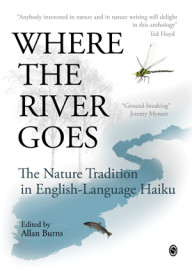

The Nature Tradition in English-Language Haiku

The Nature Tradition in English-Language Haiku

edited by Allan Burns

Snapshot Press ($45)

by Peter McDonald

Casual readers and practitioners in English-language haiku often assume this brief poetic form, imported to the West from Japan at the turn of the 19th century, is indelibly associated with elegiac snapshots of nature in three-line poems of 5-7-5 syllables. They might also have heard of the great master haikuist Matsuo Bashō, who elevated haiku to an art form in the 17th century. It was Bashō who stressed quiet attention to the immediacy of an image taken from seasonal nature, where the “haiku moment” must be spontaneous, shorn of adornment or simile, with no intrusion of the authorial ego.

Today, of course, in its burgeoning western tradition, haiku has evolved into multiple creative strains, far removed from the lockstep syllable count of its early years and often with only an incidental focus on nature. Indeed, ascendant everywhere—even in Japan—is the senryu form of haiku, where the pratfalls and pangs of humanity form the poetic nucleus. Nature in most senryu is given second billing at best.

In his magnificent new compendium Where the River Goes: The Nature Tradition in English-Language Haiku, editor Allan Burns calls the reader back to haiku’s roots in paeans to the natural world. Readers opening this book will be blessed to step into quietude, inoculated, if only briefly, from the clamor of smartphones and multi-tasking.

the snowy meadow:

a wind-blown feather follows

the tracks of the fox

—Nick Virgilio

This work is an in-depth collection of nature haiku unlike any in the long line of western anthologies dating back to Cor van den Heuvel’s groundbreaking The Haiku Anthology (1974). Van den Heuval set a standard of giving many poets just a poem or two, thereby evenly covering the waterfront of illustrious practitioners. With the refreshing eye of a curator, Burns has chosen an opposite tack, giving fewer poets greater space to reveal more deeply the individual strengths of their craftwork. This survey is thus remarkable in that it gives the reader a chance to peruse each entrant’s work in a manner more like a meditation, as if embarking on a reflective amble through the seasons, where each of the forty poets presented is engaged as guide and companion along the way.

Beside the waterfall . . .

opening with all its blue

the bellflower

—vincent tripi

Burns’ fine introduction, at sixty enlightening pages, along with his postscript notes, references, and index, form that rare exegesis that melds scholarship, environmental issues, Zen practice, and the wider world of lyric poetry with a concise history of haiku’s traditions, placing this short-form poetry forefront in the larger context of western nature writing from Thoreau to Aldo Leopold to contemporary journalists investigating the degradation of whole ecosystems under the threat of climate change. More effective still, and with the same revelatory insights, Burns opens each poet’s section with a luminous mini-essay that expertly interweaves a concise biography of the poet with comments on their unique style, highlighting inventive attributes of their respective work. For any lay reader, or even for a haiku connoisseur, this quiet landmark of a book offers a perfect grounding in the essentials of the haiku moment.