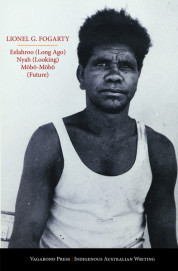

Lionel G. Fogarty

Lionel G. Fogarty

Vagabond Press ($25)

by Robert Wood

Precious little has been written on Lionel Fogarty’s poetic consciousness, or where to situate him in a global literary economy. An indigenous Australian writer, Fogarty is mostly considered alongside Ali Coby Eckermann and Samuel Wagan Watson in a red, yellow, and black identity politics triumvirate—and indeed, one can see in Fogarty’s writing a DuBoisean “double consciousness,” the common walking-in-two-worlds theme. But Eelahroo (Long Ago) Nyah (Looking) Mobo-Mobo (Future) demands a new analysis.

For Fogarty’s latest work, the term “homonymic consciousness” comes to mind. A homonym is one of a group of words that share the same spelling and pronunciation but have different meanings. It is thus about unity and multiplicity at once. Fogarty’s latest work shows a remarkable unity of purpose, voice, and outlook: it is not sameness, however, because there is thrilling multiplicity in his formal invention, from acrostic (“A-U-S-T-R-A-L-I-A”) to long narrative (“Thirty Years from 1983”) to numbered statement (“Register Donate”)—not to mention a multiplicity of emotion (from anger to admonishment to regret).

What results from reading homonymity into this work is the recognition of Fogarty’s distinct poetic idiom, which allows readers to reconsider indigenous sovereignty and power in a contested and occupied Australia. However, to label indigenous poetry simply as a poetry of protest undermines the work’s capriciousness and diversity. In Eelahroo (Long Ago) Nyah (Looking) Mobo-Mobo (Future), we get a complicated, dense, moving portrait of life in all its forms. The reader is challenged, opened up, and eventually lulled by this book. Moreover, we cannot separate out resistance from utopia; there is not only protest here, but also the evocation of a created world. It is this combination that makes Fogarty so compelling.

In his Sydney Review of Books essay on “The Poet Tasters,” Ben Etherington noted the prevailing whiteness of poetry and its reviewers in Australia. Fogarty not only stands out for his appreciable non-whiteness, but also because his poetry works to defamiliarize “the poetry community” from its linguistic surroundings. Few other poets can say they have a brother who died at police hands, and that othered experience comes through in his language. Perhaps Fogarty’s true poetic antecedents can be found in anthropological journals, colonists’ diaries, and explorers’ letters; in these sources we can read transcriptions of songs and myths told in indigenous voices but which deny an authorial identity. The emphasis on repetition common to many song poems comes through in poems like “Maps Gods To Whose,” “Country’s Sub’s No Suss Towns,” and “Olive Pink Fly Over Sums.”

There is also a root in ongoing oral traditions and an international context of which Fogarty is a part, which might account for why Fogarty writes how he does as well as for where we place him. Indeed, the reader will very much recognize the spoken voice in this book. Consider for example the lead poem “Murgon Brawl Cherbourg Brawls,” which begins, “They out there, not hidden / Have you heard of that brawl?” We can see a casual ordinary speech combined with direct address and line breaks, which, when taken together demand the reader to pause and reflect—is the poet speaking of us, asking of us, are we in the space of Poetry or a casual, passing conversation? The language might be ordinary but the rhythm is not. It reminds us, in its use of the vernacular, of some Caribbean writers (Mervyn Morris for instance), Black British writers like Linton Kwesi Johnson for its content, and some Americans, primarily Amiri Baraka, for its intensity. Recasting Fogarty in such a transnational Black milieu forces us to think through the nodes of association, the networks of relation, and the politics of criticism.

When reading Eelahroo (Long Ago) Nyah (Looking) Mobo-Mobo (Future), one will recognize the linguistic dexterity, unique sound shape, unity of purpose, and multiple meaning of words. For readers unaccustomed to his work, it is a good place to begin. For readers expecting more of the same, it is striking for its cohesiveness and power, which only grows with the volume. We must read Fogarty in light of traditions not immediately considered poetic, as well as in contexts that account for more than Australia. It is exciting to think of Fogarty as a starting point for many to experience the vast diversity of Australian literature.