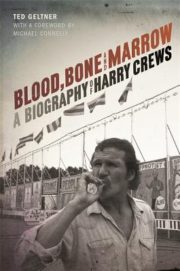

Ted Geltner

Ted Geltner

University of Georgia Press ($32.95)

by Patrick James Dunagan

The life story of novelist Harry Crews is one of triumph and defeat, with defeat usually overwhelming triumph. Not much about Crews is pretty, but it is at times courageous, even if most always raw in accompanying detail. With a lifelong devotion to shocking others, Crews courted the extreme with the sort of measured pace by which most might pursue a regimen of daily exercise. His life is a remarkable tale of sui generis hardscrabble southern gothic literature. Book after book by Crews is filled with bizarre tales of circus-freak characters and assorted weirdo personalities inspired from underground backwaters of Americana. While his earliest work is all fiction, he was arguably writing at his best when he later dived into exploring autobiographical material. Ted Geltner’s Blood, Bone and Marrow delivers the full goods on Crews, the son of Georgia tenant farmers who was determined to succeed despite the handicaps of ill luck, alcoholism, and an impoverished upbringing.

Throughout his life, Crews remained uncertain regarding his true father’s identity. In 1937, he wasn’t yet two when his mother Myrtice’s first husband Ray suddenly passed away. Six months after Ray’s funeral Myrtice married Ray’s just-recently-divorced brother Paschal, who immediately took on the role of father to Crews and his brother Hoyett. It wasn’t until many years later that Crews would come to learn that the man he grew up knowing as his father was in actuality perhaps his uncle. By all accounts Ray had been a devoted, dependable, hard-working husband, while Paschal displayed predilections toward alcohol and the wild behavior similar to that which Crews would later find he was himself prone.

At the age of sixty, Crews was still seeking out his ninety-year-old aunt Eva to learn about “the events surrounding his birth and the tale of two daddies” and to ask her “whose blood I got in my veins.” The unsettled nature of the exact sequence of Myrtice’s intimate relations with each of the two senior Crews brothers would eventually spill over, disrupting the relationship between her own grown sons. As children, “Hoyett wielded his power” over Harry as the elder sibling; it was a mismatched balance of power Crews never forgave. As adults, Hoyett “viewed Harry’s writing with disgust and saw his little brother as a godless drunk” while “Harry thought Hoyett a mindless bible thumper.” After Mytrice passed away late in life, the two brothers had a falling out over details regarding the handling of her death and never saw or spoke to each other again—one of the final acts in a series of obstinate refusals Crews had a lifelong habit of committing. Crews relied upon his healthy inclination towards such self-willed stubbornness to achieve everything in his life.

Nothing ever came easy to Crews. At the age of five he was struck with polio: one day his legs just started to curl up and kept on going until his feet tucked up under his thighs, leaving him bed-ridden for weeks and with a lifelong limped posture. Doctors told his mother he would never walk again, yet soon enough he began to drag himself around the floor, eventually gaining use of his leg—just in time to suffer another life-threatening event. Playing with cousins during hog butchering season, he fell feet first into a vat of scalding water when the carcasses of freshly slaughtered hogs were being placed to loosen their tough hides for scraping. If not for the fact that his head stayed above the water, bobbing about amongst the hogs, this would have no doubt ended his short life. As it was he lost the skin from the majority of his body and once again spent weeks bed-ridden. During these youthful periods of incapacity, however, Crews developed a penchant for exploring his imagination; spinning tales, he’d entertain himself and any family and friends willing to lend an ear.

Upon graduation from high school Crews enlisted with the U.S. Marines, who overlooked the fact that he’d been refused the day before by the U.S. Army due to the damage childhood polio had inflicted upon his leg. Crews intended to be sent to fight in Korea as Hoyett had a couple years previously, so that he too might prove his manhood in combat, yet three weeks into basic training the Korean War came to an end. Crews instead served three years in Florida performing airplane maintenance. It was hardly the glory-making debut of his manhood which he’d envisioned, however his time in military service did get him out of Georgia for the first time and opened the door to higher education, which eventually led to his lifelong teaching career and gave rise to his literary inclinations. Yet weeks into his education in Florida courtesy of the GI Bill, Crews was told that given his low test scores a college education appeared an impractical decision. Crews characteristically refused to quit, determined that if he wasn’t kicked out, he’d buckle down and manage to find his own way through. But first he took an impromptu cross country motorcycle trip West, “yet another quest for self-discovery” to broaden his sense of the world beyond Bacon County, Georgia.

Crews graduated from the University of Florida having studied writing both in and out of the classroom with the Southern gentleman writer Andrew Lytle. It was also the University of Florida to which Crews later returned and remained throughout his decades of teaching. Yet Crews himself never studied writing at the graduate level, holding his Master’s in Education instead; when he had applied for entrance to the graduate creative writing program he was denied. This reinforced his tendency to self-identify with the “outsider” status which became his trademark, both in and outside of the university. It was clear from his lifelong outlandish personal behavior, wearing his hair in a Mohawk and sporting numerous tattoos later in life, that he cherished keeping himself wild and fierce looking.

Determined to be a writer, Crews forced his artistic development through sheer will power. His ultimate self-taught lesson was to deconstruct Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, devising “a project for himself in which he would take apart a novel as one would a car, then put it back together again in order to discover, with his own senses, how it worked.” Crews in effect “reduced the book to a series of numbers: How many characters were there? How many days, weeks, years did the action take? How many cities? How many children, adults, women, mean? On what pages were the climaxes, the twists in the story?” It wasn’t an organic approach but it allowed the means for him to develop his own method of getting the writing done.

Early on in his teaching, after one student turned in a story containing an oral sex scene, Crews read it aloud to the class, abruptly stopping to ask the student whether or not she had “ever given a blow job” before declaring: “Never, NEVER, write about something you’ve never witnessed or done.” Geltner locates similar examples throughout Crews’s life, from his youthful dalliances with death, to his military career and motorcycle adventure, to his experiences amongst academics and within the publishing world—where time and again Crews followed his own rule, always writing only about that with which he had firsthand experience. If life became not particularly exciting, Crews was always sure to shake things up. He continually picked up hobbies, whether Karate, amateur weight lifting, or training hawks, and he would later shape many a novel around them. In addition, he was restless when not writing and prone to getting into violent fights, especially during ever frequent drop-down-dead drunken states—all of which bled directly over into his work.

Geltner came to know Crews firsthand in the final years of the author’s life, and he relates anecdotal tales of visiting Crews at home and driving him around on medical errands. These vignettes are dropped in throughout his narrative, and the end result is a well-rounded, full representation of Crews equally from all sides. There is his devotion to one woman, despite divorce and his flagrant affairs, some long-standing in nature; the rockiness yet steadfastness of his friendship; his failures as a parent; his steadily successful pursuit of greater financial triumph in both the literary world and the Hollywood writer’s market; and his associational brushes with celebrities such as Sean Penn and Madonna. Geltner also provides a thorough exegetical overview of all Crews’s writings, from novels to journalism to his attempts at writing for the stage and screen. In Blood, Bone, and Marrow, the life of Harry Crews is presented in all the hard-knuckled glory he’d desire, while also leaving his faults and weaknesses left truthfully exposed.