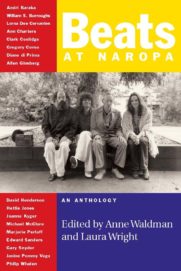

Edited by Anne Waldman

Edited by Anne Waldman

and Laura Wright

Coffee House Press ($15.95)

by Peter Conners

“The poet archivist represents a community of memory that predates church and state and, if we play it right, will outlive them. The Tewa Indian anthropologist Alfonso Oritz said that rather than seeing the tribe as a step in the evolution toward the state, we could see the tribe as an alternative to the state. Tribes, particular communities of memory, act against the vast, homogenizing fog of amnesia that is the state.”

Steven Taylor—poet, musician, ethnomusicologist, and longtime faculty member in Naropa University’s Department of Writing & Poetics—closes Beats at Naropa with this bold declaration, one that could serve as the unifying thesis of the collection. The anthology collects talks and interviews culled mainly from the voluminous audio archives of Naropa University’s writing program. Founded in 1974 by poets Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman as a place to blend contemplative practice (namely, Buddhism) with creative writing, the program goes by the memorable name The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. [Disclaimer: I attended Naropa’s MFA program for one semester in 1995 and have since returned as a speaker to the campus on one occasion]. Ginsberg described the original mission of Naropa’s writing program as “a way of teaching meditators about the golden mouth and educating poets about the golden mind.”

As paterfamilias of the school, Ginsberg gets his say throughout this collection, as does its presiding spirit Anne Waldman, who co-edited the book with librarian and Naropa alumna Laura Wright. Many other heavyweights of the Beat Generation also speak through its pages: William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Gary Snyder, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, among others. However, it’s the lesser-known figures of the Beat scene that make this book a valuable addition to the library of Beat commentary. After all, despite the sensationalized legacy often tragically fulfilled by many of the Beats, the numerous writers who could fit under the label “Beat” (whether they like it or not—and many do not) were also masters of that old fashioned pastime: conversation. Genius bullshitters, intellectual street-hustlers, blunt shamans, yarn-spinning revolutionaries—these folks knew how to talk and they did it, sometimes all night long.

Diane di Prima is one of the sharp, active, under-appreciated writers who shine through in Beats at Naropa. In her July 9, 1997 talk, titled “By Any Means Necessary,” di Prima encourages students to use “whatever you’ve got, whatever comes to hand, to get your work out.” She goes on to recount her role as a poet and publisher over a 40-plus-year period, and while her talk is a personal account, the cumulative effect is a history of small press and underground publishing in late 20th-century America. She describes the process of having artists “draw straight onto the mimeograph stencils with a stylus, and that would be the cover of the issue” for The Floating Bear, a magazine she co-edited with Amiri Baraka (who was, at that time, LeRoi Jones). She also joyously recounts how one of her “biggest kicks” as a publisher was making broadsides because “you could put it up any place—go out with a pot of glue or a staple gun, and start sticking it up wherever you wanted—really getting the word out, or giving it away free…” To those of us who tweet, blog, and otherwise “post” frequently, this process may seem tedious, but this is where it all began.

David Henderson’s in-depth reclamation of the life and poetics of San Francisco poetry legend Bob Kaufman is another valuable contribution to Beats at Naropa. While Kaufman’s name does appear in various Beat histories, a casual student of the scene could easily miss him. Henderson seeks to correct this omission by placing Kaufman firmly into the lineage of West Coast jazz poets and guiding presences that have forged that city’s reputation as a cradle of bohemian culture. Like Baraka, Kaufman was also one of the few African American poets who had a strong presence within the Beat community. Kaufman spent years in self-imposed silence (he literally didn’t speak for years), and died destitute, having lived in various rundown SRO (Single Room Occupancy) hotels in San Francisco.

Other entries in this book that have unique value to Beat scholarship include “Women of the Beats” (a panel featuring Hettie Jones, Joanne Kyger, Janine Pommy Vega, and Anne Waldman), “An Interview with Edward Sanders” by Junior Burke, and Philip Whalen’s enlightening explication of the eco-poetics of Lew Welch via his poem, “Springtime in the Rockies, Lichen.” As with many poets of the Beat generation, Welch’s contribution is in danger of disappearing from the histories. However, Welch also carries one of those haunting, epic backstories that both adds to and detracts from his legend: on May 23, 1971, he walked into the mountains near Nevada City with only a 30-30 rifle and was never seen again. (He was camped near Gary Snyder’s house at the time, so it was left to Snyder to discover the suicide note.)

If I were to pick a nit with this anthology, it would be with the book’s overall structure. In a promotional interview for Beats at Naropa, Waldman states that the editors organized the collection “thematically rather than chronologically,” following William Carlos Williams’s vision of a magazine as “all these bedfellows in the same bed.” Yet a thematic structure is hard to discern. The book is thematically tied by the nature of the speakers and their subjects, but one suspects that deeper, more coherent themes are lurking in the annals of the Naropa archives. This lack of tight thematic focus makes the “conversation” of these fascinating intellects that much more engaging, as if we are at the best cocktail party in history; however it often leaves the reader wishing for a more immediate connective thread to tie the book together. It would also have been helpful to have the dates of each talk provided at the start rather than having to hunt for it at the back of each section, because ultimately—as with di Prima’s view of online publishing as it relates to her own experience—it does make a difference when these talks happened. In computer years, 1997 (when di Prima gave her talk) might as well be 1969 (when she was mailing out her “Revolutionary Letters” to the Liberation News Service).

These structural quibbles are, however, small in comparison to the ultimate value of Beats at Naropa. If, as Steven Taylor writes, “The poet archivist represents a community of memory,” then Waldman, Wright, and the Naropa creative writing program as a whole have here emerged as valuable and responsible presenters of the collective Beat ethos. Given the wealth of material in Naropa’s archives, one can only hope for future cullings such as this.