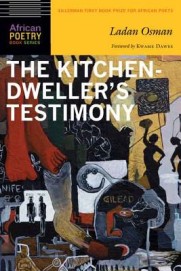

Ladan Osman

University of Nebraska Press ($15.95)

by Wesley Rothman

Paradise is to ask whatever you like. A tea with God.

I have filled a book with questions I can’t remember.

—“Following the Horn’s Call”

In his “Preface” to Ladan Osman’s chapbook Ordinary Heaven (part of the Seven New Generation African Poets series, published by Slapering Hol Press and sponsored by the African Poetry Book Fund, Prairie Schooner, and Poets of the World/Poetry Foundation), Ted Kooser reflects on the poet’s inquisitive nature: “And inquisitive is perhaps too weak a word, so let me use questioning. Her work is questioning. She asks about everything; she wants to know about everything.” This is utterly true of the poems in The Kitchen-Dweller’s Testimony also, yet Osman’s work points to something well beyond, an insatiable desire to understand—this collection, awarded the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets, ventures to instigate and demand ways to answer these many questions.

In his “Preface” to Ladan Osman’s chapbook Ordinary Heaven (part of the Seven New Generation African Poets series, published by Slapering Hol Press and sponsored by the African Poetry Book Fund, Prairie Schooner, and Poets of the World/Poetry Foundation), Ted Kooser reflects on the poet’s inquisitive nature: “And inquisitive is perhaps too weak a word, so let me use questioning. Her work is questioning. She asks about everything; she wants to know about everything.” This is utterly true of the poems in The Kitchen-Dweller’s Testimony also, yet Osman’s work points to something well beyond, an insatiable desire to understand—this collection, awarded the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets, ventures to instigate and demand ways to answer these many questions.

By reading these poems we run into answers we often don’t realize we need. Osman often achieves this through dazzling leaps of lyric:

Neither of us knows the best prayers,

but we can pretend, we can let them strain

in the back of our throats as melody.

—“To Abel”

Earlier in this poem the speaker asks, “Who hears it when you keep its hum / at the base of your throat?” and answers by the line, “I do.” Throughout this book, Osman’s speakers ask, answer, and propose next-step possibilities for questions, in ways that confirm melody is something productive and endearing—as if to say that even when there are no words, there can be action.

With “The Key,” one of a few prose poems in the collection, Osman carries us from a father trying to find a job and a mother’s optimistic, “maybe we just haven’t found the right key, I’ll go look for it,” to a daughter’s collection of keys, which she tries on different locks. Eventually one works on a door in an abandoned mall:

It was a room with white walls, floor, ceiling. White squares of wood flat or leaning in every corner. The door closed behind me and no key would work. Maybe the room would swallow me and I’d get invisible if I didn’t stop screaming but then a surprised guy, white, wearing white, opened the door.

Narratives like this carry us into spaces we rarely access in daily life. The speaker (and the reader) enters a white room and effectively becomes trapped there, a fitting allegory concerning race in contemporary society. Similarly, the poem “Connotation” addresses a white woman spitting at the feet of the speaker, saying, “This neighborhood has changed since these people came.” In the context of the collection’s epigraph by Walt Whitman (“What living and buried speech is always vibrating here . . . . what howls restrained by decorum?”), Osman’s speaker can not respond because of decorum’s dictatorship: we place blind faith in decorum, yet that faith calls our attention toward appearance and away from facing and testifying to more important human truths: empathy, understanding, and appreciation, or varying degrees of lacking these. Very rarely, it seems, are people able to tend both their appearance and their actual minds.

With wildly imaginative and immediate sequences of story, image, and language, Osman delivers us to a space with which we are likely not too familiar, a space where we must ask questions of ourselves—how do our actions and attitudes speak for us? Does our opinion of ourselves really match the reality? —and be open to hearing honest answers (probably less favorably than we think, likely not). In “The Kitchen-Dweller Presents Evidence,” the speaker realizes, “Destruction: she answers questions I didn’t ask,” and like the speaker, we must figure out how to live with those unsolicited answers.

This collection commands honesty at all costs, on the parts of speakers and readers. In “Her House Is the Middle East,” we learn of a wife so used to her husband’s infidelity, the house is a place used to both conflict and inaction. Osman brings our attention to the reality of being conditioned to violence, to abuse, to decorum, to corruption, to suffering. Once we have been conditioned, how do we recognize injustice, how do we testify that it thrives, and how do we overthrow the force that has conditioned us?

Ladan Osman conveys a language and logic that is disturbingly fresh; it leaps from one observation to another and speaks familiarly yet obliquely enough to make us listen a little harder. These poems mimic what we hear in “That Which Scatters and Breaks Apart”: “From every space someone calls a question / and there echoes so many answers, it’s impossible to hear.” It seems impossible to hear, or at least difficult, but if we silence ourselves for a few moments, and listen completely to the voices coming through these pages, we will hear answers to some of the most trying questions of our time, and might discover a way to be better lovers and neighbors and humans willing to testify.