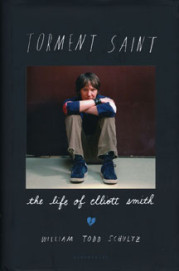

The Life of Elliott Smith

The Life of Elliott Smith

William Todd Schultz

Bloomsbury ($27)

by Scott F. Parker

Since 2010, William Todd Schultz has been the editor of the Inner Lives series from Oxford University Press. The series, which includes titles on John Lennon and George W. Bush and one by Schultz on Truman Capote, employs psychobiography: an approach to biography that, according to Schultz’s website, utilizes current psychological thinking to understand “the private motives behind public acts.” He is the author of Handbook of Psychobiography as well as a psychobiography of Diane Arbus that does not occur in the Inner Lives series.

Elliott Smith is an obvious subject for a Schultz psychobiography. Smith’s career flourished in Portland, Oregon, where Schultz was raised and resides today, and his work is preoccupied with the stuff of psychology—identity, attachment, abuse, trauma, depression, and suicide—to such an extent that at times it seems to plead for analysis. The divide between life and art for Smith was famously thin; the vulnerability he allowed in his music remains part of its appeal.

However, in Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith, Schultz elects to write straight biography, leaving his psychological expertise to underlie and inform the narrative without becoming its primary mode of investigation. This approach makes sense for a couple reasons. First, it allows Schultz to provide the thorough biography we’ve needed since Smith’s suicide ten years ago (the publication of Torment Saint corresponds with that sad anniversary to the month). Benjamin Nugent’s biography, Elliott Smith and the Big Nothing, was a solid effort but suffered for being rushed to publication a year after Smith’s death.) Second, because Smith’s music and life are already subject to so much reductive psychologizing, even Schultz’s professional take couldn’t help but read as derivative, if also well informed.

With his uncommon abilities, Schultz is uniquely capable of understanding Smith’s inner life and making sense of Smith’s mental health (depression, addiction, paranoia). Combine this background with Schultz’s manifest devotion to Smith’s songs (though he never says so, the reader gathers the author was in attendance at La Luna and Satyricon in the mid-1990s when Smith was performing with his band Heatmiser and starting out as a solo artist) and we’ve got the opportunity here for a warm and generous book. We also have the opportunity for fawning—Smith is compared favorably to almost every major songwriter you can think of, and the lyrical analysis sometimes overreaches for significance—but I raise this objection mostly to dismiss it. Schultz’s thorough research and carefully restrained interpretation make Torment Saint the kind of detailed and compassionate biography Smith’s fans would hope for.

Schultz begins his book by introducing the familiar myth of the troubled genius, which he believes was as seductive for Smith as it was easy for fans to apply to him. “Elliott saw through it, at times he dismissed it, but he also bought in, just as everyone else seemed to be doing. It was cool to be depressed. It was expected.” The context for depression as affectation is the rainy, heroin-filled Portland music scene during and immediately following Seattle’s grunge blossoming and Kurt Cobain’s era-shaping suicide. Smith was correctly described by John Graham as “an avatar for artistic Portland.” Schultz relates a definitive antidote of Smith walking Portland’s bridges under moon-filled skies regularly enough for friends to learn that he didn’t need a ride, this was his way of writing. His early catalogue from these years includes numerous drug references—perhaps most memorably on Elliott Smith’s “Needle in the Hay”—but according to Schultz’s sources, Elliott used hard drugs only as metaphor in this period. It wasn’t until years later while he was travelling in the U.K. that he started using, and not until his L.A. years that he became an addict.

By losing himself in drugs—crack and staggering quantities of prescription pills on top of alcohol and heroin—Smith fulfilled the prophecy of his music and escaped the pain he felt in living, if only over the short run. Life was increasingly painful for him as drug abuse compounded his depression. Smith, according to Schultz, was always divided: “part of him wanted to go on making music forever, but part of him always wanted it all to end.” He gave his life to music with a commitment that was either profoundly admirable or cause for distress, depending how one values survival—but in any case it was remarkable. “To say ‘it’s only the songs that matter’ is a cliche. But Elliott meant it and lived, and probably died it.”

As we read about Smith’s early years, his passion for music and his virtuosity are immediately apparent. We see him composing melodies, recording songs, and with time writing more and more lyrics. By his mature years, his talents coalescing, he is wildly prolific, writing songs by the dozens with an ease that impressed seemingly everyone interviewed in the book. For all the attention Smith’s depressive lyrics receive, it’s significant to note that it was his gorgeous melodies that drove him as a musician. He understood style through sound rather than intellect, saying in one interview, “You have to use your ears, not your head.” And in another: “It’s just that I like music. It’s not complicated.”

Unfortunately the music saved his life only until it didn’t. Schultz posits that Smith, who read Freud, thought that “if one could let it out, it might stop banging loudly on the door of consciousness.” Despite his intentions, catharsis never worked for Smith the songwriter. It’s too easy to think of his music as coming from a bottomless sadness, but it’s not exactly wrong either. Toward the end of his life, Smith would perform the song “King’s Crossing,” which includes the line “Give me one good reason not to do it,” to which his sister and girlfriend began responding, “Because we love you.” Whatever distinction there was been art and life was near gone in the leadup to Smith’s suicide.

If Dylan is our great ironist, Smith was among our most sincere artists. His story is a painful story, as those most inclined to pick up this book already know. In Schultz’s hands it is a well-told story, too. The author follows his subject’s lead and lets the reader know what it was like to be a person whose “songs were simply, essentially about what it meant to be a person.”