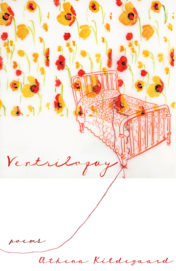

Athena Kildegaard

Athena Kildegaard

Tinderbox Editions ($15)

by Heidi Czerwiec

Ventriloquy unites the expansive outlook of poet Athena Kildegaard with the recent expansion of Minnesota’s Tinderbox Poetry Journal into a new press, Tinderbox Editions. The five sections of this rich collection expand from the garden to saints, divination, and ultimately to the universe. By engaging with the garden and metaphysical concerns, Kildegaard evokes Louise Glück’s The Wild Iris, in which the poet-gardener-speaker also throws her voice. But where Glück’s project, while powerful, feels tightly controlled and more intellectual, Kildegaard’s is more surreally messy—her saints are “Contrary and Futile” and her divinations start and end by pointing to the things of this world.

In the eight-line portraits of the first section, “Garden of Tongues, Garden of Eyes,” Kildegaard’s speaker takes a close look at various flowers, as in “The Clematis”:

Hush, hush, they whisper at dusk

then furl themselves tight as virgins.

The summer nights are too short

for turpitude, but the clematis

take no chance.

“The Saint of Whimsy” snatches at things—“nutcracker with a sky-blue cape and a bear head, / . . . / gingko leaves forceps two piano keys white and black”—and laughs at the collectors who follow her around, while “The Grass Saint” is depressed “because she knew bison / reduced to bar décor.”

The poems of the “Divination” section list various means by which the speaker tries and fails to explain her world. “It’s the sky . . . ceiling of the world,” the speaker of “By Fable” says: “Her throat tickles with failure. The sky / is falling. She’s hoarse as shucked corn.” But while concerned with intrusions of the numinous, this Cassandra’s divinations are linked to the female body’s experiences: the desires and fears of puberty, motherhood, and age. In “By Ice” she holds her dying mother’s hand, tries “to keep her mother tethered/ to this world” by reminding her of

the fur-lined glove her mother

dropped and, the next morning, found,

the sky clear, the glove frozen to gravel.

In the last section, “Still Life with Universe,” ekphrastic prose poems telescope between the micro- and macrocosmic to interrogate the nature of still-lifes themselves—their tension between stasis and story, their illusion of permanence. “Still Life with Passenger Pigeons” asserts “There’s a story here: cracked pepper spilled across the table . . . a galaxy, a startled flock, a Braille riddle.” And the ending of “Still Life with Giorgio Morandi’s Easel” could be a portrait of this entire poetry collection: “A silent arsenal of everyday objects, bristling and flat-bottomed.”