss them?

SRD: I have been teaching for the last few years. The tragedy of that situation is the restrictions it imposes of how much of the world—especially the world of art—I get to explore. The Poetics Program at the State University of Buffalo where I teach has brought me in contact with an exciting stream of poets. But to say that Nick Piombino has some extraordinary ideas about poetry, which, in conjunction with his work as a psychoanalyst, have produced some fascinating essays and poems; or to say that Nicole Brossard has penned some scrupulously elegant fictions that attack the edges of poetry and appropriate them for themselves; or to say that Christian Bök's constructivist energy and historical intelligence is jaw dropping—well, I'm not sure what that says about anything other than my own enforced provincialism over the last few years.

What we now have to realize more and more, as high art becomes more and more democratically accessible, however, is that we only become more and more provincial.

I've been delighted and entranced with all of Alan Moore's ABC comics—Top Ten, Promethea, Tom Strong, and the wonderful camp extravaganza, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, with its intrepid leader Mina Harkner (née Murray), escaped from (but not unscarred by) Dracula's clutches. And I was wonderfully glad to see the single-volume edition of the Moore/Campbell From Hell. (Are you as curious about the movie, due for next summer's release, as I am?) Hellblazer seems to have gotten a new shot of ingenuity from wherever. (Did you ever read Maggie [The Book of the Penis] Paley's wonderful novel from 1986, Bad Manners? It wrings more esthetic use out of the telephone than any work since Cocteau's Le Voix humain. And I was intrigued by, if I didn't exactly enjoy, Coetzee's Disgrace.) White Out and White Out Melt were—as the kids used to say—awesome. The Sin City volumes and 300 were extraordinary offerings from Frank Miller. And since The Preacher recently concluded, yes, I've missed it.

The point, of course, is that there is a great deal of artistic energy in flux and a-swarm out and around in the making world. Turning to authorities to validate this or that section of it may be a necessary evil. What makes it an evil is, however (and keeps it from becoming a contribution to the aesthetic landscape's general health), the lack of an adequate language in which the general public for art can express its own enthusiasms, it's own interpretations, its agile and motile movements of attention.

But then, I suspect most of life takes place in the interstices of what's already been articulated. We call it discourse. Finally I think a question like yours has always got to be posed as part of a two-way process. After I give my answer, I am obliged to ask immediately, as if, indeed, the asking were only an extension of my response: And what new works and artists are currently exciting you?

Without that reciprocity (again I want to put the ball back in the reader's court), the question—and any given answer from any given person—must be, as some of us have lately been known to murmur, radically incomplete.

RT: In the last book of your Return to Nevèrÿon series (Return to Nevèrÿon [1987]), you claim you "write yearning for a world in which all these stories might be merely ‘beautiful,'" and go on to write that such a world might be possible in ten or twenty years, and that "That world would be, in many ways, the world I conceived of as Utopia." Is that world any closer now?

SRD: Paradoxically, I'm the last person to answer that. Whatever determines my worldview, really determines it. I have to remain blind to it. For me, no, those stories can never be "merely" beautiful.

That's something for our children to decide—or our children's children. We fashion meticulously and with as much strength as we can a wrung for the ladder we only hope, once those children, grown now, climb it, they can finally throw away. Politics is the most quixotic element of art . . . Still, I think those critics who believe it doesn't belong there at all are deluded. Was there ever a more political writer than Shakespeare? Those histories were all colored by, as they commented on, contemporary politics. The wheat riots in Coriolanus were inspired by similar riots in English during the previous year. And Polonius was a knowing satire on Elizabeth's prime minister, Lord Burley. Yes, politics is what time erases from art; and the art must be well-enough constructed to stand without it, once it has been removed by historical ignorance. Still, without the political goad, often we would never have had the art in the first place. Honestly, Sentimental Education is a better novel than Madame Bovary, precisely because of its richer political concerns—the source of its richer esthetic elaboration.

