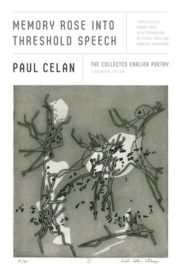

Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech

Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech

The Collected Earlier Poetry

Paul Celan

translated by Pierre Joris

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ($45)

Microliths They Are, Little Stones

Posthumous Prose

Paul Celan

translated by Pierre Joris

Contra Mundum Press ($26)

by John Bradley

These two volumes, a bilingual (German and English) translation of Celan’s early poetry and a translation of much of his prose, offer a tribute to an author that many, including translator Pierre Joris, consider “the major German language poet of the period after 1945.” Memory Rose into Threshold Speech completes Joris’s translation of Celan’s poetry, accompanying his Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014), a major literary accomplishment.

Celan was born Paul Anchel in Czernowitz (now Chernivtsi, in Ukraine) in 1920. His parents were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust, a personal as well as historic tragedy that lurks behind much of Celan’s poetry. In 1947, he changed the Romanian spelling of his last name into Celan. After dealing with “psychic turmoil,” as Joris puts it, Celan died in 1970 by jumping into the Seine.

Reading Celan’s earlier poetry offers a chance to study his evolution as a poet. This statement from Microliths They Are, Little Stones offers a key to that development: “Not the measured verse, but the unmeasured, where the lyrical and the tragical meet and cut across each other, is what makes a poem a poem.” Looking at the three books of Celan’s gathered in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech (Poppy and Memory, Threshold to Threshold, and Speechgrille), the reader can easily see that Celan began by writing poetry that put more emphasis on the lyrical and then gradually converted to put more emphasis on the “tragical.” The very first poem in this collection, “A Song in the Desert,” shows just how caught up in the lyrical and romantic Celan was: “I pulled my black stallion around and jabbed at death with my rapier.” In another early poem, entitled “For Naught You Draw Hearts,” he begins: “The Duke of Stillness / recruits soldiers in the castle courtyard.” But even in these more lyrical poems, the surreal can be found, as the next line in this poem attests: “He hoists his banner in the tree—a leaf that blues for him when it autumns.” That use of “blues” and “autumns” as verbs shows the future path Celan would follow, bending language in new ways.

Reading Celan’s earlier poetry offers a chance to study his evolution as a poet. This statement from Microliths They Are, Little Stones offers a key to that development: “Not the measured verse, but the unmeasured, where the lyrical and the tragical meet and cut across each other, is what makes a poem a poem.” Looking at the three books of Celan’s gathered in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech (Poppy and Memory, Threshold to Threshold, and Speechgrille), the reader can easily see that Celan began by writing poetry that put more emphasis on the lyrical and then gradually converted to put more emphasis on the “tragical.” The very first poem in this collection, “A Song in the Desert,” shows just how caught up in the lyrical and romantic Celan was: “I pulled my black stallion around and jabbed at death with my rapier.” In another early poem, entitled “For Naught You Draw Hearts,” he begins: “The Duke of Stillness / recruits soldiers in the castle courtyard.” But even in these more lyrical poems, the surreal can be found, as the next line in this poem attests: “He hoists his banner in the tree—a leaf that blues for him when it autumns.” That use of “blues” and “autumns” as verbs shows the future path Celan would follow, bending language in new ways.

Perhaps the most famous of Celan’s early poems is “Deathfugue,” which was first published in Bucharest, May 2, 1947, under the title “Death tango.” Already Celan had found his voice and style, blending and balancing the lyrical and tragical, as can be seen right from the opening lines:

Black milk of morning we drink you evenings

we drink you at noon and mornings we drink you at night

we drink and we drink

we dig a grave in the air there on lies at ease

A man lives in the house he plays with the snakes he writes

he writes when it darkens to Deutschland your golden hair Margarete

he writes and steps in front of his house and the stars glisten and he

whistles his dogs to come home

he whistles his jews to appear let a grave be dug in the earth

he commands us play up for the dance (43)

This hypnotic mix of surreal language and repetition creates a deep emotional resonance.

Some readers, however, including a major German critic, denied that the poem related to any historical event, such as the Holocaust, considering “Deathfugue” instead “a gorgeous dreamlike surrealist fantasy with no reference to the actual world.” This denial of his evoking the historical led Celan to a more austere style in his next book, Threshold to Threshold, a style that would employ more of the tragical, as can be seen in “By Twos”:

The dead swim by twos,

by twos, girdled by wine.

In this girdle of wine,

the dead, they swim by twos.They braided their hair into mats,

they live toward each other.

You, throw once more your die

And dive into the two’s eye.

It’s hard not to think of Celan’s dead parents when reading this poem, and hard also not to think of Celan’s dive into the Seine.

Another aspect of this more austere style is Celan’s use of compound-word neologisms. These compound words, which German seems particularly suited to, add a complexity and at the same time a specificity for Celan, a way both to expand the possibilities of language and to narrow his focus, as in the opening stanza of “Windtrue”:

Tablewall, gray, with nightfrieze.

