photo by Erin Deale Richardson

Interviewed by Simon Wilbanks

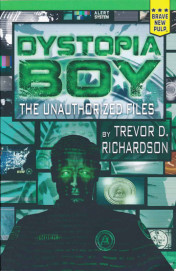

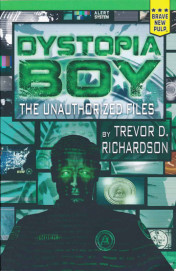

Trevor D. Richardson is the founder of The Subtopian Magazine and the author of Honeysuckle & Irony (Rainy Day Reads Publishing, $16.95) and American Bastards (Subtopian Press, $14.95). His most recent novel, Dystopia Boy: The Unauthorized Files (Montag Press Collective, $19.95), has been described by Underground Voices Magazine as “a road tripping, rebellious adventure into the black heart of a failing republic and an in-your-face hallucinatory romp that brings the traditions of Philip K. Dick, George Orwell, and Alan Moore into one cohesive epic.” I sat down with Trevor for a conversation at a coffee shop in Portland, Oregon to discuss the all-too-real plot points and ideas in his novel.

SIMON WILBANKS: As I finished the last few chapters of Dystopia Boy, a few phrases jumped out at me: “They look for the big doom, the period at the end of the American sentence. Everybody misses the point”; and “The end will come a little at a time, not in one death knell blow. Things start ending as soon as they begin. . . . Watch for signs of the end. Watch for the story behind the story.” This theme of our own ambivalence as the whimper that brings about the end seems to be the real backbone of the novel.

TREVOR D. RICHARDSON: I always say that your only motivation for writing a story should be to write a good story. I don't believe you can go into it with an agenda like trying to change people's minds or spread the word for some cause—anything pedantic like that and people see right through you. But with Dystopia Boy, I broke my own rule. When I wrote this, I had a singular goal in mind: to use your phrase, I wanted to show a world where the ambivalence of the people led directly to their own destruction. Dystopia Boy is not about a zombie war or a robot uprising, it isn't about nuclear fallout or a plague. It's the story of our own laziness in the face of evil taking us down a path that leads directly to the demise of our own democracy. If the world of Joe Vagrant and the Watchers and Audrey and all these characters has any plague, it would just be that people don't do anything about evil until it has become so big and so pervasive that the only way to stop it is to fight and die.

TREVOR D. RICHARDSON: I always say that your only motivation for writing a story should be to write a good story. I don't believe you can go into it with an agenda like trying to change people's minds or spread the word for some cause—anything pedantic like that and people see right through you. But with Dystopia Boy, I broke my own rule. When I wrote this, I had a singular goal in mind: to use your phrase, I wanted to show a world where the ambivalence of the people led directly to their own destruction. Dystopia Boy is not about a zombie war or a robot uprising, it isn't about nuclear fallout or a plague. It's the story of our own laziness in the face of evil taking us down a path that leads directly to the demise of our own democracy. If the world of Joe Vagrant and the Watchers and Audrey and all these characters has any plague, it would just be that people don't do anything about evil until it has become so big and so pervasive that the only way to stop it is to fight and die.

SW: Let's talk about The Watchers. Where did they come from? Were they influenced by Edward Snowden and the NSA?

TDR: Believe it or not, my book was already finished before the Edward Snowden thing happened! For the folks at home, Dystopia Boy is narrated by an agent at a fictional (at least I hope it's fictional) federal surveillance cabal called the Watcher Security Agency. Through an elaborate network of hidden cameras, satellites, tracking programs inside the Internet, bugs in our appliances, cars, gaming systems, phones, etc., they watch us and analyze everyday Americans for undesirable behaviors. These agents are implanted with microscopic chips in their brains and along the optic nerve that record and process all information that they view and wirelessly upload it to a central server. That one element, commonly referred to as the “Thought Chip,” is what makes this story science fiction. Nearly everything else, apart from the fact that it is happening in the near future, is pretty well grounded in reality.

SW: So well grounded, in fact, that parts of it began to come true before it was even published.

