Greg Pape

Greg Pape

Lynx House Press ($15.95)

by Warren Woessner

Four Swans, Pape’s tenth collection of poetry, should come with a map. Apart from an excursion east to bury his mother’s ashes, his poems are firmly rooted in the landscape of western Montana. While the poems in Four Swans are arranged in four sections, and the thread of his mother’s life and last illness is a theme, it is the imagery of rivers and streams—moving, unstoppable water—that connects these poems. In “The Spell Of The Bitteroot,” despite being “ditched and diked, / riprapped and rerouted, / dredged and diverted,” the river remains:

a mouth that won’t stay closed,

a network of living vessels, veins

in a watery leaf of earth,

channels, braids, a continuous flow

of wild water.

While parts of Four Swans recall Jared Diamond’s ecological accounting of the same beautiful, fragile and threatened landscape in Guns, Germs and Steel, Pape seldom slips into political polemic—there is just too much going on. In “What You Should Know To Be A Poet,” Gary Snyder suggests: “All you can about animals as persons. / the names of trees and flowers and weeds. / names of stars, and the movements of planets / and the moon.” In these poems, Pape proves that he has all these bases covered, and his knowledge often spills out in over-exuberant lists, as in “Tracks & Traces:”

I go on walking, glancing down to see the path,

then up into the trees to see the trees, owls

maybe, great-horned, long-eared, sawhet,

woodpeckers, hairy, downy, pileated,

the brown creeper, the snipe, or porcupines, . . .

But Pape is not just a “lister;” he knows how to observe nature; how to look closely. In “Bitteroot Suite,” he sees:

. . . three duck feathers

light and downy, curved upward and held

against stones like boats run aground

in green algae shallows.

No one will ever have to ask Pape about the forebears that influence his poetry; he wears them on this sleeve and inserts stanzas and entire poems from the great Japanese and Chinese masters into his poems. While poets like Shinkichi Takahashi, Tu Fu and Bashō are famed for their evocative simplicity; Pape uses their poems as starting points for both explication and to inspire internal exploration. The longest poem in Four Swans is an homage to the T’ang master, Su Tung-P’o. Pape feels that he is “a friend across time:”

His dream of the Taoist immortal disguised as a black-and-white crane flying

above the river is my dream. His pleasure in words—finding them, arranging

them in clear sentences, satisfying lines—is my pleasure.

Pape knows that he is fortunate to live in a country of “Mountains and Rivers Without End,” a country “shot through with clear light, / a clear light that makes men joyful” as Hsieh Ling-Yun wrote. “Ice Fishing in a Snowstorm” begins with a poem by Liu Tsung-yuan about an “old man . . . fishing alone in the cold river snow” which leads Pape to consider the poetic process:

Ice in an old hole

will dull or break the blades of the auger.

You have to cut a new hole.

You have to sit in the snow and wait.

In the same poem, Pape acknowledges Richard Hugo as one of his influences, and when the poet goes into town, Hugo’s rough affection for the bars, truck stops, and cafés of the West is well preserved, as in “Lunch in Lima:”

All along the bar

the citizens bow before their beers or coffees

and give thanks to Social Security, while the poker

machine in the corner goes ping and pays out

another hand with a one-eyed Jack and a pair

of fives.

In the long prose poem, “Driving Through,” Pape passes a weather-worn hitchhiker while musing on a Basho haiku, stops at “the only light in thirty miles” and realizes that he is in his own Zen riddle:

I started to feel like a sewer rat on my way to another meeting with my colleagues to vote on someone’s fate. I turned around right there and went back for Basho, for Chief Looking Glass, for the one walking through Lolo.

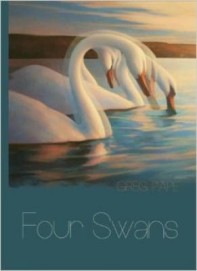

In the title poem, Pape names the four wild swans “Grace. Peace. Dignity. X.” He leaves it up to the reader to decide what X equals.