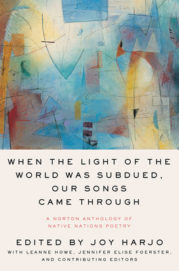

A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry

Edited by Joy Harjo, LeAnne Howe, and Jennifer Elise Foerster

W.W. Norton & Company ($19.95)

by Mike Dillon

In 1890, the year of the Wounded Knee Massacre, the US. Census bureau announced the closing of the U.S. frontier. Manifest Destiny had done its work. The American narrative, which “began in perfection and aspired to progress,” as historian Richard Hofstadter wryly noted, now incorporated the myth of the vanishing race: Native Nations would slip away as unobtrusively as the act of forgetting.

In 1890, the year of the Wounded Knee Massacre, the US. Census bureau announced the closing of the U.S. frontier. Manifest Destiny had done its work. The American narrative, which “began in perfection and aspired to progress,” as historian Richard Hofstadter wryly noted, now incorporated the myth of the vanishing race: Native Nations would slip away as unobtrusively as the act of forgetting.

A brilliant new book edited by U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo and a stellar cast of supporting editors, and containing the work of 161 poets from more than ninety Native Nations, When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry continues the hard labor of dispelling this ingrained myth. Along the way, it necessarily challenges the U.S.’s rose-tinted assumptions about its own history.

Spanning four centuries, the anthology features leading figures in the contemporary American poetic canon, including Louise Erdrich, Gail Tremblay, Sherman Alexie, Simon Ortiz, Natalie Diaz, Layli Long Soldier, and N. Scott Momaday. Simultaneously, the editors have given new life to vivid, mostly-forgotten voices from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and they have spotlighted younger poets clearly destined to assume eminent roles in years to come.

Pulitzer Prize winner Momaday, with the opening lines of the book’s invocation, “A Prayer for Words,” foreshadows the sacramental weaving of past and present found in the poems that follow when he writes, “Here is the wind bending the reeds westward, / The patchwork of morning on gray moraine.” Harjo’s introduction, at times beautifully incantatory, also provides vital context:

Our existence as sentient human beings in the establishment of this country was denied. Our presence is still an afterthought, and fraught with tension, because our continued presence means that the mythic storyline of the founding of this country is inaccurate. The United States is a very young country and has been in existence for only a few hundred years. Indigenous peoples have been here for thousands upon thousands of years and we are still here.

When the Light of the World Was Subdued is divided into five sections: Northeast and Midwest; Plains and Mountains; Pacific Northwest, Alaska, and Pacific Islands; Southwest and West; and Southeast. Each section contains valuable introductions by contributing editors and writers. Readers may also be surprised to find an additional bonus: the inclusion of poets from Hawaii, Guåhan (Guam), and Amerika Sāmoa. Manifest Destiny, after all, didn’t stop at continent’s end, but took to the water.

The Northeast and Midwest section opens with Eleazar (?—1678), tribe unknown, who entered Harvard in 1675 and died of smallpox, likely before graduation. His elegy for one Thomas Thacher, written in Latin, is modeled on classical forms—“I will try to remember and retell, / with sad grief”—bringing in the names of Apollo, Achilles, and Christ along the way. The last poem in that same section, by b: william bearheart, born in 1979, concerns an Andy Warhol painting of Geronimo in a Las Vegas art gallery. Eleazar and bearheart serve as section bookends—a surreal, historical arc somehow achingly American.

In one of the introductions to the Pacific Northwest section, poet Cedar Sigo, born in 1978, writes:

I have come to think of Native Poets as warriors/prophets that can move (almost routinely) beyond our own bodies. We are hovering, scribing entities, free to drop back into our trenches as needed. . . . Becoming a better listener is also such a huge part of becoming a more complete poet, to always leave ourselves open to new frequencies.

One of those frequencies is a magical realism which just might be true, as in “Mind Over Matter,” by Louis Little Coon Oliver (1904-1991): “My old grandmother, Tekapay’cha / stuck an ax into a stump / and diverted a tornado.”

Some of the poems reflect the conventions of 19th century poetry inculcated in white schools, as exemplified in the last stanza from a short poem by William Walker Jr., who died in 1874.

Long have I dwelt within these walls

And pored o’er ancient pages long.

I hate these antiquated halls;

I hate the Grecian poet’s song.

Jennifer Elise Foerster, born just over a century after Walker’s death, reflects his poignant, clear-eyed bitterness when she remembers what her grandmother told her in “Leaving Tulsa”: “When they see open land / they only know to take it.”

Among the eclectic range of poetic styles are masterpieces of satire. In “Sure You Can Ask Me a Personal Question,” Diane Burns (1957-2006) sends up a condescending interlocutor:

Yeah, it was awful what you guys did to us.

It’s real decent of you to apologize.

No, I don’t know where you can get peyote.

No, I don’t know where you can get Navajo rugs real cheap.

No, I didn’t make this. I bought it at Bloomingdales.

There is also a range of tones, as when, in her poem “The Wall,” Anita Endrezze, born in 1952, takes aim at Trump’s wall—“Let it be built / of guacamole so we can have a bigly block party”—before ending on an all-too-recognizable tragic note: “Make it a gallery of graffiti art, / a refuge of tumbleweeds, / a border of stories we already know by heart.”

To read this 458-page Norton anthology at a time when this country’s darkest pathologies walk in broad daylight only intensifies the book’s importance. More than 130 years after the “closing” of the American frontier, these poets have a thing or two to say about our common history. And so these poems come through to us, shining from the mysterious fluid of time.