Robin Fulton Macpherson

Robin Fulton Macpherson

Marick Press ($16.95)

by Peter McDonald

Two things are certain in Scotland in July: midges in the highlands, and tourists in the urban centers. Edinburgh suffers particularly from the latter. But at the far tag end of the Royal Mile, in a little alley, sits The Scottish Poetry Library, an oasis of leafy books amid the welter.

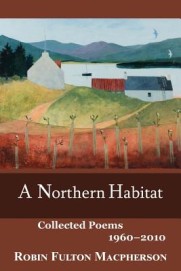

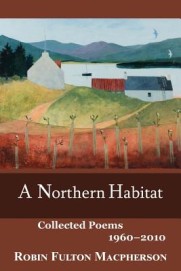

It was there, on a little shelf all by itself, I came upon A Northern Habitat: Collected Poems 1960-2010 by Robin Fulton Macpherson. The name sounded oddly familiar, so I took a seat in that quiet place and read the back page to get acquainted with the work. Of course! This was the Scottish poet Robin Fulton who was also the renowned translator of Tomas Tranströmer, among other Scandinavian poets, long before the reclusive Swede won the big prize. Macpherson had used Robin Fulton as his authorial name for his entire career as poet, reviewer, and translator, and only when he retired from his teaching post, after thirty-odd years in Norway, did he return to using his family name. Since most literary critics will know him as Fulton, I will call him by that more familiar nom de plume throughout.

A Northern Habitat is a wonderful collection, and it deserves wide readership in the U.S. This compendium is chronological by the publication date of his books so it almost serves as a biography of his evolving work as a poet. Born on the Isle of Arran in 1937, Fulton’s early childhood was indelibly marked by the insular world of a Scottish isle bereft of most all the amenities of a burgeoning 20th century: electricity, motorways, household telephones, and much else. Only the German bombers, flying overhead on gloomy nights during the early 1940s to unleash their fury over Glasgow and surrounding factories, brought the modern world’s mighty technological changes to the door stoops of the crofters’ huts of Arran.

Fulton’s fine eye for the natural image was doubtless formed amid this idyllic scenery, set against a hardscrabble childhood under the cold eye of a strict Presbyter father. That dichotomy in his poems, between the simple facts of the natural image and the detached, often messy realities of human existence, is a singular theme that recurs throughout his poetry. Fellow Scottish poet James McGonigal said Fulton’s formative poems seem “lyrical and melancholy, often with a sense of deep psychological disturbance just beyond the edge of his local landscape.” The opening stanza of his poem “Five” captures this frisson:

the dark is never perfect

your free fall will not

be invisible forever–

how deep is the dark?

not deep enough

It is the reader who has stepped off the ledge, of course, and you’re in it like a lead sinker through the whole free fall. Fulton did not include this poem in his collected poems, though many other poems from Tree-Lines (New Rivers Press, 1974), where “Five” first appeared, are included. It is chosen here specifically to capture something else about Fulton’s poems, an exemplar if you will. Many of his poems simply compel you, as here, to read on to the end like a sleuth in search of some meaning to the words so finely conjured. Fulton has noted of Tranströmer’s work: “It is often said that the enigmatic nature of many of his poems is due to the fact that he hides or omits logical connections.” Fulton might well have been describing his own work. From the book, here is the poem “Something Like a Sky” in its entirety:

Something in us has suddenly cleared.

Like a sky.

Like a still-life, alive.

Behind us, our footsteps and voices.

Behind the walls, a wide silence.

The air is white and open, ready for snow.

Each line forms a single sentence, an image unto itself. Stress and syllable create the tension as the poem here, like the sky, opens up slowly line by line. But upon examination, what exactly in us has suddenly cleared? And how does a still-life (of inert common objects) suddenly come alive? Behind us as well are our voices, yet how then are they also wide with silence? This is quintessential Fulton. His poems are compelling precisely because we can so easily become disoriented in them, like a child lost in a thicket. How to get out? Invariably the arresting way out is to be taken in hand by his disturbingly fresh images and led out of the briars into the open to look back and see the poems whole, like the sky. Wide-eyed, we read on.

In a career spanning forty-five years, Fulton has been surprisingly tight-lipped about his work. Indeed, in one interview he seemed to greatly admire Philip Larkin’s response to how a self-effacing librarian from Hull came to write his poems: “Larkin’s brief and glum remark,” said Fulton, “was rather pleasant in the circumstances: he said something to the effect that most of his poems had been written in and around Hull with a variety of HB pencils and that there wasn’t really much more to be said.” There is something utterly refreshing about this sharp observation, as true of Fulton as Larkin, in our gadget-driven age when so many out-loud poets divulge every last fatuous thought via thumb-clicked media.

