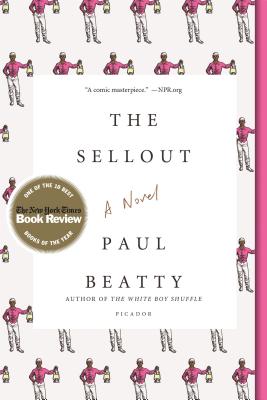

Paul Beatty

Paul Beatty

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ($26)

by Calista McRae

The Sellout opens in the hallways of the Supreme Court, where the narrator—the defendant in an impending trial, and the sellout of the book’s title—is fortifying himself with an especially potent joint. His explanation of his crimes forms the core of this bristling, exhausting, constantly funny novel: he has been keeping a slave and has been trying to reinstitute segregation in his home town.

Paul Beatty’s satirical novel is not easily summed up. Simultaneously gleeful, irritated, and resigned, its targets are all over the place, though a sophisticated humor smooths out the book’s cumulative anger, as well as its gruesome melancholy. The old man who becomes the narrator’s slave, for example, was one of the original comedians of The Little Rascals; he is equally ridiculous and mournful.

This satire is also ambivalent about comedy itself. While the goal of laughter is to puncture and expose, when Beatty’s characters laugh, the act is inane and fake as often as it is tonic. The most vivid emblem of complacent laughter occurs a few pages from the book’s end, at an otherwise black open-mic standup night: one white couple arrives late, and laughs too loudly and too knowingly.

And yet, comedy and delight vibrate in every corner of this book, from single phrase to plot. The narrator grew up in a ten-block neighborhood zoned for agriculture despite its position in the inner city of Los Angeles; named “Dickens,” it is also known as the “Murder Capital of the World.” When Dickens is taken off the map by richer areas that want “to keep their property values up and blood pressures down,” the Sellout discovers one of his first projects: to reinstate its boundaries. (Borders are a recurring theme in Beatty’s novels; in 2008’s Slumberland, the narrator tried to restore the just-toppled Berlin Wall.) There follows a barrage of jokes about Los Angeles, and about places and politics more broadly. Take, for instance, an extended passage on sister cities: “Some cities marry up for money and prestige; others marry down to piss off their mother countries. Guess who’s coming to dinner? Kabul!” The narrator finally tries a city matchmaking system, which offers Dickens three potential companions: Juárez, Chernobyl, and Kinshasa. Each rejects Dickens.

Within such set-pieces, all kinds of verbal humor contend for attention, from the miraculously apt to the miraculously absurd. An officer of the court is “a proud Budweiser of a woman with a brightly colored sash of citations rainbowed across her chest.” The celebrity intellectual who replaces “slave” with “dark-skinned volunteer” in Huckleberry Finn, and who rewrites The Adventures of Tom Soarer, uses an African-American presentation software known as “EmpowerPoint.” Driveby shootings have become harder to anticipate: “with these new hybrid, silent-running, energy-saving automobiles, you don’t hear shit,” and the gunman can clear out “while getting fifty-five miles to the gallon.”

Such passages suggest that language is a centrifugal force in this novel, but language also holds all these disparate performances together. Even the longest of Beatty’s sentences can be read out loud, with ease. As with the comedy of Dickens himself—or that of American satirists such as Flannery O’Connor and Junot Diaz—it’s hard to refrain from doing so.