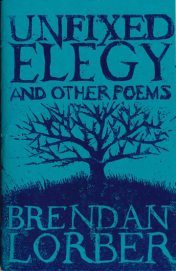

Brendan Lorber

Brendan Lorber

ButterLamb ($7)

by Davy Knittle

In Brendan Lorber’s chapbook Unfixed Elegy and Other Poems, the title poem is full of tense twins. Here is work that experiments with living and dying as they double on themselves from the first lines: “Take shape OK give it back / sweet world or tempest above.”

But what is an “unfixed elegy?” Is it a poem for the unfixed—whether for the unsolved or unrepaired, or for those unseated from life, or from death? Lorber’s work is propelled by an anxiety to shadowbox death, to figure it out, but it also doesn’t want to, and what propels that anxiety remains unclear.

The lines in “Unfixed Elegy” are characterized by wide internal spacing, leaving room for ghosts, or for extra time to double back on what’s just doubled back on itself. The space becomes an encouragement to hang out in the language:

Each year takes the next two to recover

yet this is living Every sexy line

ave maria’d to a new ring around

the rosy I like jokes but most are on me

The nothing that demands a double

Perhaps an unfixed elegy is one that loops, that loses its grounding in death and circles through states of being and its own language. “Unfixed Elegy” thus becomes a lyric contortion, raising up the figures of “sweetness,” of “desire,” and of “hands”—in the tradition of, for instance, “sweetness and light”—and then twisting them, as in “sweets // we reach at the cost of hell and back.”

Forces of all kinds in “Unfixed Elegy” are so intensified that they’re terrible and lovely at once, and repeat forever. Here, “Problems unsolved forever are another problem” and the question is posed: “How can desire be fickle when / all it wants is endless advance through / more desire?”

The death of others creates both desire and problems, where “I don’t want to remember the dead / I want them alive” and yet “your death / is all we need to bring you back.” Lorber takes a number of different stances on managing death and its environs, shifting his position and identifying places where the ability to take a stand on death is itself unfixed.

Other recurring motifs include a set of fragments from “Ring Around the Rosy,” where the sweetness of the song, how light it is about warding off or surrendering to death, echoes the tension between the grave and the sweet against which the chapbook pulls.

In the final three sections of the poem, its circuits resolve into a focus on the “new year,” and its final section, the poem becomes a prayer carrying the weight of both loss and sweetness:

May the element of water not rise up

against us The element of space not

rise up Earth not rise May fire not

Nor air May the sounds lights and rays not

May the infinite oh yeah? be met with yeah!

In the chapbook’s litany of prayers, the final one in this stanza speaks most clearly to a central desire to encounter a response that pulls its cycle forward. If “your death / is all we need to bring you back,” then it is finality that makes possible the doubling of a return, where death is a response. In Unfixed Elegy, ending moves things along.

There’s an inescapable speed to Lorber’s poems; the accurate and sweetly chilling sense that life is passing as one reads, that “each year takes the next two to recover / yet this is living.” “Unfixed Elegy” suggests that the fact of living is more than can be made sense of in each moment, that we’ll never catch up to ourselves, or agree with ourselves, that the dead can come back to us, that time will never add up.

Lorber has created an expert network of tensions here: the finite and the infinite, the fixed and the unfixed, the planet and the body, the dead and the living, the surety of death and the question of the return of those who have died, of being called back and being brought back, of problems and desire, of death accepted and death fought, of wondering and knowing, of clear tensions and webbed ones. Unfixed Elegy and Other Poems is a chapbook where “the shortest distance / between two points are other points with / distance between them.” What an unwinnable set of distances this is, and yet what a hand, offered out and “strong enough to lift / our weight.”