When you stroll down the street at 4:19 in the morning, and you suddenly stop—to look at two crows playing in a pine tree across whatever suburban street fate has stuck you on for the last year-and-a-half, there's a history of crows, a tradition of crows, a discourse of crows that's stopped you, and because you've stopped and are looking at them now, you can never be wholly aware of what that discourse, that history, that tradition was.

Sure, a moment on you recall the pair in the Neibelunglied, but you don't recall the one you saw savaging a red cardinal carcass on the highway's edge when you were five, or the one with the bilious tongue your father's friend—Connie, I think his name was—split with a razor to make it talk, because he was under the mistaken impression that such cruelty would re-articulate the species and make of it a dusky parrot. Fiberglass curtains blew around the cage in the Harlem back window, while—its swollen tongue pink as a rose hip, holding apart its grey-black beak--the bird eyed me blackly, then looked down at the newspaper over the cage bottom, scattered with seeds and shit . . .

The really repressed, the inchoate, the inconue that one masks with public dragons and genre determined strong men and women, to whom one loans one's most cherished ideologies, one's most committed desires, to make them strong enough to possess and hot enough to be possessable, they just don't yield themselves up so easily as a pair of birds at play above the November sidewalk. That's why we turn to them through genre tropes—because we don't know what they're really about. That's what we need public symbols for—symbols that alone let us negotiate the unknown and the unknowable.

It's because we can't grasp, really, what they are to us, that, moments later, as the crows fly off above the green and orange alley, our throats suddenly fill and we are trying not to cry—

So then, angrily, we write about dragons.

RT: As you have added more autobiographical works to your oeuvre, you've also brought to the forefront matters of race and sexual preference, yet often in the most unpolitically correct ways—your books are unlikely to be accused of being "identity art." What does the culture at large need to do to more adequately discuss these most basic of subject-positions?

SRD: Fantasize—and fantasize in modes that allow our most cherished and forbidden inner worlds to peak out (and speak out) here and there. Fantasize. Analyze. The two are related by much more than the slant-rhyme. In order to negotiate the unknown with any precision and intelligence, analysis has to become speculative. That's where fantasy's roll grows inescapable.

It's scary to talk about your own fantasies—to plumb that part of one's inner autobiography: the part we return to to initiate masturbation, the part that centers our reveries of anger or tenderness. Bring analysis—rather than blanket acceptance or rank dismissal—to those thoughts, and you'll find out how the world, dark or light, might figure itself under passion's stress.

RT: You have been adamant about the need to consider paraliterary genres on their own terms; indeed, the desire to make science fiction (or comics, or pornography) "literary" (i.e. more respectable) is probably reactionary at best. Yet isn't a genuine hybridization of genres possible? Your own work can easily be described in such ways: Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, for example, combines candid memoir with sociological analysis to produce a new kind of urban study. To take another example, your novel The Mad Man is a pornographic work—no question—yet it is also a serious erudite work, and serious erudite pornography is, we imagine, so rare that it might constitute a different genre, or at least warrant a different term.

SRD: To take the first half of your question first—about taking the paraliterary genres on their own terms: It depends on what terms you identify as "their own." If you mean only the terms that "literature" has set aside for them—and that now and then one finds the paraliterary genres have appropriated for themselves in an attempt to survive—then I think the idea is absurd.

An example: Paraliterature is just entertainment and is without further value.

Another: Paraliterature has no necessary history that helps us understand and appreciate it.

These are ideas about paraliterature you can find within the precincts of paraliterature today just as easily as you can find them—at their source—within the literary precincts, where they originated.

But the talk of origins is always distractionary and ideological. The point is, genres are never pure. Genres were never pure. The splits between them, while always noticeable, always oppressively there, are most important, most valuable by virtue of what they allow to cross over (what has always-already crossed over)—and the speed or slowness with which they allow those crossings. When one is talking of a relatively slow speed (such as the time it takes for intelligent attention to pass across the boundaries set up in the 1880s and 1890s, when the provisionary notion of dismissing entire working-class genres out of hand laid the ground-work for the subsequent academic creation, momently after the Great War, of the genre collection we call, today, literature), it's easier to speak of impedances. That is to say, is the glass of water half full or is it half empty?

