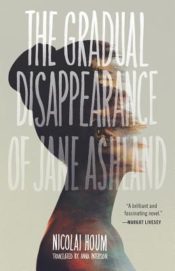

Nicolai Houm

Nicolai Houm

translated by Anna Paterson

Tin House Books ($15.95)

by Rick Henry

There are no spoiler alerts needed here: The Gradual Disappearance of Jane Ashland opens with the title character, a writer and teacher at the University of Wisconsin, alone and slowly freezing to death in the northern wilderness of Norway. ”Now, while she is still conscious, she must lock her fingers in a dramatic pose. “Oh my God, it looks as if she tried to grab at something at the moment of death!” she imagines the responders saying when they’ve found her. Her final thought offers two questions inextricably linked: “What should she reach for, how should she make it look?” For us, there is a third: Who is Jane Ashland? What has disappeared is her very self, a loss so profound that there is literally nothing for her to hold onto.

Norwegian novelist Nicolai Houm posits Jane’s loss as the inevitable result of two traumatic events. The first, the ”what should she reach for,” is the death of her husband and her daughter in a car accident. The second, the “how should she make it look,” might best be given over to her own words: “when you begin to think that your writing is no more than a construction you use to say something about another lot of constructions, and that, meanwhile, the most profound truths of the human condition are forever beyond your reach—then you stop writing.”

Jane spends much of the novel trying to recover her courtship and marriage, the birth of her daughter, and the inevitable phases of their mother/daughter relationship. Her initial attempt to cope with these losses is to insert herself into another family. She finds distant relatives in Norway; on the plane ride there, she encounters a forty-something zoologist who invites her to accompany him into the wild. He has spent the previous two years studying the herding behaviors of musk oxen, and by the novel’s end, these behaviors become something of a metaphor for Jane’s situation—perhaps, even, a metaphor for the most profound truths of the human condition.

Her attraction to her Norwegian relatives is, in part, the fact that their family unit of father/mother/daughter reprises her own. She inserts herself into this family’s dynamic, stepping in to “rescue” this daughter from the pressures of playing sports, but her attempt is doomed to failure—Jane’s construction of her previous life does not match her current situation, and moreover, the “mother” slot in this family is already taken. She is left with the stranger, and a kind of courtship that doesn’t (and can’t) match the courtship story she’s framed for her husband. Her rejection of the zoologist is hardly a rejection—she no longer has the energy or interest in engaging the “real” world, even as it has its way with her. And so we are left with her contemplating the world of appearances.

However much Houm exploits Jane’s inability to maintain contact with both the real world and the world of appearances, the novel shouldn’t be read as an exercise in deconstruction; the author’s major success is in the dramatic presentation of a character struggling for her own existence. The Gradual Disappearance of Jane Ashland is the first of Houm’s novels to be translated into English. Based on its strengths, one expects the hasty translation and release of his two previous works.