by Scott F. Parker

by Scott F. Parker

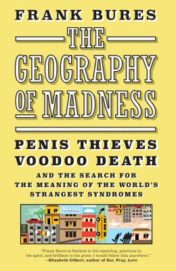

Frank Bures writes for many publications, including Harper’s, Runner’s World, The New Republic, Outside, and Poets & Writers. His essays have appeared in Best American Travel Writing and been noted in Best American Sports Writing and Best American Essays. His book The Geography of Madness: Penis Thieves, Voodoo Death, and the Search for the Meaning of the World’s Strangest Syndromes (Melville House, $25.95) has been getting a lot of attention from radio hosts who are excited to read its subtitle on air. I called him recently at his home in Minneapolis.

Scott F. Parker: Jambo, Frank!

Frank Bures: Hi, Scott.

SFP: Your author bio on the book jacket says you speak several languages. I know Swahili is one, and I think you speak Italian and Spanish. Are there more?

FB: Well, I speak decent Italian and Swahili, and I can kind of get by in Spanish. When I was in Thailand I could chat in Thai, not very complicated conversations, but more than most expats there. I have also lived with Germans and understand some of that. And I’m trying to teach myself French.

SFP: Does it seem like language comes easily, or do you put in a lot of time studying?

FB: Once you’ve learned one language it’s much easier to learn another. You can figure out what are the things you need to know. (And the things you need to know to fake it.) The languages that I’ve learned the best—Italian, Swahili, and Thai—they’re all difficult, but in different ways. In Italian there are a lot of verbs to memorize, and the conjugation is a little bit tricky sometimes. In Swahili conjugation is really complicated. And in Thai, the verbs are simple, but the tonal aspect is very difficult.

SFP: How is your interest in language related to your interests as a writer?

FB: When you learn another language you really have to learn another way of thinking, and the ideas that the words contain are based on a lot of assumptions that are not in the words themselves. There’s no direct translation for a lot of things. You have to understand the idea that’s trying to be communicated, not just the word. There’s a lot of context behind it. You’re not just learning a language; you’re learning a way to see the world. So that gives you a lot of insight into a culture and the way thoughts can flow—the different possibilities each language allows. I’m not of the school that believes that language is thought, but I do think it lays out some of the channels through which our thoughts can flow.

FB: When you learn another language you really have to learn another way of thinking, and the ideas that the words contain are based on a lot of assumptions that are not in the words themselves. There’s no direct translation for a lot of things. You have to understand the idea that’s trying to be communicated, not just the word. There’s a lot of context behind it. You’re not just learning a language; you’re learning a way to see the world. So that gives you a lot of insight into a culture and the way thoughts can flow—the different possibilities each language allows. I’m not of the school that believes that language is thought, but I do think it lays out some of the channels through which our thoughts can flow.

SFP: You write that upon returning to Minnesota after studying abroad in Italy, something was lost. Have you ever found what was lost?

FB: I don’t know. One of the things I lost was a kind of certainty that I don’t think is possible to find again once it’s lost. It’s the rock-solid assumption that the world works in a set way and you don’t even have to think about it. When you only have one set of stories to live by, your idea of who you are can be more solid. In that sense I guess since coming back from Italy, I’ve always been looking for other possibilities for who I could be.

When you get to the point in a language where you start dreaming in it and thinking in it, it feels like you have a different personality in that language. It almost feels like a new way of being in the world. And so maybe that’s what I’ve found.

SFP: It’s a destabilizing thought, how culturally created we are.

FB: Absolutely. You wonder, "Who would I be if I was born in these other places?” Would you be totally different? Would certain core personality traits be the same? There’s no way to answer those questions, but it certainly makes you ask them.

SFP: This relates to some of the central themes of the book: the importance of storytelling and the degree to which worldviews are culturally situated.

FB: The stories we tell shape our understanding of what causes things to happen, both inside and outside of us. When you’re around other people who don’t believe those stories, you have to question whether they’re true or not.

