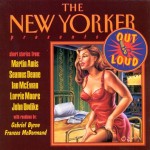

various artists

various artists

mouth almighty records

by Kelly Everding

The New Yorker's reputation for presenting brilliant new fiction every week is unmatched, and this double-CD helping of stories from recent issues can only serve to augment that reputation. I thoroughly enjoyed revisiting these works by Martin Amis, Seamus Deane, Ian McEwan, Lorrie Moore, and John Updike—all storytellers of the highest order. Interweaving humor, observation, and the profundities of human emotion with the banal and extreme moments of existence, this fiction takes on peculiar shapes when read out loud and fleshes out further the varied talents of these writers.

McEwan, Amis, and Updike read their own stories. Their voices are a surprise—not exactly what you'd expect, but then exactly what you want. McEwan's musicality matches the fugue-like narrative in "Us or Me" (actually an excerpt from his new novel, Enduring Love), moving teasingly toward and away from the undeniable and unchangeable outcome. Amis's nearly monotonous intonation, at first unnerving, provides a counterpoint to the memoir-like account in "What Happened to Me on My Holiday," told by a young boy confronted with death for the first time. Updike's high and breathy voice, on the other hand, is nearly jazzy as his narrative relinquishes the tale of an affair in "New York Girl."

The stories by Seamus Deane and Lorrie Moore are read, respectively, by Gabriel Byrne and Frances McDormand, and the humor and humanity of these stories reach a pinnacle in these actors' expressive interpretations. Byrne plays the characters well, switching from the stern and long-suffering priest/math professor to the timid students doomed to failure in Deane's hilarious "Maths Class." McDormand moves expertly between fierce raillery and wrenching helplessness in Moore's "People Like That Are the Only People Here," the story of a mother whose baby is diagnosed with a cancerous tumor.

Though fragments of Charles Ives's The Unanswered Question are used to good effect in "Maths Class," the bits of music interspersed at key moments in "New York Girl" and "People Like That Are the Only People Here," although ultimately unobtrusive, tend to magnify the moments of sentimentality. Personally, I found the stories and their tellers talented enough to convey emotions without the music providing manipulative, conscious cues. But despite that, this set of readings—hopefully the first of many, as The New Yorker has a deep well from which to draw—is a worthwhile endeavor. I highly recommend that readers to let themselves be read to. It's something one can never outgrow.

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol.3 No. 1, Spring (#9) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1998