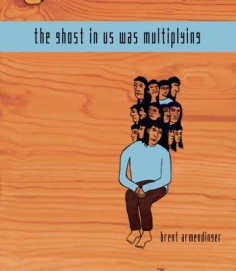

Brent Armendinger

Brent Armendinger

Noemi Press ($15)

by J.G. McClure

At a recent reading in Los Angeles, Brent Armendinger spoke of fragmentation as a way of saying the unsayable. We know all too well that language often fails us when we need it most; it can’t contain our deepest emotions. Rather than ignoring or avoiding the problems of language, Armendinger’s debut full-length collection The Ghost In Us Was Multiplying foregrounds them: such vexed language—fragmented, faltering, insufficient, and all we have—becomes the way in which the poet accesses the inaccessible.

“The Frequencies” shows Armendinger’s many strengths. The poem begins in a fairly stable mode:

Sometimes I think I’m a tree,

the utility pole that history made of that yellow

pine shipped west from the mills of Mississippi,

sheathed entirely in staples.

The metaphor is odd, but intelligible: the self, like the utility pole, is shaped by history and commerce; it is also marked by staples, the remnants of the accumulated actions of others. As the poem continues, though, the metaphor begins to break down:

Run your fingers up and down

my little goalposts, those almost squares

that cover me, anomaly

as true as foliage.

Suddenly the mode has shifted: an implicit you emerges, and the sensual request suggests that maybe this isn’t a poem about the making of the self so much as a poem about love or desire for another. At the same time, the metaphor starts to get mixed: the staples are goalposts—but not quite, they’re much too small for that. They’re squares—or rather, almost-squares. They’re foliage—or rather, they’re “as true as foliage,” but how “true” is foliage in this context, since we’re not talking about a tree but a utility pole, long dead and incapable of producing it? The metaphor is failing, which is not to say the poet is failing. The failure of the metaphor is crucial for the success of the poem, which continues:

for the eighth anniversary

of the war or for the boy

who was shot in the back

when he tried to run away

from the police.He was alive and he didn’t pay his fare and he ran and he was only 19 and No.

We see now why the metaphor must fail. What use is metaphor in the face of our culture’s omnipresent violence—our ongoing wars, our police brutality? For that matter, what good is poetry? The speaker tries to state the facts as clearly as possible, in a very long line that feels too urgent to be broken into verses. But that approach, too, fails: the speaker cuts himself off with the simple, heartbreaking No. “No” seems the only possible response to such senseless violence, and yet it can do nothing for the boy. The poem continues in broken sentences:

The police say –

there is no say entirely.

He was running before he even

got on the bus. 10 times in the back.

10 times running. Entirely.In the late 15th Century

the word for victim fell into

someone’s mouth. And he had and has

and they a name. The police say their guns

can’t fire a shot like the one that No.

They say it was he it was the boy who.

“The police say”—but the speaker understands that it doesn’t really matter what they say. The speaker turns to etymology, looking to the history of the word “victim” to make some sense of this tragedy. Yet he immediately recognizes the failure of that project: to call someone a “victim” merely obscures the fact that “he had and has and they a name.” The speaker then turns back to the present, back to the police, who say that “their guns / can’t fire a shot like the one that” and who insist that “it was he it was the boy who”—but again, the only possible response is No.

The speaker then looks further into language, its histories and failures, before arriving at the final stanza:

What does it matter

the size of the caliber

after ten times kills anything

remotely resembling a him

or a them. A who. Caliber.

The internal diameter

of a name fell into

someone’s mouth. Gone.

Ten times gone. The weight

of all those wires above

and the voices stuck inside them

and when are they going to fall.

Reaching the last stanza, we have to reconsider how the metaphors have been used. They have not merely broken down. Rather, they have been broken apart so that they can be recombined in this chilling whirl. Language is “stuck inside” the wires the speaker-as-utility-pole helps support. He understands that he is implicated in all this violence and that soon—though we cannot know when—the wires and all the voices they hold must collapse.

Throughout The Ghost in Us Was Multiplying, Armendinger remains intensely aware of the troubled relationship between language and suffering. His poem “Diagnosis” is a haunting look at confronting disease. The poem begins:

What a hidden memory is electricity,

lonely as an unflipped switch,

fetal as hope inside a camera.

In the dream a doctor

scrawls the syndrome,

erasing vowels

from our ventricles.

We pull the staple

from his tally like a splinter,

scrambling his

illegible handwriting

into oxygen.

Though the title announces that the poem will be about illness, this lovely and dizzying barrage of opening images leaves us unmoored. We struggle to figure out the relationship between memory, electricity, and the fetal hope of the camera. Likewise, we struggle to figure out what is “real” here—is the diagnosis merely a dream? Or (as the poem will later suggest), is the dream a response to a real diagnosis? This confusion is an invitation to empathy: we feel a bewilderment like the bewilderment of people in the face of bad news. As the poem continues, the dream ends, the medical language becomes more and more dominant, and we understand that the poem is dealing with a literal diagnosis:

Waking breaks the bulb

over our head

with wet eyes and underwear.

We scan our face

for blood and filament,

our impossible birth

precedes us.

How did we get here?

Medicine swerving the molecules

in our body like a clock.

We ferment inside a hush,

ticking like a dance routine.

Though the poem allows us more certainty about its subject here, it simultaneously forces us into a new unmooring. How many characters are there in this poem? What does it mean to speak of “our body,” to combine the singularity of the body with the plurality of the pronoun? At this moment, the poem reaches its chilling final stanza:

Oh Hester, they cut letters

out of our dresses now

before they sew the final A –

they pin the missing shape to our skins

until our skins remember

who’s missing. Grafting

teaches an orchard to pretend –

heavy fruit only

makes it seem

to bend.

Drawing in an allusion to The Scarlet Letter, the poem continues to resist literal sense-making. Instead, it works to give us the feeling of the feeling, without allowing us to comprehend the situation fully. It shows us suffering, stigma, the sense of weight, the sense that the present is at once like the past and worse. Like the speaker of the poem, we’re thrust into intense emotion and denied even the cold comfort of understanding.

Armendinger is a master at using fragmented language with precise purpose. His poems experiment with language and form—this collection includes a poem delivered in the form of an instant messenger conversation, and a poem placed as a footnote within another poem—but never read as mere avant-garde posturing. Instead, Armendinger again and again finds new ways to use defamiliarized language to access the unsayable.

It’s a rare and wonderful thing to find a poet who can so powerfully, vividly, and gracefully engage with the problems of language and the world. The Ghost In Us Was Multiplying is a vital book: experimental, substantial, fragmented, unified, unsettled, and unsettling, Armendinger’s work is key reading for all those who care about what our broken words can do.