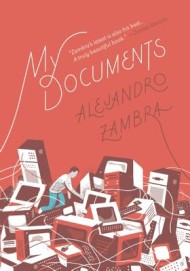

Alejandro Zambra

Alejandro Zambra

Translated by Megan McDowell

McSweeney’s ($15)

by Jeff Alford

Named after the catch-all computer folder, Alejandro Zambra’s My Documents collects an array of meditations on writing and wayward memories of growing up in Chile. To Zambra, an exciting story isn’t as important as the confidence with which it’s told. The short stories in My Documents lean toward the universal: football matches, girlfriends, and hazy sketches of one’s extended family make up most of the action in this collection. The tension here is how to let the elements of a story transcend their sources and evolve into something bigger.

Zambra explicitly toys with this idea in a handful of self-reflective moments. “I was a blank page, and now I am a book” closes “My Documents,” the first story in the collection. Zambra tries to widen the distance from the narrative emptiness of a “blank page” in later stories: “The teachers called us by our number on the list,” opens “National Institute,” but “I say that in apology: I don’t even know my character’s name.” In “I Smoked Very Well,” the narrator is unsure if he is “opening or closing parentheses.” These characters each search for some way to be larger than the story they’re given.

“I Smoked Very Well” is particularly notable; a seemingly autobiographical journal about writing, quitting smoking, and attempting to leave some kind of lasting impression in the world of books. The piece possesses a mundane simplicity but is told with zealous overconfidence that carries Zambra’s prose into something exclamatory, even in its concessions:

I am a person who now doesn’t even know if he’s going to go on writing, because he wrote in order to smoke and now he doesn’t smoke; he read in order to smoke and now he doesn’t smoke. I am a person who no longer creates anything. Who just writes down what happens, as if it would interest someone to know that I’m sleepy, that I’m drunk . . .

The exceptionally bright narrator of “I Smoked Very Well” repeatedly quotes other authors in his digressions, and the narrator (and Zambra, by extension) tries to follow suit and come up with aphorisms of his own: “Cigarettes are the punctuation marks of life,” he proclaims; “What for a smoker is nonfiction, for a non-smoker is fiction.” The act of making these generalizations is more revealing than the actual quips: this is a self-assured author striving to be memorable, knowing that in a world in which all is documented, simply being read is not enough.