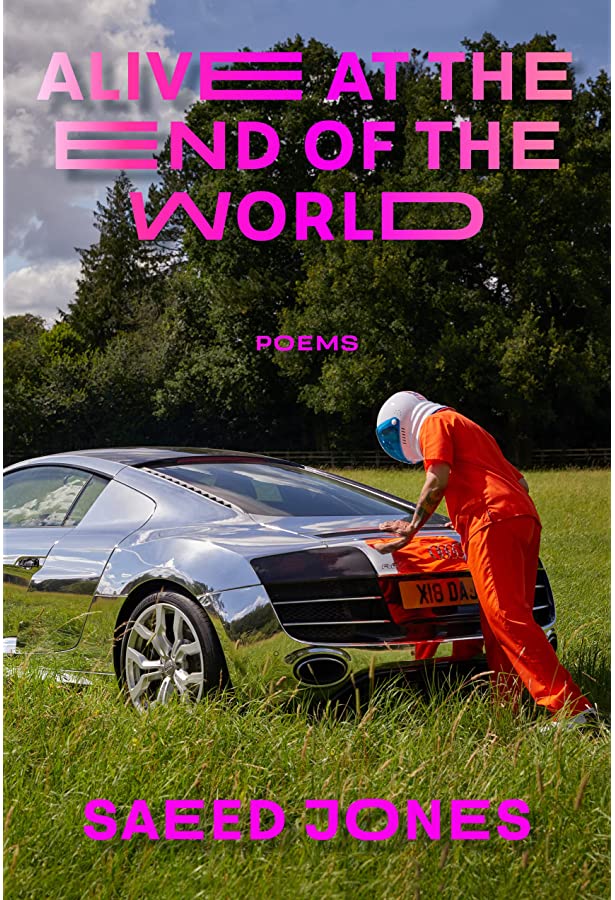

Saeed Jones

Coffee House Press ($16.95)

by Walter Holland

Saeed Jones’s latest book of poetry, Alive at the End of the World, is an outpouring of anguish, grief, and anger. It’s also an outward-looking commentary about racism and the performative pressures placed on the Black artist in America to meet white expectations and assumptions.

Jones’s debut came in 2011 with his chapbook When the Only Light Is Fire (Sibling Rivalry Press). It was followed in 2014 with his full-length collection Prelude to Bruise (Coffee House Press), a beautifully crafted account of his boyhood in Texas and his life growing up as a young queer Black man. The rich lyricism of his work, with its mix of earthy imagery, explosive violence, and sensuous eroticism, portrayed a world of family, country life, pervasive racism, and trenchant inner conflict.

Jones is part of a generation of queer poets of color who have revitalized and reshaped American poetry. In recent years, this group has been nurtured by the efforts of progressive MFA writing programs and writers-of-color-focused organizations. One of these organizations is Cave Canem, established in 1996 by Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady, which seeks to counter the underrepresentation and isolation of African American poets. In like manner, Lambda Literary created its Emerging Writers program for LGBTQ+ authors; these talented poets were also embraced by the small-press publishing world, which made a concerted effort to promote more diversity. Jones joins the likes of Danez Smith, Donika Kelly, Justin Phillip Reed, Taylor Johnson, and Jericho Brown—I could go on—all queer Black poets of distinction.

Alive at the End of the World is a departure from Prelude to Bruise. It has the tone of a jeremiad, a long lament and outcry of informed complaint that is sharp, direct, and chilling. It harbors angry indictment and accusation. It is the work of a maturing poet, too, and perhaps a transitional work: Jones has moved from the subject of his boyhood to the volatile racist politics of the here and now, as well as his worries for the future.

These poems speak of a constantly unjust and fearful world. Jones weaves together scalding social commentary with everyday personal experiences, uncovering the tense undercurrent of racial conflict in every facet of Black life and the psychological wounds it inflicts.

The title poem, really a series of poems of the same title, offers a fitting overview of this formidable project. The first poem begins:

The end of the world was mistaken

for just another midday massacre

in America. Brain matter and broken

glass, blurred boot prints in pools

of blood. We dialed the newly dead

but they wouldn’t answer.

Inequities and violence are casually understated, but their brutality is clear beneath the dismissive tone of the final dialogue:

With time the white boys

with guns will become wounds we won’t

quite remember enduring. “How did you

get that scar on your shoulder?” “Oh,

a boy I barely knew was sad once.”

And it’s not just the most tragic violences that define these end times. In “Sorry as in Pathetic,” Jones describes a white woman on a street walking “right through” him to get to “her next spike-heeled hour.” He waits for the woman to turn and apologize, but soon realizes that her violation of his personal space will not be acknowledged; she doesn’t even “see” him as being there. He closes the poem with the description of another tense encounter, and the sad fallout that adds weight to the title:

once I was lost on a late-night street

and when I asked

the woman walking just ahead of me for help, she screamed

“Oh, god!” and clutched her purse the way the night holds me.

I told her I was sorry, then felt sorry for saying sorry.

I think of that woman often; I doubt she ever thinks of me.

Jones’s language displays a wonderful musicality and a gift for metaphor. In “Date Night,” he contemplates his mother crying out in her sleep for her brother, his uncle, whom she wishes still lived near her, as though only he could give her comfort through his solid masculinity and paternal strength. The poet is hurt by his mother’s yearning—though he is perpetually available to her, he cannot be who she wants—and this suppressed inadequacy apparently gets voiced aloud while Jones sleeps with a lover. Here is how Jones transforms this pain into poetry:

When a Venus flytrap

flowers, the two white blossoms sit atop a very tall

stalk. Green teeth way down at the bottom. It’s trying

to avoid triggering its own traps. It’s trying to keep

the bees it needs for pollination away from its own traps.

I’m most dangerous when I’m hungry. I’m most hungry

when I’m hurting. Seems like I’m always hurting. Nothing

but teeth. Nothing but the same words calling out to me

in my sleep. Grief asking its ghosts not to leave. Please.

It’s not up to me when I get to stop crying. Or hurting.

Or holding memories in my mouth, gentle as bees

I promised not to eat, but oh, the hurt is so sweet.

In a way, this poem serves as an ars poetica as well as a trenchant personal narrative. Jones has tried to resist the temptation to eat of the fruit of grim knowledge—not of something as simple as good and evil but of racist hatred, of maternal rejection, of all the many slings and arrows that Black men in America face daily. But as a poet, as an artist, he is compelled to eat of this stinging truth—and equally compelled to make from it the sweet honey of verse.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023