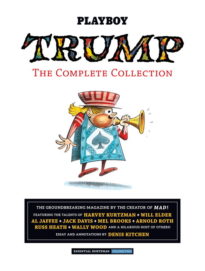

Trump: The Complete Collection

Harvey Kurtzman, et. al.

Dark Horse Books ($29.99)

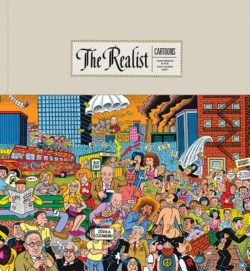

The Realist Cartoons

Edited by Paul Krassner and Ethan Persoff

Fantagraphics Books ($44.99)

by Steve Matuszak

It’s either fitting or ironic that, when America was on the verge of swearing in a president who throughout his campaign had waged a scorched-earth war on truth—his unrepentant lying corrupting the concept of truth more thoroughly than the much-maligned postmodernists had ever done with their opaque, gnomic theory—this past December saw reprints of comics associated with two important twentieth-century American satirists who used humor to shine a sometimes harsh light on reality to get at the truth: the felicitously titled Trump: The Complete Collection, edited and co-written by Harvey Kurtzman, and The Realist Cartoons, which collects cartoons from The Realist, the freethought magazine founded and edited by Paul Krassner.

While Kurtzman and Trump are less well-known to a general audience, both are highly regarded by comics cognoscenti. Kurtzman, who has a prestigious comics industry award named after him, was a trailblazer in the work he did for legendary comics company EC, first with his ironic, anti-war war comics Frontline Combat and Two-Fisted Tales, and then, more famously, for creating Mad in 1952. But his success with Mad was his undoing. Shortly after pressuring publisher William Gaines in 1955 to turn Mad from a comic book into a magazine, he demanded that Gaines give him majority ownership of the magazine. Instead, as is described, surprisingly, in Paul Krassner’s introduction to The Realist Cartoons, Kurtzman was fired, his obscurity cemented as he went on to create a series of relatively unsuccessful satirical magazines until landing in the back pages of Playboy with his comic strip—unfortunately, heavy on the strip—Little Annie Fanny.

While Kurtzman and Trump are less well-known to a general audience, both are highly regarded by comics cognoscenti. Kurtzman, who has a prestigious comics industry award named after him, was a trailblazer in the work he did for legendary comics company EC, first with his ironic, anti-war war comics Frontline Combat and Two-Fisted Tales, and then, more famously, for creating Mad in 1952. But his success with Mad was his undoing. Shortly after pressuring publisher William Gaines in 1955 to turn Mad from a comic book into a magazine, he demanded that Gaines give him majority ownership of the magazine. Instead, as is described, surprisingly, in Paul Krassner’s introduction to The Realist Cartoons, Kurtzman was fired, his obscurity cemented as he went on to create a series of relatively unsuccessful satirical magazines until landing in the back pages of Playboy with his comic strip—unfortunately, heavy on the strip—Little Annie Fanny.

The most spectacular of those failed magazines, and the shortest lived, was Trump. Bankrolled by hotshot young publisher Hugh Hefner, Trump was Kurtzman’s dream come true: not another cut-rate comic book, but a “slick,” a lush, full-color magazine aimed at adults. So Kurtzman brought to Trump some of Mad’s most inspired talent—Al Jaffee, Wally Wood, Arnold Roth, Jack Davis, and his life-long partner-in-crime Will Elder, who worked with Kurtzman on everything from Mad to Little Annie Fanny. As Al Jaffee once reminisced, “Harvey said to the people at Mad, ‘I’m leaving Mad. Who wants to come with me?’ and nearly everybody went with him. He was like the Pied Piper.”

