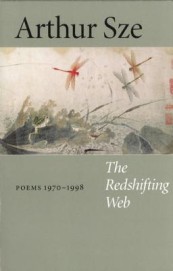

Arthur Sze

Arthur Sze

Copper Canyon Press ($17)

by Tony Barnstone

In "Kafka and His Precursors," Jorge Luis Borges tries to get at the sources of Kafka's peculiar vision and traces widespread affinities with earlier texts, such as the fantasies of Lord Dunsany, the essays of T'ang Dynasty poet Han Yu, the parables of Kierkegaard, and the poetry of Robert Browning. In the end, however, Borges is forced to admit that the strongest connecting thread within this diversity of precursors is Kafka's idiosyncratic vision. Thus, in a very real fashion, "each writer creates his precursors" instead of the other way around. I admit that in launching into this essay on the poetry of Arthur Sze, Borges's sweet paradox was the precursor to my own meditations, but wonder if Borges might have been cribbing his ideas on influence from T. S. Eliot's essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent," as Eliot probably was cribbing from Emerson's "Self Reliance." Where does the hall of mirrors end?

After many years of relative neglect, Arthur Sze, a Chinese-American poet who lives in New Mexico, has begun to garner the sort of national prizes (Guggenheim, Lannan, Wallace, NEA) and reviews that suggest that he is moving towards the center circle of the notoriously decentered American poetry scene. His recent successes are made all the more remarkable by the nature of his work. He does not write "the publishable poem." Instead, he is an experimental poet, an intellectual poet, an avant-garde poet, in a time when such poets (with the notable exceptions of John Ashbery and Jorie Graham) rarely gain the success afforded to narrative and confessional poets. When confronted with such work, the critic's habit is to attempt to master the strangeness by contextualizing it, seeking sources and affinities. Writers understand that with such domestication of strangeness comes an ability to discount its magic, and this is probably the source of that "anxiety of influence" that causes them to regularly and resolutely deny their influences. Still, in the case of Sze, such context is of interest mainly because it shows how he has mastered the masters, recreating his influences in his own image.

The Redshifting Web is a fine collection of poems, a fascinating document of how one Chinese-American poet determined his personal vision and at the same time found a usable past off of which to bounce his poetic radar. The early books excerpted in the collection—The Willow Wind (1972) and Two Ravens (1976)—are in the quite recognizable mode of free verse Imagism, Vorticism, and Objectivism, with beautiful, jewel-like, short lined poems largely set in nature and constructed according to the principles of implication instead of declaration, metonymy instead of metaphor, Ezra Pound's ideogrammatic method instead of Alexander Pope's rhetoric of argumentation. Sze's early poems about the great Chinese poets Wang Wei and Li Po signal, however, that he is looking past these English language aesthetic manifestations to the Chinese source. Indeed, Sze is a very talented translator of Chinese poetry, and it's clear that in his early work he learned a lot from meditating on the lines of the great Chinese masters. The interest of these early books, for me at least, lies in the intelligence that lies behind these pictorial arrangements, in how he blends modernist and Chinese techniques with the archetypal imagery of Deep Image poetry, and how often the clear image in his work edges into the surreal image, the "cottonwood" that "disintegrates into gold," the boat that is "moored to sky," how "the wind curls the stars in the cold air."

Arthur Sze's breakthrough book was Archipelago, not only in terms of public recognition, but more importantly in terms of the developmental arc of his poetry. The poems in Archipelago, and the new poems in this collection, are long, linked mini-epics, presented in a sequence that tie his book into a unified intellectual whole. Although it seems a natural extension of the earlier work in many ways, Archipelago represented a full commitment to an avant-garde intellectual poetics, and an extension of the movement away from short imagistic poetry and toward extended meditations that the books of his middle period, Dazzled (1982) and River, River (1987), initiated. I see an affinity between Sze's experimental poetry here and the fragmented juxtapositions of contemporary Chinese poets of the "Misty" school, such as Bei Dao and Bei Ling. I also see lines of connection with experimental Taiwanese poet Luo Fu and with the Language Poets. More important, perhaps, than these contexts, is the way in which Sze, the Misty poets, and the Language poets have all taken a journey past the restrictions of Imagism and classical Chinese poetry into new territory, while retaining essential techniques garnered from the encounter. It's the same voyage that William Carlos Williams took from 1917, when he asserted to Marianne Moore "I like a Chinese image cut out of stone," to his later contention that the alert reader is the one who doesn't abandon "a possibility of movement in fearful bedazzlement with some concrete and fixed present."

The recent poetry in The Redshifting Web is never dazzled by its own ability to make images, but subordinates those extraordinary visions to the river of ideas that makes the poem move. The poems are beautiful and difficult, and were modeled upon the Ryoanji Garden in Kyoto, a stone and gravel garden in which 15 stones are set in clusters, but in which you can never see all 15 stones at the same time. Like islands in an archipelago, the stones are set in the surface of raked gravel, suggesting hidden connections underneath. Each poem in the book, then, becomes an island or a stone arranged in subtle patterns that are revealed through your changing perspective as you walk or sail through the routes they make. As Sze wrote in "Viewing Photographs of China," "instead of insisting that / the world have an essence, we / juxtapose, as in a collage, / facts, ideas, images: / the arctic / tern, the pearl farm, considerations / of the two World Wars, Peruvian / horses, executions, concentration / camps; and find, as in a sapphire, / a clear light, a clear emerging / view of the world." It is this that makes these beautiful riddles worth the effort?not the trivia and precursors and analogues of the literary historian, but the shock of revelation that Sze's gentle, raw, whip-smart view on the world crystallizes in poem after poem.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol. 3 No. 3, Fall (#11) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1998