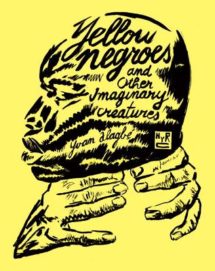

Yvan Alagbé

Yvan Alagbé

New York Review Comics ($29.95)

by Spencer Dew

How to speak of courage or cowardice in the context of colonialism? Are these part of what Fanon dismissed as “white values,” part of the broader epistemological and ethical toolkit settlers hauled from the metropole and used to bash in the minds of those they conquered? Yvan Alagbé, a legend in French comics, addresses such a question in this stunning collection from the New York Review’s comics publishing imprint. This volume represents a contribution to that publisher’s larger goal of providing English language translations of important international works, and Yellow Negroes is explicitly international—international with a “double consciousness” emerging from its black soul.

Blackness—as racialized identity and inherited culture but also an aesthetic mode, an imagining of what scholar Ashon Crawley calls the irreducible otherwise possibility of Blackness as a way of being—shapes the stories here. Visually, the blackness of the lines dominates as well. Alagbé works in lines reminiscent at times of Zen calligraphy, brushwork at once skilled and automatic in the sense of channeled, spontaneous. At other points, the lines resemble gouges, as if, rather than putting ink on a page, the artist were scarifying his subject, imparting a physical trauma to his readers. When one protagonist, having jumped a metro turnstile, is chased down over several agonizing, freeze-frame panels (one cannot but be reminded of the final scenes of Childish Gambino’s “This is America”) and is finally tackled and apprehended by police, the gaze pans out such that the gathered crowd dissolves into blackness, a stain, then a mass of humanity so thick it takes on the appearance of the bars—which, in the final frame of this sequence, with our protagonist in jail, are not merely metal and shadow but also an immaterial and therefore inescapable force, blotting out any idea of freedom, caging this man inside his own doomed fate.

This protagonist, Alain, is undocumented, which is to say the Age of Discovery did not merely mark him with a racialized and thus stigmatized identity, but the Age of Globalism, following on the heels of capitalism’s rampant success with sugar and cotton plantations, furthered marked him as from an unenviable postcode and lacking the golden tickets of those who feel closest to an actual chance of freedom. Lack of documentation is to the contemporary world what legal classification as subhuman was in the past. Alain is no slave—he has a job, or at least had one just before this story begins; he can exercise the supposed free will required to fall in love, rescue a likely unrepairable television unit from the trash, accept an offer of cheese and eggs from another man’s fridge—but he is not a full person under French law. He is trapped in that liminal status of “migrant,” here but not here. I assume his fate, upon arrest, will be deportation, but perhaps that is because I live in America, where the tenuousness of undocumented migrants is such that, indeed, a crime so petty as hopping a turnstile can land one in an open-aired detention camp, then dumped in a country no longer—if ever—one’s own.

America figures in this book, too, of course. Trump’s face makes an appearance in the final, most brutal, story, where Alagbé connects the paving stones by the Seine to a 1961 massacre of Algerians and to a 2017 protest, by a contemporary artist, in favor of migrants seeking refuge in France. “Stones where no distinction can be made” are stones carefully considered by Alagbé, who adds paving stones to the foreground (and a conquistador’s ship in the background) to a devastating one-page inside the front cover: that drowned Syrian toddler, that refugee eternally denied refuge, that image that rose to the status of meme, briefly, and then got drowned in the latest controversy or fad. A dead boy—yet Alagbé, putting those paving stones between us, the viewer, and him, the corpse, seems to say: Look, this is the beach beneath the concrete. A beach of immense human suffering.