So Trump abounds with dazzling cartooning. But the debut issue’s crowning achievement is “Our Own Epic of Man,” two over-sized, captioned illustrations brimming with detail that depict mid-twentieth century America distorted through the funhouse mirror of how artists a million years in the future might imagine our culture. It is a delightfully inverted parody of Life magazine’s then-popular The Epic of Man series, which purported to put into vividly painted illustrations scientific theories about how humankind lived tens, even hundreds, of thousands of years ago. The Trump illustrations are so epic they spill over the page break, requiring a fold-out that recalls Playboy’s centerfolds, a resemblance Kurtzman could not leave unmentioned, so he includes a quarter-page fragment of an image of an apparently nude woman playing chess, text at the top of the photo proclaiming, “Hey! Wrong foldout! This foldout goes in a different magazine!” Such playful use of form is pure Kurtzman.

It also suggests the almost unruly lengths to which the magazine would go for a joke. Ideas are literally all over the place, filling every nook and cranny, which for some is as exhausting as it might be funny. As Playboy art director Art Paul reported to Hefner in a memo after the first issue of Trump had been released, “I’ve gained new respect for the initial humor of the magazine, but the pacing, layout and typography continue to jar my over eager sensibilities. The magazine has the pacing, type and layout of an explosion . . . All in all it’s a hell of an interesting beginning, but I am out of breath.”

So, in January 1957, after only the second issue, Hefner pulled the plug on Trump. In his introduction, Denis Kitchen reports on plenty of reasons given as to why Hefner had squelched the fledgling magazine: Hefner didn’t think the material in Trump foretold a cultural phenomenon the likes of Playboy or Mad; Bob Preuss, Playboy’s chief financial officer, told Al Jaffee years later that Kurtzman had difficulties meeting deadlines, a problem with serious financial implications for a magazine; and going into its second issue, Trump had already cost Hefner almost $100,000, which it hadn’t been able to make up in sales—as Hefner eventually put it, “I gave Harvey Kurtzman an unlimited budget and he exceeded it.” Worse, this was at a time when Hefner’s credit was over-stretched, causing him to cut costs on all of his enterprises, the upshot of which was, Kurtzman quipped: “Everybody took pay cuts, and I got my throat cut.”

In addition to beautifully reprinting the first two issues of the magazine, Trump: The Complete Collection also includes art and concepts for material that was going to appear in issue three, which promised to be no less dazzling and innovative than its predecessors, including something that appeared to be a cross between a fold-out and a puzzle called a “hexahexaflexagon” (a name that Kurtzman thankfully shortened to the “Flexagon”), “a complex visual puzzle . . . formed by folding strips of paper into nineteen connected equilateral triangles to create a hexagon shape, which when ‘flexed’ can change its surface in an amazing eighteen combinations.” It’s unclear how this puzzle is an example of truth-telling, but it sure looks fun.

One year after the demise of Trump, in the spring of 1958, upstart comedian, journalist, and erstwhile violin prodigy Paul Krassner launched his long-running magazine of “social-political-religious criticism and satire” The Realist. It is telling of Kurtzman’s influence on American satire that the first issue of The Realist was produced in the offices of Mad magazine and was, in fact, born of Mad. Krassner had begun contributing to Mad magazine as early as 1955, shortly after Kurtzman left, but wanted to write more adult material, so he eventually abandoned Mad to create The Realist. His magazine’s first subscriber was comedian and TV personality Steve Allen, who sent gift subscriptions to others, including Lenny Bruce, who himself sent out more gift subscriptions. “From this momentum,” Krassner wrote in his memoir Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut, “the satirical wing of my readership would grow,” as would the influence of both Krassner and The Realist.

One year after the demise of Trump, in the spring of 1958, upstart comedian, journalist, and erstwhile violin prodigy Paul Krassner launched his long-running magazine of “social-political-religious criticism and satire” The Realist. It is telling of Kurtzman’s influence on American satire that the first issue of The Realist was produced in the offices of Mad magazine and was, in fact, born of Mad. Krassner had begun contributing to Mad magazine as early as 1955, shortly after Kurtzman left, but wanted to write more adult material, so he eventually abandoned Mad to create The Realist. His magazine’s first subscriber was comedian and TV personality Steve Allen, who sent gift subscriptions to others, including Lenny Bruce, who himself sent out more gift subscriptions. “From this momentum,” Krassner wrote in his memoir Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut, “the satirical wing of my readership would grow,” as would the influence of both Krassner and The Realist.

