Thomas R. Smith

Thomas R. Smith

White Pine Press ($16)

by Allan Cooper

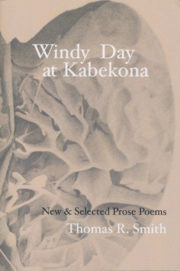

For the last four decades, Wisconsin poet Thomas R. Smith has been quietly writing some of the finest prose poems of his generation. Readers will find them scattered through most of his seven major collections, from Keeping the Star (New Rivers Press, 1988) to The Glory (Red Dragonfly Press, 2015). This new collection, Windy Day at Kabekona, is a gathering of riches from those books, coupled with a generous offering of new prose poems written in the past few years.

A number of these prose poems are rooted in the heritage of Smith’s midwestern world: one fine example is “Portrait of my German Grandparents, 1952.” Here, Smith doesn’t rely on simple description, although he is a master of it. He presents a grandfather in old age, a man who “hardly knows this world anymore, and will not know the world it is becoming, just as the grandchildren, grown up, will not be known.” In a few words, Smith captures the passage of time and the changing world, where old ways are disappearing and fear and uncertainty are taking their place. The final effect is deeply convincing.

There are wonderful poems in this collection about the natural world, poems about sparrows, moles, river otters, ants, and wasps. Smith discovers connections between the human and natural world that are both startling and moving. In a poem about finding a dead raccoon on a morning walk, he urges us to observe more closely and to think more profoundly about those daily occurrences we so often overlook:

Pass by in your haste, and ignore it. Or notice the coarse-furred limbs extended, reaching for some withheld deliverance. Think of the new streets and homes, the people who no longer know where they are. Notice how closely the hands resemble your own.

In “Your Inner Face,” Smith says that we have two faces: the one “others see, in restaurants and banks,” and another, “so true to its desires, unbelievably beautiful.” In a Rumi-like way, Smith suggests that if we could see everyone’s inner face at once, it would create a kind of heaven. I would add that when Smith looks at an object closely, he finds an inner connection between himself and the object, creating another kind of heaven. At a time when there are huge chasms between people, and the rhetoric of “fake news” permeates our days, Smith offers us alternatives which are both nourishing and healing.

Many lovers of poetry will be familiar with the masters of the contemporary American prose poem, among them Robert Bly, James Wright, Mary Oliver, and Louis Jenkins. With Windy Day at Kabekona, Smith takes his rightful place among them.