TDR: You're right. When the story broke about Edward Snowden my gut sank. I didn't think about privacy or unconstitutional behaviors; my first thought was, “Aw, man, now they're going to think my idea was just ripping off this news story.”

SW: I thought you were going to say your first thought was that you called it and were proud of yourself.

TDR: Maybe I should have, but I just felt like it was going to affect the integrity of what I thought was an original idea. Then, not too long later, the story breaks that by 2015 unmanned aerial vehicles, “drone planes,” would be legal over American soil. Another image I came up with for the book for no more academic purpose than I thought it seemed super creepy.

SW: So talk more about how you came up with the idea for these Watchers. It sounds like you've been working on this for a while.

TDR: I actually started writing this book in 2007, but quickly set it aside because of Obama. It was still the Bush years and the cultural vernacular of the time was laced in conspiracy talk: 9/11 was an inside job. The Patriot Act will destroy freedom and privacy. Guantanamo Bay. Torture. That quote from Ben Franklin about sacrificing freedom for security and deserving neither. Patriotism versus idealism.

For a guy that writes the kind of stuff I write, the atmosphere of America was palpable. Only one problem. We were already into the primaries for the next election and this book idea was nowhere close to finished. I saw me completing a book that was all about America eating itself from the inside out and trying to publish it in an America high on a climate of hope and “Yes, we can!” I knew Obama would win, and I knew it would mean a dry spell for my particular brand of dystopian fiction. So I set the book aside and let it marinate for a few years. When I felt it was time to revisit the novel, I started completely over and was much happier with the result.

SW: It sounds like you felt things would go back to the way they were if you just gave it enough time. You seem to be saying that the ideas of the first draft were influenced by the Bush administration and this new book, the version you published which is filled with concepts and echoes from more recent events like the Occupy Movement or the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia in 2011, came out of what I guess you could call the Dystopia of the Obama Administration.

TDR: It wasn't an assumption, I knew it. It's the cycle. And it is a cycle because there has been no fundamental change in decades. That's the message of Dystopia Boy, things are getting worse because each iteration of our government is like making copy after copy for so long that the image is breaking down. Most post-apocalyptic stories have America dying from some radical disease or some violent trauma, but we're really just dying from Alzheimer's.

SW: Interesting analogy. So I want to ask, did you get the idea for the Watcher Security Agency from the conspiracy talk of the Bush years? What was the source of this modern, Orwellian organization?

TDR: Believe it or not, it was my parent's minivan in high school that first gave me the idea.

SW: How does that work?

TDR: In the early 2000s, my folks bought a new van and it was white—this was in addition to the white Jeep Cherokee we already owned. So we started realizing these white cars were everywhere and I made this joke about it being a cheap way of policing the roads. Like, when you drive, if you see a car coming towards you from a ways off that might be a squad car or whatever, you slow down. You can't help it, it's practically reflex. The idea was, what if it was being done deliberately? Flood the market with white cars that people might think are cops, make them pay their own money to get these things on the road, and then reap the rewards.

Then, a few years later, we all start hearing these rumors about the “HD changeover.” You probably remember this, the idea was that broadcast networks were going to be changing to high definition and, if you wanted to be able to receive the signal, you had to either go buy an HD television or this little converter box. I got to thinking, “Hey, wouldn't it be crazy if these new appliances had little hidden cameras and audio bugs in them?”

SW: You're saying that they were making us use our own money to fund their police state for them. The costs of putting cameras into every home in America would be astronomical, but the cost of getting some corporations to agree to put these things into their equipment would be minimal and they might even turn a profit since all of us television addicts are going to rush out and buy the hardware whether we like it or not.

TDR: Yeah, exactly. That was the gag. From there it was just a few short steps to imagine who would be on the receiving end of these transmissions and, once I had these Watchers in mind, I just had to figure out what the story they were watching would actually be about.

