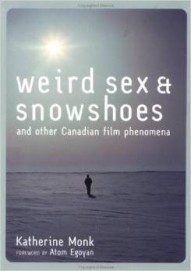

Katherine Monk

Katherine Monk

forward by Atom Egoyan

Raincoast Books ($18.95)

by Brian K. Bergen-Aurand

After only a few titles and a handful of directors, such as David Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, Michael Snow, and Norman Jewison, many filmgoers' cachés concerning Canadian cinema run dry. Thankfully, Katherine Monk's book can alleviate that arid condition. Composed of thematically driven chapters, biographical profiles and filmographies, studies of various Canadian film movements, and reviews of 100 Canadian films, Weird Sex and Snowshoes has the power to increase, exponentially, a reader's knowledge of the subject. The first such excursion into Canadian cinema since Martin Knelman's 1977 This is Where We Came In, Monk's study updates Knelman's popular approach and provides an array of facts and factoids concerning the English and French Canadian filmmaking traditions. Running over much of the same ground as Christopher E. Gittings's Canadian National Cinema (Routledge, 2002), but in a less academic manner, Weird Sex is an interesting primer and valuable catalog for beginning a journey into this cinema today.

Monk, originally from Montreal, is now a Vancouver-based arts journalist who has had brief experiences in low-budget filmmaking. She wrote Weird Sex to inform people about Canadian film and encourage them to engage with it—not to provide an exhaustive survey of all its history and complexity. In that light, the book takes sweeping looks at this national cinema and the "identity crisis" of Canada in order to show viewers how to watch the films, respect them, and eventually love them. Written for the "masses," its hope is to capture the essence of the experience of Canadian cinema by communicating a large amount of critical and cultural study to a popular audience.

Weird Sex is difficult to read straight through, though, due to the sweeping generalizations and cloudy descriptions that surface in the thematically driven chapters. Even after repeated reading, a good deal of this book remains unclear. For example, when summarizing the essential difference between Canadian and Hollywood cinema, Monk writes about the birth of the Canadian Film Board and how its formation under the Scottish documentarist John Grierson's leadership has left a permanent mark on Canadian filmmaking.

In this Scotsman's mind, film was not—in any way, shape or form—supposed to be a vehicle for mindless entertainment aimed at making oodles of box-office cash or building a completely bogus national identity. Therein lies the seminal difference between Canadian and American film: Canada's tradition grew out of an institution and a socialist-minded idea of showing Canadians honest reflections of themselves. The American, or Hollywood, film tradition began as a collective dream in the minds of several Jewish immigrants who were possessed by a desire to create pure fantasy and to reinvent the American Dream as an accessible, if entirely ethereal, ideal.

The binary between United States (Hollywood) and Canadian filmmaking is clear, and Monk holds to this opposition through most of the remainder of the book. What are not so clear, however, are the details of statements such as this one. Has Canadian cinema never been driven by profit? Has Hollywood only ever been? What is the relation between "institutional" and "collective" filmmaking when the word "collective" carries such positive significance in so many other (national) film histories? What is Monk implying by the phrase "Jewish immigrants," and how is their immigration different from that of Grierson? Many such unclear passages remain unresolved throughout the body of this text.

In the end, this book is most valuable in small doses, for its brief discussions of particular films, movements, and filmmakers from different Canadian filmmaking traditions. The reviews at the end serve as nice introductions to 100 Canadian films and provide a solid list for those who might want to learn more about this national cinema from the films themselves.

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Winter 2002/2003 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2002/2003