by Greg Bem

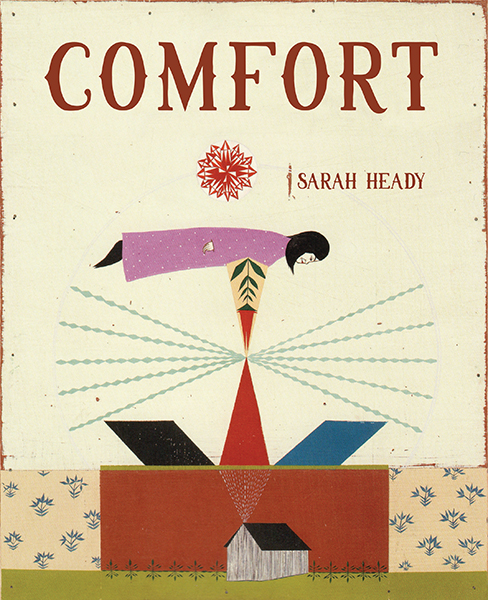

Sarah Heady’s newest poetry book, Comfort (Spuyten Duyvil, $16), is a marvelous amalgamation of found material and poetic investigations of history and place. Heady’s work, as demonstrated in her previous collection Niagara Transnational (Fourteen Hills, 2013), often finds embodiment beyond the self, using poetry as a conduit for collective voice, cohesive culture, and critical inquiries of the world around us. In Comfort, the poet turns her gaze toward an important resource for women a century ago, a late-19th to mid-20th-century magazine of the same title. But the book is far greater than an archival gathering of texts; Comfort strives towards a deeper love for archives and a deeper commitment to cultivating and maintaining beauty through timeless expression. In this new book, Heady steps forward with a new and refreshing history of American women and the world surrounding them, and the result illuminates not only the past, but our own tremulous moment.

Greg Bem: Let’s start with the title, Comfort. As you’ve outlined in an afterword, the magazine of this title catered to “rural housewives” and served multiple purposes, from marketing snake oil to responding to the isolation of women throughout the U.S. How did you discover the magazine, and what was its role in crafting this collection?

Sarah Heady: Thanks, Greg—I’d love to tell the story of how Comfort came to be. During the summer of 2013, I spent a month at a residency in Nebraska called Art Farm. Ed Dadey, the residency director, was born in the farmhouse on the property, and he mentioned to me that the attic was full of decades-old newspapers and stuff, and that I was welcome to paw through it if I wanted. So one day I crawled up into that sweltering attic, and there I found a pile of musty, crumbling periodicals called Comfort. It seemed to be akin to Ladies’ Home Journal—a very gendered and “fluffy” kind of publication, but one that nonetheless gripped me because of its age. The issues that were salvageable I brought downstairs and started reading and photographing, so that I could continue to study them without further damaging them. I didn’t do this in an exhaustive or systematic way, just tried to capture the pages and pieces that were most evocative to me.

A few months later, I began examining those photographs and working with the found language I had captured. The source material took many forms: advertisements, advice columns, serialized fiction, sentimental poetry, recipes, and tips on housekeeping, farming, gardening, etc. I would let my eye wander over the text and pull out fragments of bright or evocative language, and with them I would weave these dense, imagistic prose poems. Eventually I sought out other primary and secondary sources, mostly about the settlement of the American prairie, and bits of found language from those also ended up getting woven in.

I should say that about half of Comfort is composed of non-found-language poems—some of which I had written even before going to Art Farm but which came to feel like they belonged in the project because of their rural setting and their circling around questions of partnership, domesticity, and solitude.

GB: Can you talk a little bit about moving from the exploratory phase to intentionally creating a book? When did you know this work was going to become a book-length project—or was it certain from the beginning?

SH: Not at all! It took several years. The oldest material in the book is from 2010 and the newest from 2015, and it was not clear for much of that time that I was writing a single book.

I definitely want to mention that I created Comfort within the bounds of my MFA program at San Francisco State University. Every stage of the project’s generation and discovery and refinement was supported by the courses I was taking, my teachers and classmates, and what I was reading. The first set of poems that became the kernel of Comfort was a project for an amazing course taught by Donna de la Perrière called “Mad Girls, Bad Girls: Writing Transgressive Female Subjectivity.” That was in my very first semester of grad school, and they eventually turned into a chapbook called Corduroy Road. A few of the pieces in that chapbook were written prior to starting the program, but grouping those poems for Donna’s class was the first time I had a sense of a project I wanted to keep writing into.

The summer following my second semester was when I went to Art Farm. So then I had all the Comfort magazine material in addition to this first set of poems, which started to feel related to the found text experiments I was doing not only with the magazine stuff but with other primary and secondary sources about the Midwest prairie. I continued to scope the project, as it were, figuring out what belonged inside the frame and what didn’t. In Barbara Tomash’s transformative workshop “Imagining the Book,” I gave myself the prompt to create a kind of abecedary in which I listed, for each letter of the alphabet, all the nouns that came to mind for the world of Comfort. This compendium of both sensory elements and abstract concepts became almost like a film or TV show “bible,” a guiding outline for the book—if such a thing could exist for fragmentary, nonlinear, non-narrative poetry.