A significant aspect of the magazine’s humor was its cartoons, now collected in The Realist Cartoons, a handsome, over-sized book that is like a doppelgänger of The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker. If, as a memorable episode of Seinfeld would have it, the New Yorker prints cartoons that fancy themselves “commentary on contemporary mores,” the cartoons in The Realist trample those mores underfoot, as in the 1964 cartoon in which a gas station attendant asks the Buddhist monk handing him a gas can, “Regular?”

Over the course of 291 pages, The Realist’s cartoons touch on dark, difficult, sometimes taboo subjects—nuclear war, religion, sex, racism, death, abortion, the Vietnam War, and Watergate—with blithe indifference toward what can be said about those subjects other than to be provocative. “Irreverence,” The Realist announced on one of its covers, “is our only sacred cow.” It’s no wonder that, in spite of his immediate call for a paternity test, People magazine (of all things), declared Krassner the “father of the underground press.” Indeed, by the early 1970s, some of the most prominent underground cartoonists even contributed to The Realist, including Jay Lynch, Art Spiegelman, Skip Williamson, Dan O’Neill, R. Crumb, and S. Clay Wilson (probably the most outré of the lot, whose comics collected here are quite an eyeful).

While some of the cartoons are dated, requiring footnotes, that’s to be expected with topical satire. Many remain funny. It’s a pleasure to see New Yorker cartoonist Ed Fisher, whose work is featured prominently in this collection, letting his pants down, so to speak. And Sam Gross’s work, like the cartoon of a Seeing Eye dog watching his master step onto a busy street as he takes hold of a baby carriage whose handle resembles the dog harness’s handle, prefigures the gleefully tasteless material he did for National Lampoon. Probably the biggest surprise is the work of Richard Guindon, whose work in The Realist was earthier, more biting, and took more structural risks than his self-named syndicated comic strip from the 1970s and ’80s. His 1964, five-page feature “Guindon Goes to a Reservation,” in which the cartoonist visits a Seneca tribe who were losing their homes to a dam conceived by the Army Corps of Engineers that would “[dispossess] some 482 Seneca Indians, turning their homesites into river bottom and their treaty into nothing more than a fine example of old government stationery,” hints at the kind of comics journalism that would only fully flower in the 1990s.

The Realist and Trump, then, represent two strands of irreverent pop satire that are best exemplified by two of their more famous contributors—Mel Brooks in Trump and Lenny Bruce in The Realist. Trump, designed to be hugely popular by subverting what was popular, could be biting but was equally zany, leveling most of its criticism at the phony narratives and procrustean ideals disseminated through popular culture. On the other hand, The Realist was designed to subvert yet found popularity. At least three strips became best-selling posters, including the infamous Disneyland Memorial Orgy, a cartoon featuring some of Disney’s most well-known characters represented in flagrante delicto, freed from circumspect behavior by the death of God, better known as Walt Disney. Also, The Realist focused more often on social and political concerns, calling into question conventional assumptions about those concerns not only with its jokes but in its very willingness to offend.

In the ensuing years, both strands eventually came together, most notably in National Lampoon, the second-most popular magazine in the U.S. during the 1970s; like Trump, it offered pitch-perfect satires of pop culture but with an almost breathtaking disregard for taste that rivaled The Realist. National Lampoon eventually lost its most talented artists to Saturday Night Live, the late-night warhorse that, for better and worse, has overshadowed popular comedy for nearly half a century. At its best, what SNL shares with its 1950s forebears is a desire to get at the truth through laughter, however limited those truths might be, by shining a light on the lies foisted upon us. Rather than putting everything under quotations marks as they are accused of doing, these satirists use irony to reveal the quotation marks already around all claims to truth. Truth is truth. Claims to truth are just that, however well-intentioned, however accurate they seem to be. We need to be reminded of that to help us see the lies, to laugh at them, and to steal their fire, an ignobly noble project that Kurtzman and Krassner embarked on at nearly the same time when nobody knew they needed them.