by Zhanna Slor

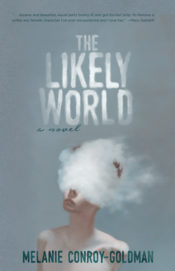

What does it mean to be Jewish in the modern world? This is a question I found myself asking while reading Melanie Conroy-Goldman’s debut novel, The Likely World (Red Hen Press, $18.95), which I discovered in an online Jewish writers’ group last fall. The book, which deals with familiar themes about Jewish identity while also maintaining a compelling story, is grittier than most Jewish novels (crime and drugs abound, for example, and the plot leans more mystery than literary); it also deals with Jewish topics that are less trodden, since the focus is only obliquely on the characters’ Judaism and the most “Jewish” thing that happens is that they all meet at Jewish camp. The culture of Judaism fades into the background, which is sort of unusual in itself, and worthy of discussion.

Conroy-Goldman’s novel also delves into other fascinating topics, including attraction, addiction, motherhood, memory, and more. Driven by its strong protagonist Mellie, a single mother hooked on the drug “cloud,” The Likely World is an extremely compelling first book, and I was pleased to discuss it in depth with the author.

Zhanna Slor: I kept thinking of cloud as The Cloud—as in, smartphones. I felt like a lot of what cloud does to Mellie is what phones do to people: they make you super anxious to check all the time and get your dopamine hit, make you unable to function without them, make you unable to be in the moment, make you forget what you did for three hours. Was this your intention?

Melanie Conroy-Goldman: Yes, and I'd broaden it out. The modern condition to me feels deeply enmeshed in the present. We're absorbed by the 24-hour news cycle, by constant entertainment, over-scheduling, overwork. The disastrous nature of 2020 illustrates the barrage of the present, but if you think to the news of school shootings, for example, we live in an age of such incessant disaster. We can barely retain anxiety for one thing before it’s erased by the next. The internet is a part of it, but the cloud also references obliquely the environment, our inability to see outside of the now. The irony is that our absorption in the present not only erases the past, but also obscures the future and makes it difficult to envision a better way.

Melanie Conroy-Goldman: Yes, and I'd broaden it out. The modern condition to me feels deeply enmeshed in the present. We're absorbed by the 24-hour news cycle, by constant entertainment, over-scheduling, overwork. The disastrous nature of 2020 illustrates the barrage of the present, but if you think to the news of school shootings, for example, we live in an age of such incessant disaster. We can barely retain anxiety for one thing before it’s erased by the next. The internet is a part of it, but the cloud also references obliquely the environment, our inability to see outside of the now. The irony is that our absorption in the present not only erases the past, but also obscures the future and makes it difficult to envision a better way.

ZS: The other way I see cloud is as an illicit version of an anxiety medication. She takes it whenever she gets anxious, it seems, especially when it comes to her own sexuality and lust towards Paul.

MCG: I was definitely thinking about both anxiety and our culture's tendency to medicate difficulty. I have been enormously helped by medication, and I know for many people it's a lifesaver, but it's also a capitalist solution—an expensive product, accessible only to those who have insurance. We tend to reach for a thing when we're worried or unhappy. I do wonder what we would do, what we might change, if we shifted the model. If we took action, if we reached for a person or a community instead.

ZS: What is it about Paul that she is so attracted to? I didn’t really get what she liked about him. Is it just a physical attraction? And why is Mellie so daunted by it?

MCG: This is interesting. Different readers have responded to Paul and Mellie's passion for him in different ways. He's smart, pretty, and wounded. That's definitely a type some people get, but it's also surely an immature attraction. I liked sad boys when I was a teenager because they went along very nicely with my angst and the perpetual soundtrack of The Smiths, The Cure, Billy Bragg, etc. that formed my idea of love. Cloud addicts don't mature, are frozen in this teenaged time. This paralysis is part of why she can't let go, but it's also another form of addiction. Mellie is addicted to Paul. It may not be rational, but how many of us love rationally? Indeed, we realize that the Paul we see through Mellie's eyes is as much a projection as it is real. He needs to be let go, for himself and for her, but she clings in a way that damages them both.