SW: Which brings us to the elements of your story that impressed me the most. Your book starts out with an interoffice memo from the Watcher that has just finished transcribing the “Thought Chip Record,” that is the audio-visual files stored digitally in their server, into a hardcopy file. I remember thinking I was very clever for realizing that the book in my hands is meant to be a pirated copy of that transcript this Watcher is so carefully trying to keep secret. The first page, in fact, is a cover sheet for a Top Secret document and there are all sorts of little clues planted throughout the story. What gave you the idea to try to give a plot-based explanation for why your book exists?

TDR: I've been asked this a lot and if I had known that people were going to fixate on the choices in construction that went into this book rather than the story itself, I might have tried to do a better job of it. But, as it stands, the simplest explanation is to give some credit to Chuck Palahniuk.

SW: Author of Fight Club.

TDR: Yeah. Do people not know that? Okay. Well, Chuck obviously wouldn't remember this, but we spoke briefly at a reading in Dallas that he gave in 2005 and I came away impressed by one concept above all others. He said he liked to use “non-fiction forms” to tell his fictional stories. Maybe the easiest example is his book Survivor, which is supposed to be the transcript of the flight recording taken from the black box of a hijacked plane. The narrator, piloting the craft, is telling his story, out loud, to the flight recorder and we are supposedly reading it after the fact. That extra element of breaking the fourth wall really inspired me and I wanted to try to come up with my own original non-fiction form. It went so far that I not only created a government agency that might have a printout of some strange occurrences, but I also needed to come up with a reason why they would go to print when things would typically be stored digitally. This gave me the idea to start the book out with Joe, the protagonist and leader of a hacker revolution, infecting Watcher headquarters with a virus that makes their equipment and their operating system unreliable.

SW: How much of this drive to create your own “non-fiction form” led to the different ways that you played with narrative point of view?

TDR: I'm not the most sophisticated writer; most of what I do is simply because I think it would be neat. In establishing a new non-fiction form in the narrator of Agent Anders, the Watcher that spies on Joe, I realized that I had effectively put a face on the classic disembodied third-person narrator. I didn't plan to do it, but once I realized it happened I wanted to really play around with that. Technically, I would say that Dystopia Boy is a first-person narrative. Even when you are reading the “Joe does this” or “Joe feels that” parts of the book, it is still coming from the mind of Anders himself. Yet it seemed kind of interesting to me to think that whoever the classic third-person narrator was, even if you just imagine it to be Charles Dickens himself or whatever, that it is just a first-person narrative insofar as it is coming from the mind of the guy telling the story.

This made me decide to give Anders a bigger role and I wound up with two distinct storylines: the past that Anders was watching and the present story of what was happening at the Watcher Security Agency during this one crazy day.

SW: Yes, but as the story goes on, you have Anders download Joe's entire file into his Thought Chip, an apparently dangerous procedure that results in him experiencing the memories of Joe from his point of view. In short, your first-person narrator who is telling a story as the third-person narrator is forced inside of the story and becomes its first-person narrator. The fact that this is actually accomplished and not totally confusing is an achievement in itself. But you don't stop there.

TDR: No, later on Joe leaves the past storyline and becomes a kind of ghost in the machine, a technological glitch that shows up as a waking hallucination and keeps Anders from being able to do his job. So, I guess that would be an example of the third person invading the first instead of the other way around. This cross-over between the two storylines got really fun when I had the idea to have what Anders calls “Phantom Joe” lead Anders through some of the files. I imagined it like Virgil leading Dante through the rings of Hell in Inferno, though a book critic compared it to the Ghost of Christmas Past leading Ebeneezer Scrooge through the visions of his younger years. That might be more accurate.

SW: So let me get this straight. From a remark from the guy who wrote Fight Club, you came up with the Thought Chip and the surveillance files. Through the glitches and hacking of the Thought Chip, you managed to come up with all sorts of story-based excuses to turn all the rules of narrative perspective on their head, and you just made it all up as you went along? Was any of it planned?