SFP: I know when you talk about koro [i.e., the belief that one’s genitals are disappearing] people often ask Why don’t they just check? It seems like what those who ask that question are really saying is that this culture stuff is great and all, but the scientific method is qualitatively different because it gets results—it’s verifiable, or at least falsifiable. So how do you respond to that question in general terms?

FB: I’m definitely a fan of the scientific method. I was raised in that culture, and I believe in the power of science. But when you apply it to medicine and illness and mental health and those kinds of things, you can see that part of the power of scientific medicine or biomedicine is the belief in it. The more strongly you believe in it the better it works. And you can measure that.

SFP: Doesn’t that further confirm the method itself?

FB: Yes. But what I’m talking about in the book is causal perception and its effects, not actual causation. Science tries to sort out what the causal mechanisms actually are, so they can be used in technology. And if belief is one of those causal mechanisms, then science should be able to show that.

SFP: This comes back to the idea, longstanding in the West, that the body is a kind of machine, reducible to physical processes—an idea you reject in the book.

FB: This gets into a different problem. The biomechanical understanding of things is partly rooted in the desire to do away with dualism, the idea that there is a person inside the body. Neuroscientists especially argue that they’ve solved that problem and there’s this causal flow from physical to mental that’s one directional. And that’s just clearly not the case. So the question is how you account for that. To me it seems like the neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga has a good handle on this. He explains it in terms of “strong emergence” versus “weak emergence.” The idea is that complex systems arise from small repeating actions. A weak version argues that you should be able to look at the parts and understand the whole; for example, you should be able to look at an ant and understand the colony. In a strong version, at some point a system takes on a different quality and starts operating by a new set of rules. He calls this a “phase shift.” Once that threshold is passed, the rules that applied to the individual parts no longer apply to the system. The best example is quantum mechanics, where one set of rules applies at the subatomic level, but once you cross over into the realm of general relativity you have a different set of rules. Nobody’s really come up with a way to unify the two, and they probably won’t.

Gazzaniga argues something similar for the brain and the mind. The mind is something that emerges strongly from the brain, and you can’t go back and look at the parts to explain the mind. That also means the mind can act backward on the brain and change it—we can see that. So you have two directions of causal flow, top to bottom and bottom to top, rather than just from bottom to top—from physical to mental.

SFP: What do you think will replace the metaphor of body as machine? I wonder how living so much of our lives online affects how we think about the world.

FB: The Internet could be a new kind of machine metaphor—it’s a dynamic network as opposed to a single computer. But using the Internet as a metaphor is problematic because it’s mostly humans doing things through their machines—so you have that additional layer of complexity, not just the machines. We usually talk about brain as a computer, but I think that’s totally false; it leads you down all kinds of deterministic paths that I’m not crazy about. It doesn’t allow for any agency. The differences between a computer and a brain are so vast. The brain is the most complex system in the universe we know about. Even the most complex computer we have isn’t anywhere close. I especially don’t like the term “hard-wired” when we’re talking about the brain, because there’s nothing hard and there are no wires. The properties of a brain are more fluid than those of computers.

Our use of technology always shapes our ability to understand the body, and especially consciousness. Rachel Aviv wrote in one of her pieces in n+1 about how historically metaphors for consciousness have always been determined by the technology of the age. It used to be the telegraph, then the steam engine, and more recently the computer. They’re all only partially useful, if at all. We need a more dynamic model, in the same way that we need a more dynamic model for talking about culture.

I don’t have a good answer to this question. But I do feel like any machine/technology metaphor is going to have problems. I’m actually much more partial to fluid metaphors—rivers, water, current, those are much more reflective of the qualities of both the mind and brain. The flow of neurons seems to me like a fluid process, and the way cultural syndromes flow through a population is a fluid process as well. Part of the problem in the past has been the desire to put discrete, firm borders between one kind of illness and another, when they all have gradations of these fluid qualities.

SFP: A more dynamic model is what you’re offering in the book.

