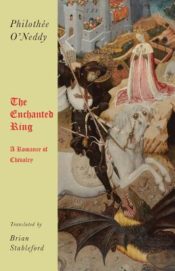

Philothée O’Neddy

Philothée O’Neddy

Translated by Brian Stableford

Snuggly Books ($12)

by Olchar E. Lindsann

Rare would be the reader who recognizes the absurd name Philothée O’Neddy, exclaiming, “O’Neddy in translation? At last!” Ever since his own day he has been not only a footnote in literary history, but a footnote to other footnotes such as Petrus Borel or Gérard de Nerval—his tiny output valued by a miniscule readership rarely touching the anglophone world. For those who know him, and even more for those ready to discover him, this charming tale is a long overdue treat. Though not the ideal introduction to O’Neddy’s work, it is a clever piece of literary subterfuge that yields much when read in light of the author’s context and constraints; sifting through its soil, we find the seeds of avant-gardes to come: Lautréamont, Decadence, Symbolism, and Surrealism.

The Enchanted Ring was originally published serially in 1841, in the popular newspaper La Patrie, under conditions of considerable official and unofficial censorship. It was a kind of trojan horse in which O’Neddy adapted the conventions of the most outwardly conservative of genres to infiltrate the emerging mass market with aesthetically and politically progressive undertones.

Brian Stableford has translated and edited many underground texts over the years, and is one of the few anglophones with an intimate understanding of O’Neddy’s community and its literature. He gives pertinent and insightful observations in the Introduction and notes, although more expansion on the author and the radical nature of his work would better prepare the uninitiated. O’Neddy’s poetry was unpublishably experimental in its day, and he was among the first to call for the merging of art, life, and political action that has characterized the avant-garde since his time; the leaders of the Dada and Surrealist movements cited the Jeunes-France collective that he co-founded as one of their key models. He ceased publishing under the pseudonym O’Neddy after 1833 in the wake of political disenchantment, financial hardship, and unrequited love, and adopted publishable formats in which to smuggle in the themes that his unpublishable verse dealt with more directly. With this context, even the apparently conventional aspects of this novel begin to shake upon their seemingly firm foundations.

O’Neddy rides into this battle against convention protected by the armor of a deep-seated irony that at times merges into pathos. As with many in his generation, cheap Chivalric Romance were the pulp fiction of his youth and guilty pleasure of his adulthood, and he referred to himself on at least one occasion as Don Quixote, a hero of the French Romantics. We must therefore read The Enchanted Ring, and the nostalgia that it invokes so insistently, through the lens of this complex irony, which permeates his lifelong engagement with the chivalric genre. O’Neddy often hides his closest intentions in sarcastic asides, and in parts of the novel (especially in conjunction with his other work, mostly unavailable in English) one can perceive a sketch of a re-invented egalitarian notion of chivalry, in which aristocracy designates allegiance to the sociocultural Ideal, adventure rather than profit motivates and organizes life, and trials and combats are those of amorous relationships or intellectual and creative exploits.

The novel intensifies the chivalric delight in the fantastical and absurd, its deification of love (aptly left untranslated by Stableford as Amour), its utopian aspirations, its sense of adventure and infinite possibility, its values of courage balanced by moderation, its blurring of lines between history and legend, and the hints of nightmare where the seeds of gothic fiction had been planted. It diminishes to a minimum the genre’s inescapable hyper-nationalism, its aristocratic and religious overtones, and its emphasis on combat and machismo.

Anachronisms are tossed about like grenades. The bizarre first chapter features an affable sentient bronze statue throwing sarcastic jabs at the French Academy, and his protagonist is a brazenly fictitious wife of Charlemagne. The marriage is narratively built into the lacunae of history, its secrecy explained away with a vaudevillian grin typical of the Romantic parlor game of “paradoxes” which would evolve into Jarry’s ‘Pataphysics. Such anti-logic intervenes sporadically; after “spoiling” the end of a chapter in its title, he argues that his presumably angry readers “have judged, in accordance with the primordial and chivalric mores of my tale that, in order to be logical, it ought to persevere in its series of consoling and cheerful implausibilities.” The narrator becomes a main character of the book by means of frequent, ironic, and rhetorically elaborate asides, apostrophes, and tangents—sometimes addressing the reader, sometimes directed at representatives of the status quo, and occasionally at the characters themselves, merging and diverging continually with the incidents being spoken, and disclosing O’Neddy as a link between Sterne and Lautréamont.

As a poet ten years earlier, O’Neddy had been a leading representative of “Frenetic” Romanticism, an extremist tendency incorporating gothic fiction, Byronic Romanticism, and leftist politics; it was the subgenre appropriated so radically by Lautréamont twenty years later. In the later chapters, gothic tropes percolate through the medieval tapestry, foreshadowing the Decadent literature of the later 19th century: Pausing in the adventurous clip of questing adventure, the narrator’s gaze catches and lingers rhapsodically on the lineaments of the corpses ringing the dragon’s cave, then on the horse being strangled and devoured by a horde of poisonous serpents.

O’Neddy was a student of medieval hermeticism and Masonic and Egyptian iconography, and combines their logics here with those of popular legend, Voltairian satire, gothic tropes, and onieric imagery (he claimed to sleep in his glasses in order to see his dreams more clearly). The major magical scenes—many of which occur in weird caves, caverns and vaults—evoke more than a touch of what the Surrealists call “convulsive beauty.” All of this is embodied in a prose that is engaging yet unpredictable, and defiantly self-referential. The translation conveys the novel’s charm and eccentricity well, though the heterogeneous aspect of the style could have been pushed more vibrantly: From clause to clause, smooth readability is rejected by means of an eccentric mixture of archaic medieval, poetically proto-Symbolist, jocularly informal, and sarcastically acidic tones, vocabularies, and rhetorical modes generously spiced with neologisms and resurrections of Old and Middle French. Even on the level of syntax, O’Neddy swims in irony, hiding poetry within his prose.