Fields, windtrue, square after square

empty of writing.

Lightipede climbs past.

The compound words here allow for a more intense description of the scene, culminating in “lightipede,” which suggests a kind of centipede, its legs bristling with light, one of his most unusual—and nightmarish—neologisms.

Celan’s distinctive use of language, though, wasn’t merely a stylistic discovery. Rather, it gives the sense of a writer trying to create a new poetic after the Holocaust. Often that struggle with language culminates in a kind of prayer, such as in “Psalm,” from NoOnesRose:

NoOne kneads us again of earth and clay,

no One conjures our dust.

Noone.

Praised be thou, NoOne.

For your sake we

want to flower.

Toward

you.A Nothing

we were, we are, we will

remain, flowering:

the Nothing-, the

NoOnesRose. (263 & 265)

These three stanzas of “Psalm” illustrate the tension between an intimate address to a higher power and a deep skepticism that this entity exists. Joris’s translation brilliantly captures this tension right from the opening line, with “kneads” evoking the word “needs.”

Joris has not only masterfully translated Paul Celan’s poetry, but also his prose in Microliths They Are, Little Stones. While this volume is not a complete collection of all of Celan’s prose, at 294 pages it certainly gives the reader a full-sized window into the mind of Celan. This window begins with the title of the book, which comes from the following entry:

Microliths they are, little stones, barely perceptible, tiny xenocrysts inside the thick tuff of your existence—and now you try, word-poor and perhaps already irrevocably condemned to silence, to read them together into crystals? You seem to wait for reinforcements—say, where should these come from?

This collection of prose writings do indeed feel like “little stones,” consisting of aphorisms, quotations from readings, short narratives, notes for a conference presentation, and drafts of letters. Celan was a skilled aphorist, much like his surrealist predecessor Franz Kafka: “Teach the fish the language of fishing hooks”; “He who really learns how to see, closes in on the invisible”; “Another name for love: patience.” These writings are not frivolous, however. One letter written by Celan offers this painful disclosure: “the hand that will open my book has perhaps shaken the hand of the one who murdered my mother.” The past never loosened its grip on Celan.

This collection of prose writings do indeed feel like “little stones,” consisting of aphorisms, quotations from readings, short narratives, notes for a conference presentation, and drafts of letters. Celan was a skilled aphorist, much like his surrealist predecessor Franz Kafka: “Teach the fish the language of fishing hooks”; “He who really learns how to see, closes in on the invisible”; “Another name for love: patience.” These writings are not frivolous, however. One letter written by Celan offers this painful disclosure: “the hand that will open my book has perhaps shaken the hand of the one who murdered my mother.” The past never loosened its grip on Celan.

While Microliths offers some general insight into Celan, this prose volume will be of interest mainly to the Celan scholar. The section entitled “Texts on the Goll Affair,” for example, helps the reader to better understand an event that deeply scarred the author. The German poet Yvan Goll died in 1950, and shortly after that his widow, Claire, accused Celan of plagiarizing her husband’s work. Though this was completely untrue, she persisted in her claims, even creating false documents to support her charges. Particularly hurtful was her claim that Celan’s parents were not actually murdered by Nazis. In a letter about Claire Goll’s charges, Celan writes: “For this whole matter is in no way a literary affair, it is only [Celan’s italics] infamy.” Claire Goll unleashed such trauma in Celan that her false charges were, according to Joris, “one of the triggers of his suicide.”

With the translation of all of Celan’s poetry completed, as well as most of his prose, Pierre Joris notes that this concludes his “fifty-year involvement with translating Paul Celan.” It is quite an accomplishment. The care Joris has taken in translating Celan can be found in the notes, entitled “Commentary,” for Memory Rose into Threshold Speech. In the 153 pages of notes, the reader will find information on when and where a poem was composed, who it may have been written for, previous versions of a poem’s title, pertinent excerpts from Celan’s letters, references to other poems by Celan, as well as allusions to other poets, and references to various myths. There’s even a diagram for one poem, “Shroud,” to illustrate “the dense web of words in this poem.” It’s no wonder that Joris’s translations of Celan seem to radiate clarity while preserving Celan’s complexity.

This complexity relates to a comment by Celan on why he wrote in German—he felt he had to “cleanse his mother’s high-German of all the poison injected into it by her murderers’ ideology.” To purify a language of its history, of its misuse by the speakers of that language, Celan’s poems—to quote from his poem “Speak, You Too”—“grow thinner, more unrecognizable, finer!” The poem concludes:

Finer: a thread

along which it wants to alight, the star:

so as to swim further down, down

where it sees itself gleam: in the swell

of wandering words.

Celan must take us down deep into the roots of language in order for it to shine. His poetry, thanks to Pierre Joris, will continue to shine for English-speaking readers amidst “the swell / of wandering words.”