After a time, when I had a sense of this world, I used every grad school assignment to write into Comfort as I was conceiving it—whether doing experiments with the found language I’d brought home from Art Farm or refining the non-found pieces. Truong Tran’s class on the prose poem was especially important for refining the form of the found text poems. I’d like to think my work itself is concise and concentrated, but I’m a maximalist in my process—I overgenerate and then go through many, many rounds of culling to end up with the final product. At its longest and muddiest point, Comfort was a 400-page compendium of fragments that I sliced and diced and reordered and shaped with the help of many readers, until it ended up as a normal 86-page book. I consider it a book-length poem rather than a collection. And it turned out to be my MFA thesis.

I don’t say all this to imply, by any means, that an MFA is necessary to write a book, but I always appreciate when artists are clear and forthcoming about the material and social and intellectual conditions surrounding their process.

GB: Visually, Comfort has a rhythm to it; there is a wide range of the poems’ shapes and sizes. Formally, the text rotates between hefty blocks of prose and chiseled, scattered verse. The prose often centers on long lists—not exclusively lists of images or objects, but also states of being, relationships, observations, and consequences. The lineated verse, in juxtaposition, feels more personal, more human, composed of specific voices. Whose voices can be heard in Comfort? Should we be listening to, or for, someone in particular?

SH: It’s true that there are a few different registers of voice in the book, which tend to correspond to shifts in form. The prose blocks are where most of the found language lives, and because of the multiplicity of sources I used, they have a listing quality that is meant to imply a sea of individual voices/experiences/perspectives/moments that have been collapsed or coagulated or sedimented so that they become anonymous and collective. Most of the prose blocks are also literally missing a subject (e.g., “is running a small piece of sand soap through the grinder. is dipping brooms in hot suds. is tying a cord around a glass stopper.” I borrowed this specific form from Pattie McCarthy’s Marybones, although in her book the word “Mary” precedes each prose block and therefore attaches to the following barrage of predicates. “Mary” contains multitudes of characters held by that name and explored in the book: the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, Mary Tudor, Mary Shelley, Mary, Queen of Scots, and millions of regular, non-famous women named Mary who have lived throughout time. In Comfort, the missing subject is meant to suggest even further the anonymity of women in the historical record. C.D. Wright’s technique of collaging documentary fragments, as exemplified by her books One Big Self and One With Others, was another big influence on Comfort as well as on Halcyon, the libretto I wrote about the history of a defunct women’s college.

The lineated verse in Comfort, as you note, has a more personal or singular tone and usually is written in the first person, though I can’t say there is a particular individual I had in mind—perhaps one voice rising out of the sea of collapsed prose voices, and yet still just another farm wife we don’t know a whole lot about. The only “character” per se in the book is someone I call the Seer, a sort of mystical figure based on a historical woman named Susan Gavan, known as the “Aurora Witch” to ghost-hunter-types. She was not a witch, just a woman who died young and inspired rumors much after the fact because her grave is isolated from the rest of the dead in the cemetery in Aurora, Nebraska. But in Comfort, the Seer is indeed a wild and powerful woman who sort of pulls the farm wives away from domesticity, into a more feral state of self-knowledge. And her voice comes through—mysteriously—at various points throughout the book.

GB: The balance of the Seer reminds me of the role of the poet more largely in our world. As poet, as writer, where has the book of Comfort ultimately taken you, and what can your readers look forward to?

SH: Comfort contains a lot of the existential concerns and questions I had in my late twenties: should I “settle” into marriage and child-rearing, could I do those things without losing myself in the process, how might I manage all the piles of tasks associated with adulthood and not harm myself in the process? I didn’t consciously connect these themes to my real life at the time, but now I certainly do. I can see how, in delving into the found language of Comfort magazine, I was processing questions of domesticity and partnership as well as my own emotional relationship to labor, which is that I am a workaholic/overdoer by nature.

Well, now I’m (happily!) married and the mom of a toddler, in spite of which I’m much healthier than I was a decade ago with regard to chronic busyness. My work now is to slow down and do less and be fundamentally okay with that. So I really feel like writing Comfort was part of a spiritual movement toward repairing some personal wounds, even though it’s a pretty impersonal book in a lot of ways.

As for what’s next—over the past several years I’ve turned my creative attention homeward, to the place I am from: the Hudson River Valley of New York State. I have a poetry manuscript in progress called “The Hudson Lines,” which documents many years of writing and riding alongside the Hudson River on the Metro-North Railroad. I’m also writing a book of linked essays about landscape and class in the Hudson Valley, which includes topics such as property, wealth, New York City, the river, poverty, accumulation, ruin, scarcity, archives, addiction, apples, beavers, September 11th, Dirty Dancing, whiteness, hoarding, mansions, bungalow colonies, young love, climate crisis, and, actually, the Pacific Ocean.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2023 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2023