Where is the courage or the cowardice in that image, in the original photograph of the dead boy? Do we (with our documentation) applaud the supposed bravery of those who attempt the trek from hell to a better world? Do we castigate ourselves for failing to act, for failing even to imagine an effective path for action? Alagbé, as should already have been established, has no use for cheap sentiment. His characters struggle, they love, they find themselves inadequate vessels for the expression of the agony they bear. In the book’s third story, “Dyaa,” one of the characters from “Yellow Negroes,” Martine, thinks on her husband, who has gone back to Africa, even as she meets and has sex with a cabdriver and fellow migrant, Ibrahima, who thinks of his wife, still back there. “How to tell you that nothing is okay here?” he thinks. Europe, he tells his wife in an imagined letter, is death. “Don’t you come. The water here makes you sick, the air you breathe makes you sick, the cold kills you bit by bit. You’ll have to bring up our child by yourself. The women here do that.” Cowardice or courage? “There is money everywhere here,” he admits, “Just like the lights that shine all night long. But you have to gather it, and that takes time, so much time.”

Alagbé employs, for certain emotional moments, various forms of abstraction, often with African motifs—shapes like power objects hovering above a character’s head, for instance, as when Alain, in “Yellow Negroes,” “dreams of broad-hipped women,” his erect penis rising before him, and an image like a fertility amulet, emerges from those dreams. But the more common abstraction is achieved through a reduction of lines—a pair of lovers becoming so many agitated brushstrokes, bulges, and splayed arrays; Martine, kneeling in a prayer for death, becomes a curve and a tuck, bold black lines converging. The first story here, entirely wordless, is a series of images that slowly come into focus as a naked white woman with a black infant suckling at her breast. Serving as something like a preface to the book, it offers a glimpse of peace, even bliss, that is then followed by page upon page of nightmare.

The other central character in “Yellow Negroes”—antagonist seems too strong a word—is Mario, himself a policeman, as he is proud of noting, an example of what he might describe as the colonized made good, what might also be called a collaborator. Here the issue of cowardice—of “yellow”—comes to a boil. He played an active role in that massacre of Algerians in 1961. His cross, now, is a terrible loneliness, though he also suffers from the cold characters here attribute to Europe but that reflects, more precisely, their place in it. He has a badge, a taste for Gauloises and white prostitutes, but he is impotent and desperate, his powerlessness and need manifest in his performance with all three, whether flashing his identification at a racist landlord, or insisting that his Parisian tastes are superior to those of Africa, or, literally, when he fails to perform after paying a prostitute and then begs for a refund. The single frame of her laughter—her condescension, her pitiless revile for this pitiful man—is one of the book’s many disturbing moments. Of the whorehouse carpet, Mario observes “a tragic feeling amid the vestiges of the past, like yesterday’s dirty dishes,” but this is a description, too, of him, of his life, of the native agent serving the colonial state. If migration offers a kind of double consciousness, so too it opens the possibility for a double culpability, an abandonment not only of the lauded, supposedly universal “white values” of French ideals but also a stark and bloody betrayal of his own people—his sons, as Mario insists of Alain in a scene where loneliness tilts to madness.

In such a situation, is life itself an act of courage or merely the cowardice of postponing suicide? Is love an act of bravery—the persistence of human dignity—or is it more like the mindless need of the addict, an opiate, a way to defer pain? Alain’s white girlfriend points out, in one scene, that if they married, he could get paperwork, documentation, legal status. He dismisses the idea, insisting that one should not get married for ulterior motives. But isn’t it a lifeline, similar to a rescue boat, or groceries taken for free? Alagbé nudges us, in this book, to question the value—not the application, but the value—of documentation. The difference between buying a ticket for the metro and vaulting over the turnstile is more than a legal distinction. There are multiple desires, and angles to desires, at play in the circumstances of every character here—even one I have not mentioned, who stuffs a suitcase full of grilled fish, agouti, and monkey nuts so as to bring a palpable taste of home to this new world of Europe. Alagbé observes, in his final story, this recent trend: “all the talk of ‘migrants,’ or in other words ever since people started fleeing and dying in such numbers and washing up in such numbers on beaches.” Yellow Negroes takes us beneath the beaches to which migrants flee, down to the concrete of their irreducible, multivalent (which is to say messy, sometimes ugly, sometimes euphoric) lives. It is an extraordinarily gripping book, an urgent mirror through which to examine our moment—in its terror and violence, to be sure, but also in the otherwise possibility produced by such shadows.