FB: That’s what I’m trying to do. I’ll leave it to people smarter than me to come up with a better metaphor, but I think that idea of a bioloop is pretty accurate and useful. It’s not a vivid metaphor, though, and that might be its fatal flaw. There have been other people in the history of science who have tried to challenge the simple biomedical model. George Engel, the psychiatrist, came up with what he called the biopsychosocial model. It’s one that doesn’t see just a physical to mental flow of things; he tried to take into account psychological and social aspects. But it never really caught on. I think it’s because it’s too messy, too complicated to be a good shorthand. The idea of bioloop is a bit more elegant and has more hope of catching on and being practical.

SFP: Let’s change course a little bit here. One of the threads in the book has to do with you becoming a writer. The book grew out of an article you wrote for Harper’s. I’m curious why you decided to make this your first book and what that process was like.

FB: The Harper’s piece was really a self-contained thing, but there were pieces of it that bothered me—in particular the section where I talked about culture. I felt like there were a lot of unanswered questions there and that those were my real questions. If these syndromes are culture-bound, what does that mean? What are the definitions we’re talking about? I wanted to figure out what it was. I tried to look for a definition of culture for a long time, but I couldn’t figure out specifically what it was or how it worked. I wrote a book proposal after the Harper’s thing came out, but I didn’t have the answers yet. I knew where I wanted to go, but I didn’t know how to get there, and I’m sure that was obvious. So I wasn’t able to sell that book. But it kept bugging me, and I kept working on it.

Then a couple years later I had a kind of breakthrough, where I saw that there was something about one’s life being a story—a chain of causally linked episodes—and that this identity is something we experience as if seen through our friends’ or peers’ eyes. For example, when you do something fun or interesting, you can think of people it would be fun to tell about it; people who would be excited about it. These people would be the audience for the story that that episode is part of. They understand the causal forces leading to and from that episode. They get what it means. They understand what it says about who you are.

Once I started thinking about it that way, and researching that, I pieced together a related essay for Poets & Writers, “The Secret Lives of Stories,” which was along those lines and which was a kind of endpoint for the book, in some ways.

Meanwhile the Harper’s piece kept circulating, so at one point I was contacted by an editor at Melville House asking if I wanted to turn it into a book. By that time, I had a better idea of what I wanted to say and how I wanted to say it. So then I started working on that.

SFP: What are the challenges of working on something longer than a magazine piece?

FB: There were so many moving parts with this book that all had to make sense together. With something shorter, the frame is smaller, so there’s less to manage to make it make sense. Otherwise, it’s the same writing, trying to manage the ideas and storylines and to bring the reader to the point where you want to take them.

SFP: Is it ever hard being aware that the experiences you’re having have while traveling are for the sake of material?

FB: Yes, of course. That’s always an issue with writing nonfiction; there’s always a tension between living the experience and using it for writing. When you write it, it’s always a matter of selection. Nonfiction isn’t just writing down everything that happened. It’s writing down the things that were meaningful. You’re always excluding a lot of irrelevant stuff. In that way, it can feel like you’re sort of falsifying the experience, even though that’s how it works. That’s what writing is. That’s what storytelling is. Writing nonfiction isn’t about what you include, it’s about what you exclude. It’s a version of the storytelling we all do in our lives. We look back on our lives and pick out those episodes that are meaningful and use them to understand who we are, what we’ve gone through and how that event made us into ourselves. Somebody else looking at the same set of events might not pick the same episodes as important or meaningful.

SFP: Has there been any backlash to the book so far?

FB: A lot people assume that when you say something is culture-bound you’re saying it’s not real, or there’s no biology involved, or it doesn’t exist—something like that. But that’s not what I’m saying.

SFP: When you get to that point in the argument and you’re able to come back and say, look at anorexia, look at PMS—that’s a really powerful argument against the idea that our culture is somehow neutral.

FB: Some people just don’t accept these things are culturally related. To me, the one that’s most interesting to me is carpal tunnel syndrome. That seems like a simple mechanical thing, and yet it comes and goes based on the kinds of stories that are floating around, and the kinds of concerns and anxieties people have. It’s a kind of bioattentional looping, where you pay very close attention to your sensations and wind up driving them. It’s one condition where you can see pretty clearly how our narratives become part of this biolooping effect. It’s not saying people aren’t suffering from this or that. But then it goes away.