Above I spoke of the socioeconomic conditions that, until recently, informed at least one of the structures associated with patriarchy—the patrimony—with its pathos and glory: itself the pathos and glory of the family-anchored hero. Well, the pathos and glory of the non-family-anchored hero is precisely the socio-economic situation that is growing more and more to replace it. The non-family-anchored hero in literature begins to come into its own with the hero of Knut Hamsun's Hunger; and, with Hamsun's disciple Henry Miller, spills out into the various tropics, onto the lush landscapes of Maroussi and the Sur. It also presses so close against the walls of pornography that we can't take it further without rupturing those walls and looking closely at what we find on the other side.

Both science fiction and sword and sorcery also tend to feature non-family anchored heroes. (Personally, what I'm interested in is what type of object the family becomes when, within such a genre, you do turn and examine it with the appropriate modicum of fantasy and analysis.) As I've written elsewhere, the hero of the S&S tale is not the prince with his endless entanglements with various potential fathers-in-law in terms of the princesses to be rescued. Rather, he is the unencumbered troll—Chyna, Hacksaw Jim Dugan, Luna, the Rock, Jacquelyn, Mankind, Booker-T, Conan, Saturn, Sable, Eddie Guerrero, Jr., or Goldberg—grown in human proportions.

RT: A term that's been used increasingly in the last decade or so is "slipstream." The term (like any) is used in various ways, now meaning literary fiction which adopts paraliterary techniques and tropes (as in some of the work of William S. Burroughs or Marge Piercy), now referring to describing science fiction / fantasy which employs the tropes and techniques of literary fiction. As well, it's marked perhaps with a certain surrealism (for instance, some of the fiction of Jonathan Lethem or Stepan Chapman). You've maintained that what sets science fiction (or any paraliterature) apart from literary fiction is that it needs to be read according to a difference set of conventions. How should one approach this "slipstream" fiction which seems to occupy a twilight region between the two genres? Are the reading conventions of either science fiction or literary fiction appropriate here, should readers mix conventions from both sides of the literary/paraliterary divide, or is "slipstream" developing its own way to be read?

SRD: You're imputing ideas to me which, while your expression uses a couple of terms that I've occasionally used, are just not mine. There are many, many ways in which a given text recognizable as belonging to a given paraliterary genre is likely to be different from a given text recognizable as belonging to a given literary genre. (You're not likely to mistake the ironic banalities in John Ashbery's Three Poems for the equally amusing ironic banalities in Alan Moore's Tom Strong. They come from two different traditions. Put bluntly, one's a comic book; one's a poem.) But there are many ways in which they can be the same. If the paraliterary text happens to be well-written enough, and also the vessel of what Nabokov once referred to as "sensuous thought" (his particular description of art), then you might find yourself advantaged by bringing across the divide the kind of intense attention more typically devoted to literary texts. Now—and only now—can we get to the point I think you are trying to make, above.

Since what any genre actually is is a way of reading (or, more accurately, a complex of different ways of reading), different ways of reading constitute different genres—if I may risk a founding tautology.

One of the ways of reading that controls many of the parts of many of the texts usually associated with the literary genres might be characterized as "the tyranny of the subject"—that is to say, much of the information in these texts is organized about the concept the subject, the self, psychology.

This is not necessarily the case with texts usually ascribed to the paraliterary genres. Often, there, we find the subject given relatively little attention. We say, from the literary point of view, that the characters are shallower, or are not as richly drawn—though we are quite used to the flattening out methods occasionally used in literary comedy, parody, or satire. But there's also, in literary discourse, an always-already present disdain for the paraliterary genres. This can be shown by pointing out the above contradiction: While we praise the caricatures of a Dickens or a Mark Twain, we will quickly turn around and criticize a Kornbluth , a Blish, a William Tenn for using equally flattened characters in a story. But in such tales, the character level simply isn't the focus. In such stories, to read for such character depth is blatantly to misread the text—as it would be in, say, Thurber, although for different reasons..

