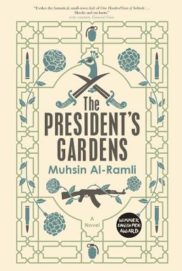

Muhsin Al-Ramli

Muhsin Al-Ramli

Translated by Luke Leafgren

MacLehose Press ($26.99)

by Mark Gozonsky

In One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez invented Macondo, a remote Latin American village, where he set the multi-generational saga of the Buendía family, who experience extraordinary events narrated with immensely charismatic composure. Check-check-check on these same elements for Muhsin Al-Ramli’s The President’s Garden, with one important difference: Al-Ramli’s remote village is in Iraq.

While many readers might expect a politically charged book, this book will also show a side of life that American readers don’t often see—that many Iraqi villagers like to drink cardamom tea, for example, or that to really enjoy a watermelon, they beat it open with their fists. Such details matter because they expand our idea of what it would be like to live in a nation so often vilified in the U.S. In such ways, The President’s Garden reaches across the propaganda divide.

Al-Ramli, an Iraqi emigre journalist and professor in Madrid, juxtaposes the traditional comforts of village life with the horrors of war and tyranny. The simple pleasures like cardamom and watermelon intensify the torture suffered by Iraqi prisoners in Iran, and the terror experienced by Iraqi soldiers attempting to retreat from Kuwait. “The skies rained down hell, the earth vomited it back up,” Al-Ramli writes relatively early in the book, prefiguring a character’s urge to puke that figures crucially in the novel’s finale—a climactic scene that signals a refusal of business-as-usual after the fall of the notorious Iraqi tyrant, whom Al-Ramli declines to name.

In the end, The President’s Gardens presents apocalypse after apocalypse, yet leaves open the possibility for redemption. While its ending is a bit abrupt, leaving readers literally at the side of the road, it also comes as a reprieve, the very thing explicitly denied in the whirlwind end of One Hundred Years of Solitude: an opportunity for change.