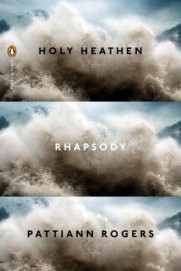

Pattiann Rogers

Pattiann Rogers

Penguin ($20)

by Kimberly Burwick

Two days ago, the word of the day on Dictionary.com was Atticism, meaning concise or elegant diction. Yesterday, it was mirepoix: a flavoring made from diced vegetables, seasonings, herbs, and sometimes meat. Perhaps it is no accident that both words recall the environmentally voltaic poetry of Pattiann Rogers. In Holy Heathen Rhapsody, her latest in over a dozen collections of poetry, the speaker is at once enchantingly sophisticated while maintaining a tenderfoot, almost toddler-like, lens.

Read almost any interview with Rogers and you’ll find she usually mentions childhood. Not always her childhood, but the rich, infantile sensory observations that often encompass one’s early interaction with nature. She says, “Watch young children outdoors. It’s very rare to find a young child who is not enthusiastically curious about the life around him, whatever form that life takes . . . And dandelions, even to my five-year-old grandsons, are amazing and beautiful. And they are right to be so amazed. The life forms on our earth are amazing to children, and they remain amazing for many adults” (Poets & Writers, 2008). In Holy Heathen Rhapsody, Rogers centers this raw excitement within a larger voice of sang-froid. The result: a coolness of observation with an animated, sparkling nucleus.

Constructivist learning theory holds that we construct our knowledge of the world through experience. A child who touches milkweed marks it as soft, fluffy. One watches a seagull steal old chips from a beach and comes to know the bird as the scent of potato and oil, garbage and salt water. Rogers not only recognizes this in theory, she uses it as substratum in her poems. In “Summer’s Company” she writes, “The sun is a total green of light / inside a single mimosa seed riding / inside the sky-green and river- / green of its buoyant pod canoe [see how the green fronds / of the rain unfurl, spooling away / in the ocean’s current.” In syntax and image, such active watching is indicative of both the governable world of childhood, malleable in its raw essence, and the calmer more scientific world of adulthood.

Though Holy Heathen Rhapsody rests upon the idea of a child’s “image-mapping” on the natural world, it also shares the pivotal view of Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods (2008). He argues that allowing children to be fully immersed in nature “has to do with knowing that the earth below us and the sky above us has meaning and we have a place within that meaning.” Rogers is so keenly in sync with this paradigm that diction itself becomes a rich re-immersion in the environment. In her poem “Co-Evolution: Seduction,” we are quickly mesmerized by “Summer, everyday, the flurry-hover / of feeding hermit hummingbirds / and clear-wing moths, bee-pause / and butterfly-flutter on shaking petals.” Spellbound by alliteration and word choice, one not only visualizes but feels the toddler-like sensations of thrilling “flutter-hover” and theatrical “bee-pause.” The tension builds. Later in the poem, “bumblebees with magic keys are everywhere / opening snapdragons with magic locks.” Here, what Rogers engineers with diction plunges into internal rhyme. The effect is pure, unadulterated merriment—nature without retrograde or political rhetoric, but rather with bloom and glare.

Beyond diction and sound, there is yet another way that Rogers uses the child-like voice to assuage responsibility with coy animation. In “Courting With Finesse, My Double Orange Poppy,” she begins, “I know I said I loved you / but I was drunk at the time /on citrus ice and marmalade.” A classic child’s rebuttal, the phrase nearly functions as litotes, as it is an affirmation of the love of one’s flora by way of the negative connotation of drunkenness. Formally speaking, Rogers further fuses informal ode with dramatic monologue. In the fourth stanza of the poem she admits, “And perhaps I did sing to you / of unfolding fringed petals / delicately crumpled first in the bud / but it was really the unwinding / orange nub of the early moon / that I described with some rapture.” Thus, the resulting voice is embossed with playful glorification while also bearing the stamp of a seasoned observer.

Rogers clearly knows a child’s marking of the natural world may not be veridical. Still, she’s not only interested in the facts of the bucolic, not only “the moon” but the associated leaps of the “paralyzed swallow of its toothless / mouth.” Such jumps are not only important for their connotative mastery, but for their halting ability to bring us back to the astonishment of childhood, “and into the deeps, / goosegrass, witchgrass, panic / grass crowfoot grass and nutgrass.”