What Fulton has shared is that he rarely starts his own poems with pencil and paper. Rather they come into his head more as geometric patterns of language where he works out the structure, the images, and the feel of the poem first. Only when so formed into some semblance of a poem does he commit the words to paper. Fulton clearly has a formalist’s regard for the line break and stanza. He admits to re-working his poems once on paper, and it is perhaps here, on the page, that the majority of his poems find their final structure in stanzas, a form which he uses regularly. He has admitted, too, of being fond of mathematics. This geometric temperament perhaps explains the patterning of his poems on the page; they seem somehow tidy in their varying stanza lengths, syllabics, sentence structures, and so on. What makes them so engaging is his almost musical ability to compose his poems in a way that is never obtrusive, never imposed. He has said: “I like arranging discreet little patterns that help to give shape to a poem, without being rigid.”

Sparrows. Brown snow-flakes in a hurry.

Sudden fruit bending a bare bush. Gone.

Gulls, high, falling up, climbing down, slow-

motion debris from a distant blast.

These two opening stanzas of “Those Who’ll Stay” offer a sense of his musical ear. The lines never go slack, instead are bright and precise, yet sound lively with no monotonous metronome. The whole poem ends with these:

Geese who aimed themselves south are now runes.

They breathe the sky of wonder emblems.

Winter, runeless, opens a large eye

on those who’ll stay. His handclasp is tight.

This stark ending remains familiarly enigmatic; Fulton is at heart lyrical, his poems most often falling within an elegiac mode, infused with a wonder of the natural world. They are also often full of a sort of vague haunting—think wraiths on a moor—his obsessions form and unform in a whirl under a conjuring eye that remains elusive. While many poems are penned in the first person, there is often a sense that he is himself a stranger in them, walking through an uncertain landscape, the path ahead shrouded. From “Two Part Invention”:

I was blind, I watched

September: warm breath

of willow-herb . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I was deaf, the birch

woke me.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In the brain of one

migrating swift I

was seen to be whole . . .

Trees, notably, form an important and constant backdrop to Fulton’s poems, perhaps a faint legacy of filling in the absence of trees of so much of Scotland’s wilderness. Says Fulton: “If someone could scan my soul they might well see traces of a fear of chaos and of a panicky unease about large open unmarked spaces like the moors of Sutherland and Caithness.” The lyric, stanza-bound enclosures of his poems provide some of that sought-for comfort, as trees encompass their bounded fields of pasture. In one poem he asks “how many pages are in a tree” as if trees magically contained within their bark not only the pulp of the parchment upon which his poems are writ, but also the living image of the rootedness they impart to his poems.

Some of his poems like “A Photo of Life and Art” and “Postcard” from his more recent work (1988-2010) play with inventive line breaks in more free-form styles, looking ragged on the page but suiting the staccato pile of images. But these are infrequent. While not averse to the longer poem, most poems in this fine book sit well on one page.

For thirty plus years Fulton served as an instructor at what is now the University of Stavanger, in Norway, teaching many subjects in his native tongue, but oddly not English literature. One might call that an academic career, yet Fulton is entirely self-effacing about these years of teaching, always exacting in his modesty, putting one in mind of T.S. Eliot quietly adding up his sums in that London bank while The Waste Land rattled around. Similarly, there’s a delightful disparity between Fulton’s quiet modesty as an expat Scot and his magnificent body of work where his true craftsmanship of language shines through like a blaze.

Some may remember him as editor for ten years of the seminal Scottish poetry journal Lines Review. Oddly, one of Fulton’s first major publishers back in the 1970s was a U.S. small press, New Rivers Press, that apparently had no fixed address, at one time out of Peter Howard’s Serendipity Bookshop in Berkeley (Tree-Lines, 1974), earlier still (the spaces between the stones, 1971) from a P.O. Box in New York City. But the Scottish Arts Council was farsighted enough back then to see the promise of this then-young Scots talent to fund the publications. One might suppose from this that Fulton would have garnered a broader American following. Sadly he is largely unknown. Counting chapbooks, his poetic output stands at under ten volumes, with many other seminal works of translation, as well as worthy works of criticism on Scottish poets. But it is certain that A Northern Habitat will stand the test of time. It is arguably, the most important book yet from a Scottish poet in this new millennium.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

MORE INFO HERE

MORE INFO HERE