Generally speaking, the kind of attention that we pay to the subject in literature—an attention that, in part, constitutes the way of reading that is literature—has to be paid to the social and material complexities of the object in many of the texts usually ascribed to the paraliterary genres—most specifically in those texts usually recognizable as science fiction.

Because literary critics are so used to talking and writing about the subject, often when they come to science fiction texts they simply are not comfortable yielding up their analytical attention in these new ways, to these new topics.

Now, if that's what you mean by reading paraliterature by a different set of conventions and reading it on its own terms, then—yes—I'm with you. Or, indeed, if you mean reading parliterary texts, with a sophisticated awareness of how the genre's history makes various rhetorical figures signify in their particularly nuanced way, then—yes—I'm still with you.

But even while no text escapes the mark of one genre or another (often a given text must bear several generic marks), no particular way of reading belong ultimately and absolutely only to one genre. The genre field is constantly reconfiguring itself under historical pressures that cause ways of reading to move about and displace each other across what—only if we step way back and squint—can we make ourselves see, from time to time, as severing chasms.

As to slipstream: Well, I find myself smiling.

"Speculative fiction" is the term that once fulfilled that same job until it become so generalized that it no longer meant anything at all—or rather, meant almost everything, so that it was appropriated by all sorts of groups with some really bizarre agendas. I wonder if the same thing will happen to "slipstream"?

RT: The incidents talked about in 1984 precede your professional entrance into academia. The book offers a sometimes gritty look at the life of a writer trying to survive on writing alone. Aside from the financial stability, is the writing life much different as a university professor? And let's not forget that many people are . . . let's say "upset" that writers seem to hole up behind the ivy—is there merit to this complaint, or are there aspects of this culture they may not be considering?

SRD: One of the ideas that underlies much of what I'm speaking of here is what might be called "the fundamental complexity of the recognizable." That is another way of saying that anything stable and enduring—or, indeed, iteratable—enough to be recognized is bound to be complex. This notion is one of the few modern philosophical concepts, by the bye, that actually flies in the face of what old Pappa Plato thought: Plato thought that stability was a simple notion, related to the good and the beautiful. I say, rather, stability is always a matter of complexity. Anything that is stable must be involved in a complex of interchanging relationships—physical, electrochemical, mechanical, economic, social, psychological, or discursive—within the complex of the greater system in which it's embedded. Otherwise it would simply be destroyed and cease to exist. Solids are more complex than liquids, which are more complex than gasses. Universities, rocks, and solar flares are all complex phenomena, because they endure—or because they repeat. We're only beginning to realize what an incredibly complex system what scientists heretofore have called "nothing" is: that is to say, "pure" "empty" vacuum. For one thing, perfuse it with nothing more than gravitational force, and—besides bending—it starts spontaneously belching up pairs of anti-particles here and there throughout . . . ! No, this is not simple stuff. And its intricacy down around the level of quantum foam and six-dimensional Callabi-Yau shapes below the size of the Planck length alone can explain why there's so much of it and its lasted so long—that is, can answer Baruch Spinoza's question ("Why is there something rather than nothing?") in its most recently fascinating form (from novelist and North Carolina newspaper columnist David [The Autobiography of My Body] Guy): "Why, in an infinite universe, is there an infinite universe?"

This insight about the inherent complexity of stability is, of course, the joy and justification both of the material scientist and of the culture critic.

But I seem to be veering away from your question, instead of boring to its center.

What was Goethe's quip? As soon as a man does something admirable, the whole world conspires to see that he never does it again. For a writer to be in a university must mean that, at one time or another, she or he must wonder: Aren't they really paying me not to write?

The process is recognizable—but its ways of holding the writer within it are complex; and, indeed, recognizable. Maybe they could stand a little analysis too.

—Buffalo, NY

November 2000

Click here to buy 1984 at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Winter 2000/2001 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2000

Teresa Porzecanski

Teresa Porzecanski