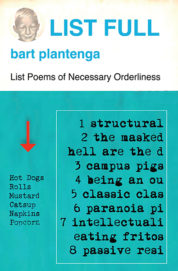

by bart plantenga

by bart plantenga

“How, as a human being, does one face infinity? How does one attempt to grasp the incomprehensible? Through lists.” -Umberto Eco

“I perceive value, I confer value, I create value . . . hence, my compulsion to make lists.” -Susan Sontag

Lists are not poems, especially when you begin calling them “poems.” Rather, the more unlike poems they seem to be, the more like poems they begin to act—even more than most poems themselves. In fact, the “poem” in its present guise is often comparable to Hollywood acting: the more self-aware and over-weened the performance is, the less likely you’ll believe the character. Lists are wonderful because they’re not hamstrung by poetic dogma and so possess a potentially more dynamic arrangement of words than many poems. If a poem is a lazy dish of meatloaf floating in thick gravy, then the list is a pan of popping popcorn about to lose its lid.

Most lists and their related articles are prescriptive, self-help, and, in recent years, often clickbait; as Maria Popova observes, it’s “today’s favorite attention-exploitation device in an information economy of countless listicles.” List evangelicals often advocate the list’s life-changing qualities. That’s fine; after all, the list has assumed the respectable chore of reestablishing order, indispensable for our cluttered world of hyper-exposed data—a helpful, therapeutic lifestyle management tool. Without lists we’d be as lost as a sea captain without a sextant.

So, what if ordinary personal-intimate-useful lists are allowed to wiggle, misbehave, and – like the singing short-order cook in the kitchen – emerge as unselfconscious, working-class poems of utility and humility? Think work song heard in a cotton field as opposed to chamber music performed in a drawing room. I decided to look at this utilitarian form anew for my latest book because:

- No one had ever done a book of lists as potential literature

- It was waiting to be compiled

- I’m a glutton for punishment [the work-reward ratio]

- I’m dyslexic and dyslexics must rely on lists to order what the mind cannot unaided

- I’m tired of most of the weather that hangs over poetry

- It’s a reaction to owners of a poetic license—I may have a driver’s license but that doesn’t make me a Formula 1 driver.

Lists were never conceived as poems, and thus can serve as critical interlopers, unbeholden to linguistic peer pressure, untethered from ulterior motive. Maybe they can even serve as poetic justice, as antidotes to self-serious poems that insist they can DO so much: change regimes, shift paradigms, illuminate the dusky, voice the unvoiced, rouse the masses, transform lives, foster teaching careers, etc., etc. Lists are contrarian in the same way punk originally confronted the over-weened emotionality of classic rock guitar solos.

Lists ignore the syntactical and ontological presets informed by The Chicago Manual of Style, thus freeing them from literature’s contrivances. This encourages disruptive leaps of logic, skewed word orders, sparking synoptical leaps between disparate words. Poetry is usually A to B, while lists perform staggering leaps and bounds from point C to point X, with no hint of explanation or apology.

For instance, in “Abridged List Pre-Move Busy 1996, NY-NL,” from List Full words found in close proximity include: “see Olympic torch spectacle - retirement village / hike, dead end dream in sun - rum & OJ / bad fish restaurant methodist church for photo op / retirees” and “walk lake owls swamp shishkebobs rockers church bells.”

For instance, in “Abridged List Pre-Move Busy 1996, NY-NL,” from List Full words found in close proximity include: “see Olympic torch spectacle - retirement village / hike, dead end dream in sun - rum & OJ / bad fish restaurant methodist church for photo op / retirees” and “walk lake owls swamp shishkebobs rockers church bells.”

These are not glossolalic upchucks; they match our contemporary sensory aptitude to glean meaning from rapid-fire music samples, movie trailers, and news montages. We process data faster than people did years ago. And we know that the rapid flip of static images at 24 per second fools the mind into experiencing a moving image (the phi phenomenon). Just as still images become film, so do seemingly unredeemably unrelated words, discomfitingly placed side by side, find poetic purpose. This can be seen in the line: “carpet samples, candy, x-rays, deli take-out.” Lists thus assume a freedom beyond free verse to gain vigor and sustenance, to create bold, almost Dadaistic poems of liberating absurdity.

When our minds couple the phi phenom with an upbeat version of the affliction known as apophenia, which psychologist Klaus Conrad described as “the unmotivated seeing of connections,” we enter an alchemical process, a collaboration between listener and reader, where words are elevated beyond their mere utility as reminders.

Shorn of all presumptuous ballast, the list can now perform poetry’s essential task: shooting to the clear heart of matters. Lists become maps to previously undetected diary entries. They can be as illuminating as the blue glow of luminol at a crime scene. The end result, the harvest of all this grammatical tumult, can be surprisingly anomalous: lists, secure in their concision, stoically uncover a mantra-like calm, a stilling of the mind, while unearthing snapshot mini-memoirs. Just as a documentary can portray the dignity of a working-class person without claiming the worker is some kind of royalty, List Full attempts to spotlight the neglected list as something of essence without claiming it as precious poetry.

Lists are usually read in silence, are seldom recited, are not marveled at or nominated for awards, and are most often of temporary utility. They almost always find themselves balled up and tossed into a wastebin. But I implore you to give them a second look before you discard them.