TDR: The only thing I had planned was that I wanted one of the later chapters to wind up being a loose take on the first story I ever published. It was called “Safety Factory” and it was published by Word Riot in 2005. I had that as something I was aiming at and, being that it pertained to alien abduction and paranoia, it inspired a lot of Joe's misplaced fear of aliens out to get him. Otherwise, my usual love for creative characters trying to make the world a better place was what I had to guide me and I just kind of followed these characters where they wanted to go.

SW: One last question.

TDR: Better make it good.

SW: The story of Joe's life, an abused kid running away and becoming a wandering musician, eventually becoming the leader of the Hack War, and a lot of the stuff in there about “the power of dreams,” Joe's drug use, and talk about creativity as the hope for our future . . .

TDR: I don't sense a question coming on.

SW: What I mean to say is, how much of that do you actually believe?

TDR: I get asked this a lot. To put my own spin on an old feminist joke, if it's the businessmen that have brought us to where we are now, maybe it's time for the artists to have a turn at the wheel. Here in Portland, there is a strong art community and with it come signs of how to run a better society. The artist can work for the sake of the work itself. The artist can think outside of their own mind and opinions because that is the only way to create something new. Most artists are liberal-minded, more accepting of diversity. I really do believe that if more people were pursuing self-expression in some creative field then we would watch a lot of the old constructs, traditions, and assumptions melt away, one person at a time, until they sounded as outdated as the cotton gin or Jim Crow Laws.

There is another message in this book that I didn't know I put there until it was all over: the American Revolution never ended. We have to fight it every day. However, we can't fight it with guns or violence anymore. We can't really even fight it with organized protests because they're too easily ignored. What we need is a new awakening, a call to intellectual action, people reassessing and taking responsibility for their own minds. Stop asking how everyone else is wrong and start asking yourself how wrong you are. Then lead by example. Joe and his band start a revolution just by playing music and helping to feed the poor—that's it, they use art to rebuild the world around them and they don't ask for permission or support from anyone but themselves. It might sound naïve, but when I look at how my pursuit of writing has taken me from a staunch conservative, religious bigot to a liberal, hippie-Commie that I am today, I can personally attest to the life-altering power of art, and I hope more people find it.

Click here to purchase Dystopia Boy at your local independent bookstore

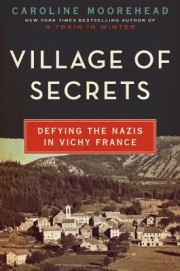

Caroline Moorehead

Caroline Moorehead

Interview by Berit Ellingsen

Interview by Berit Ellingsen

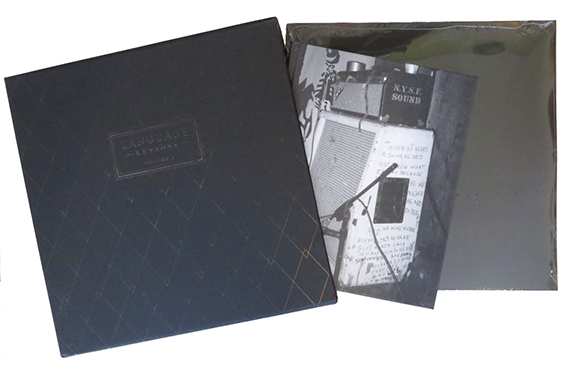

Marquard Smith

Marquard Smith

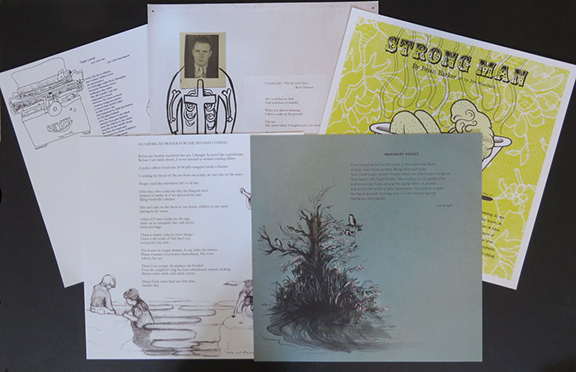

Lisa Gluskin Stonestreet

Lisa Gluskin Stonestreet