ZS: Does it have something to do with Jewish parents' inability to talk about sex or bodies with their kids? (I know that is an overgeneralization, but from my perspective, it seems like something that’s not really discussed)

MCG: My parents were actually pretty good on this. I grew up in the 1970s, and my folks were pretty feminist. I had a well-read copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves. But I think a lot of my education was anatomical in nature, i.e. “This is how you get diseases, this is how your body works.” Though that's probably important, it didn't turn out to be what's critical. I think Jews are pretty family-oriented, culturally. And I suppose my models just fast-forwarded to married life. There wasn't a narrative about desire or dating, or the navigation of the murky space before you partner up for perpetual Shabbats with your children around you. I wrote a bit about twentieth-century Judaism's inability to discuss female desire in an article on Herman Wouk's Marjorie Morningstar, in which sex absolutely destroys the protagonist's soul and dooms her to a life of disappointment. I think there's a lingering shadow of that, even in a culture that's apparently evolved. Marjorie also falls for a guy who no one thinks she should stay with, by the way.

ZS: Another thing that struck me was the title, how every time “The Likely World” is mentioned, it’s used as a negative way of looking at life, of having this idea of a perfect reality, maybe one that you come up with when you are a teenager and haven’t seen much of anything. People are always telling Mellie to try and live in this world, the one in front of her. (I saw this as a modern version of “Get your head out of the clouds!” which is another way that the drug name really hits the spot.) Why do you think Mellie was so incapable of doing that? Did her fear of failure overwhelm her so much that she sabotaged herself with this drug addiction, or did she not intend to sacrifice her ambition at all, and it just slowly crept up on her?

MCG: I think you've located something important in the idea that young people dream perfect futures for themselves. As you mature, you realize you can't be both an astronaut and a famous ballerina. This is a loss, yes, but not necessarily a tragic one. Just an astronaut is pretty good. But if you can't absorb change, can't choose among your possible futures or accept that you may not get each and every thing you want, then you can become paralyzed and end up with nothing. Like Mellie, I wanted to be a politician as a teen. That would have been a terrible career for me, and I have a job and a vocation that I love. We have the Disney version of childhood dreams, where the best outcome is to follow through, but that's for kids. As we grow, change, learn more of the world, I think we find out who we are, and what makes sense for us. Addicts don't get to do that, don't discover. So I see Mellie's journey as less a failure of ambition as a failure to evolve.

ZS: I agree that it’s a sign of immaturity to be unable to decide a path for yourself and stick to it. My husband is a professional sax player, so I’ve been a witness to how difficult it can be to have an unusual or highly challenging career path, like Mellie’s political aspirations—and of course, writing is no easy vocation either. It requires a lot of sacrifice and perseverance. Do you think something in Mellie’s life stunted her ability to mature properly, other than her addiction? Like Paul, she seems stuck in the past, in a very teenage mindset. I thought, for example, as I was reading that it might have to do with her lonely childhood. Her mother is a little bit absent emotionally, her dad is not around, and her friends are kind of jerks. I felt bad for her that she didn’t have any positive influences in her life!

MCG: When I think about this, I guess I think in terms of preconditions. Mellie was primed, by parental absence, to be vulnerable to addiction. By the time people show up who can offer her a hand (there's a teacher in college, and her grandmother, we learn, is a special presence Mellie simply can't or won't connect to), she's already in the grips of the drugs, and the drugs freeze her in time. But I also think there are societal preconditions. The way we sexualize young women, the so-called double standard by which girls are both pressured to be sexual and also shamed for it. Mellie needs love, I think. She tries to win it through sex, and then through suppressing her selfhood in order to be appealing. But I don't know that I believe she needs love more desperately than other girls her age. I could be wrong. Maybe I was weird in this and other young women had their heads on their shoulders, but I just wanted boys to like me—to love me—like in a rom com. I wanted it so completely and entirely. When I recall the extreme anguish I felt about objectively kind of goofy boys who I didn't even really know very deeply, it astonishes me. That I managed to do schoolwork, eat, try out for the play, all the normal teenaged stuff, with these just monster feelings and desires in me seems unbelievable. My girls (12, 17, 19) seem generally much less insane on the topic. Have times changed? Or are they just sharper young women? I can't be sure.

ZS: I can definitely relate to that, as a very boy-crazy girl myself. If I had actually received attention from boys, maybe I would have been less obsessed with it? I don’t know. I was a lot like Mellie actually, but I didn’t have access to drugs, so I turned all those big feelings into paintings of Kurt Cobain. Speaking of art and artistic teens, because of my own background I really identified with Mellie’s constant flirtation with poverty working in the arts and how this is not a very typical portrayal of modern American Jews. I think the stereotype is always that Jews must be rich. (I too went to Jewish camp on a scholarship, as I believe Mellie did.) Part of why I enjoyed your book so much was that it strayed away from this typical Jewish suburban upbringing in its portrayal of Mellie. Jews are not all the same after all; immigrants from the USSR, for example, come here with almost no money, and even if they become middle class later in life, their kids are not always raised this way. And plenty of others struggle financially too, I’m sure. Were you thinking about breaking through these stereotypes while writing this book?