Other continuities with his poetic project also lie underneath the surface. Along with his close collaborator Théophile Gautier, whose career and legacy went on to much better fortune than his own, the atheist O’Neddy had developed a theory and practice of the deification of Art, broadly defined: the societal sublimation of the search for the sacred away from organised religion and dogma, and into cultural activity. By the very fact of its conventional appearance, The Enchanted Ring can be seen as part of O’Neddy’s crafty response to this sense of personal failure and social despair, reminding us again that its irony is more bitter than mocking.

O’Neddy was directly or indirectly engaged with most of the major leftist currents of the early 19th century, and his political stances were influenced by Liberalism, neo-Jacobinism, revolutionary occultism, the predecessors of militant anarchism, and Fourierist and Saint-Simonist socialisms; both of the latter, moreover, were inseperable from Feminism. None of these discourses could be allowed in the mainstream context for which The Enchanted Ring was produced, though they almost break the surface on occasion, such as an acerbic tirade in which O’Neddy compares the institution of marriage to the militarization of the state—then sarcastically apologizes to his readers and loudly disclaims any satirical intentions for the novel.

Nonetheless the book fails in some ways to escape the blind prejudices of its time, most spectacularly in the wholesale adoption of Orientalism that dominates the first chapter and never entirely disappears; in some sense it is the spacial counterpart of the self-conscious nostalgia that is projected onto Europe’s past in the bulk of the novel. The “East” is portrayed in the first chapter, and partly personified for the remainder via the central character of Libania, in the mode of the Thousand-and-One Nights by way of Voltaire (one of O’Neddy’s greatest heroes since childhood). In the idyllic dream-land of “the Orient” we find the typical Romantic fetishization of exotic opulence and pleasurable indolence. We do not, however, find the prevalent associations with “barbarism” or sexual promiscuity, much less any self-conscious racism.

Gender, too, is largely locked into a problematic status by the conventions of the Chivalric Romance genre, and the female protagonist Libania is no exception insofar as she is beautiful, rich, and lacks a male protector. But she also subverts many conventions and is quite explicitly the novel’s strongest character, in every sense of that word. She is an acute scholar, a wise and ethical woman who refuses to reclaim her aristocratic inheritance yet navigates the world with confidence and reliance. While she never picks up a sword to fight, at no point does she desire or need a male protector, and when she accompanies Charlemagne on a perilous quest, she is motivated by her desire to protect him by means of her magic ring; the conventional gender roles have been reversed, and a good deal of ironic humor arises from the King’s self-satisfied assumptions to the contrary.

In many ways Libania manifests the merger that O’Neddy sought of the political principles of the Enlightenment progressive with the utopian fire of the Romantic imagination, and it may not be insignificant that he chooses to embody this ideal in a non-European woman of color. While technically Muslim for most of the novel and technically Christian at the end, her ethos comes off as humanist-pantheist, or atheist; the narrator notes that “the pagan—or, rather, the unbeliever—is a consummate thinker.”

These subtle subversions emerge with more force in the final chapters, in a kind of slow twist of the genre. The serial’s weekly unfolding for readers bears comparison with televised serial dramas today, and once the novel’s reader have been hooked by the earlier idyllic episodes, the subtexts begin to boil up. This twist brings the conflict between O’Neddy’s anti-clericalism and the genre’s Christian roots onto center stage. Religion is not directly attacked—neither the genre nor the newspaper would allow it. Rather, Christianity is treated as simply one genre convention among others, as part of the “local color” of the Middle Ages and not a living ideology. Libania does technically convert to Christianity in the end as a matter of conjugal convenience, satisfying convention, though without any ecstatic experience or fundamental change of perspective implied. But the narrator now becomes more intrusive and opinionated than ever, launching into several bitter invectives and arguments against “the theologians” and clergy over the course of the final two chapters, particularly over matters concerning marriage and love.

The magical ring acts as a test, offering its wearer supreme power, albeit power exerted through the force of love. Only Libania, long before her exposure to Christianity, has the character to wear and wield the ring calmly. On the other hand, the admirable Bishop Turpin—a heroic figure of Chivalric Romance and Charlemagne’s closest advisor until Libania’s advent—is assailed by this temptation in a scene which provides pretext for a long tirade against religious institutions. In this parody of Saint Anthony, the Bishop becomes a symbol of religion as a worldly power, as the devil’s voice tempts him to use the ring’s influence to claim the throne and create an all-powerful theocratic dictatorship. In fact, Bishop Turpin is the only flawed character in the novel, the only one whose actions are explicitly criticized by the voluble narrator, who blames him for his actions and condemns the xenophobic bigotry that motivates them, yet excuses him as deluded by his own ideology and committed to delivering Charlemagne from the world of dream, returning him to the world of action and practicality—the world of prose.

At the remove of more than a century and a half, it is possible that O’Neddy’s disguise may work too well on us, appearing merely as a droll, eccentric tale too trite or idyllic for our age of bigotry, doubt, and impending disaster. Yet it too is the product of a political and personal context in the grip of the forces of reaction, permeated with anxiety and flailing hope, and it proceeds from the pen of one of the most formally and socially progressive poets of his generation, diligently hiding that very fact. If we can read the novel from that shared historical space of cultural crisis and malaise while contemplating the conditions of censorship under which it was written and which are never immune from a return, we can be rewarded with a threefold blessing: an instructive demonstration of literary camouflage, a masterful example of stylistic experimentation and genre-play, and a damned fun fantasy tale.