MCG: I love this question. In the 1970s, many Jews were recent immigrants, because of the Jackson-Vanik Amendment, which facilitated immigration from Soviet Russia, where, as you know, Jews were very marginalized, prohibited from career paths, and forbidden from practicing. I think the Jew of the popular imagination derives from a subset of people who had deeper roots in this country, and thus more resources (but it's still a stereotype, and therefore exaggerated and rooted in anti-Semitism). Many of us are/were poor. It never made it to the final draft, but originally, there was a lot of conversation about this particular demographic—recent immigrants—in earlier versions of the book. Because many of these recent immigrants weren't practicing, they were doubly alienated from both their heritage and from their new country.

On the other hand, Judaism has a kind of precedent for genteel poverty. I think this tradition has manifested in a kind of comfort with an artistic or intellectual life rather than the pursuit of wealth. If this representation works against those bad stereotypes, even in a tiny way, I'd be very glad of it.

ZS: My book also portrays Jewish characters in the lower rungs of society, and sometimes drugs are involved as well. Did you get any pushback from the Jewish community about this?

MCG: There were definitely venues that didn't want to review or feature the book. I had a panic attack literally the day before I finalized publication, in which I was gripped by a fear of what the Jewish community would think. I wanted my relatives to read redacted versions. So, totally. I think you always worry, as a part of a minority group, about representation, and feel a burden to present your people in a positive light. But writers aren't in the business of public relations. And, as others in the same position have said before me, and better, to portray people as individuals, flawed humans who have as much right and capacity to fail and succeed as any other people, is also an intervention against bias. Like everyone else, we are people with bodies whose appetites and needs can betray our better instincts.

ZS: What do you think would have happened to Mellie if she never tried cloud?

MCG: This question makes me sad for her. I don't think she really would have been a politician. There's a scene with a professor, a mentor who gives up on her, and I guess I imagine if she'd been well, she could have accepted this offer of help, and gone on to be a scholar. She's actually studying Soviet Immigration at the time, so maybe she would have been able to offer some insight or serve as a bridge between immigrants and their new country. Or maybe her artistic side would have won out. But her daughter is the inadvertent gift of her bad choices. And I see Juni as being worth any loss that might have occurred on the way. Mellie is a mom, and the most hopeful thing for me is if she can figure out how to live up to that.

ZS: This reminds me that I never brought up Mellie’s motherhood. I totally agree that Juni is worth all the missteps. I have a daughter almost the exact same age as her, so as I was reading, I was actually filled with quite a bit of anxiety about the poor baby. I have similar moments, where I’m really involved in something else, like writing or working, where I am not giving my full attention to my daughter, and afterwards I feel like I was so lucky that nothing happened to her while I was distracted. So, I think that is really relatable even for those who do not struggle with addiction. Do you have kids, and did you feel nervous writing a character who can come off as neglectful?

MCG: I'm a mom of one, and stepmom of two. I know for some readers, kids in peril are just a no-go. One of my writing group members—a Jewish mom, like me—said she really had to push through that part. My own daughter, when she was just over one, began to lose weight precipitously. She lost four pounds between 12 and 18 months. It was terrifying. We saw the department heads of three different specialties at Children's Hospital in Boston before a very careful, smart intern finally found the problem. It was simple, in the end, and she's a healthy twelve-year-old preparing for Bat Mitzvah now. So, that's what I drew on to write about that. Even if I wasn't neglectful, you feel like a terrible mom when your child won't eat or can't eat. Maybe especially for a Jewish woman, for whom feeding is so central to motherhood. I know moms who joke about their kids' scant appetites. Not me! Even so, I do think there's a universal experience embodied in the neglect: a parental anxiety that we will fail our children in some fundamental way, fail to protect them or prevent their pain. And universally, we do fail, we do fail to prevent it. So, even if I lost some tender readers for whom child peril is too hard (and I get that!), I felt it was important to explore this territory.

Most people tell me they find the character sympathetic—they root for her. I guess part of my project with her was to consider the most unforgivable transgression: harm to a child has to be it, in my book. I wanted to know if a person who has done that kind of harm can be redeemed, can redeem herself, can earn a reader's forgiveness. The risk in that project is that some readers won't forgive, but I think that response is still a meaningful one, even if it's not what I intended or how I feel about the character.

ZS: I found her quite redeemable! Many women in her place might have just given up, and she didn’t; that says a lot about her character.